Trending

Banks are far more exposed to risky real estate loans than you think — thanks to this loophole

Big banks increasingly back debt funds and mortgage REITs

UPDATED, Nov. 6, 4:47 p.m.: Last February, Slate Property Group and GreenOak Real Estate landed a $285 million loan from the Blackstone Group to finance the acquisition and renovation of RiverTower, the enormous Midtown East rental building. It was a bold deal: although the young Manhattan-based Slate has done around $3 billion in deals in recent years, it had never taken on a single transaction close to this size.

In years past, a bank would have been the most likely lender on such a deal. That Slate and GreenOak instead tapped an investment firm for the debt illustrated how real estate finance had changed in the post-2008 era.

But there was a catch not mentioned in news reports at the time. About a month after the loan closed, Blackstone sold the more senior portion of it to the Bank of China, property records show.

Maneuvers like this are rarely publicized. But they are so common that it’s rare to find a real estate loan issued by a non-bank lender like a private debt fund or a commercial mortgage REIT that isn’t ultimately financed at least in part by a conventional bank.

The practice raises questions about whether post-crisis financial regulations carry teeth. After the government had to bail out big banks over soured real estate loans, regulators set out to reduce banks’ exposure to risky commercial mortgages, such as construction or bridge loans. Using tools such as the Dodd-Frank Act and the international Basel III guidelines, regulators made real estate loans less appealing and more expensive for banks. Banks ceded ground to private debt funds and other non-bank lenders. The regulators, it seemed, had succeeded.

But below the surface, banks are far more exposed to risky real estate loans than commonly thought thanks to a skyscraper-sized loophole: Instead of lending to construction projects directly, they increasingly lend to debt funds and mortgage trusts managed by private equity firms, which in turn lend to developers. Slate insists that the RiverTower deal wasn’t particularly risky, that it came with a big equity buffer and that it gets low interest rates on its loans. But in other cases, such as ground-up construction loans, the risk to lenders is more obvious.

“I get a call probably at least once a week from a sub-debt fund for a large project where the dollar amounts are big and they are looking for an A-note lender,” said Jerome Sanzo, head of real estate finance at the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

This means that, ultimately, banks are still bearing some of the risk for construction projects and real estate acquisitions. But since on paper they are merely buying securities or extending supposedly low-risk credit lines to giant fund managers, they can often avoid the stringent limits on how much they can lend against real estate, sources said.

“Banks have become much more sophisticated” in extending credit lines to private funds, including debt funds, said Michael Wolitzer, an attorney at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett. “Now, banks have whole departments focused on it.”

The rise of sideways lending

The commercial and multifamily mortgage market passed the $3 trillion mark for the first time during the first quarter of this year, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

Banks’ share of the market grew by 2.1 percent over the previous quarter to hold 40.5 percent of outstanding CRE debt. REITs grew at a much faster rate during the same period of 8.5 percent to hold 2.4 percent of that market.

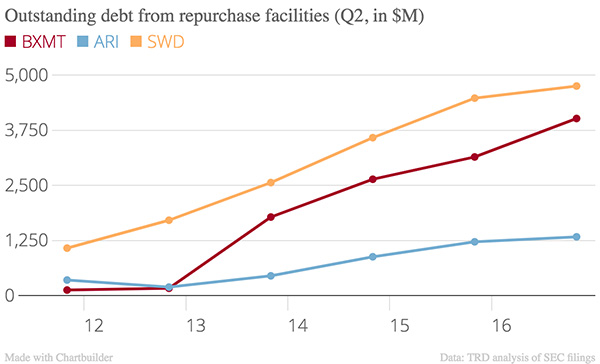

The chart below shows the outstanding debt under bank credit facilities of three major mortgage REITs run by private equity firms: Blackstone Mortgage Trust, Starwood Property Trust and Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance. In the second quarter, these three trusts owed $10.1 billion under so-called repurchase facilities, a type of bank loan secured by the trust’s mortgages. That’s almost a fivefold increase over the second quarter of 2013, when they owed a combined $2.1 billion.

Blackstone Mortgage Trust, Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance and Starwood Property Trust’s outstanding bank debt

A repurchase agreement, or repo, happens when a bank buys a portfolio of loans from a fund or REIT, which then agrees to buy the loans back down the line at an agreed-upon price. The difference between the two purchase prices is effectively the interest that would be paid on a loan.

Individual facilities can be huge. Blackstone Mortgage Trust’s largest facility, provided by Wells Fargo, has a maximum size of $2 billion (of which the REIT had used $1.23 billion as of the second quarter). The REIT had $9.63 billion in loans to real estate projects outstanding in the second quarter and owed $4.01 billion to banks under credit facilities. In other words: these bank deals fund over 40 percent of Blackstone Mortgage Trust’s real estate loans.

Unlike private equity firms’ mortgage REITs, their private debt funds don’t disclose information about bank borrowing. But sources say bank debt is a similarly crucial source of funding here, with one key difference: where mortgage REITs borrow against the loans they issue, debt funds often secure their loans with money pledged by their fund investors under so-called subscription facilities. This means that even though these bank facilities end up funding real estate loans, they aren’t directly secured by them. If the fund defaults on a loan, the bank can get paid back with the money pension funds or family offices committed to the fund instead of foreclosing on the property itself.

“The growth in subscription lines has been substantial in the last couple of years,” said Wolitzer. In the past, these facilities were mainly used as a short term-fix to bridge the time between a fund issuing a real estate loan and the fund drawing down the money from its investors to pay for it. But now, Wolitzer said, they often use them to boost their returns.

Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance’s SEC filings show how the math works. In the second quarter, the mortgage REIT had $3.3 billion in loans to real estate projects outstanding at an average yield of 8.55 percent. It owed $1.33 billion to banks under its repurchase facilities at an average interest rate of 3.53 percent. In other words: Apollo borrowed $1.33 billion from banks at low rates and lent it to developers and real estate investors at a far higher yield. The difference is Apollo’s profit, and likely pushes the percentage return on the REIT’s equity investment well into the double digits because the fund commits less of its own money but still gets a high profit.

Here’s how the magic of leverage works, in simplified terms: Apollo makes $282.1 million per year in interest income on its $3.3 billion loan portfolio. That’s an 8.55-percent yield — good but not quite high enough for a private equity firm. But because it borrows $1.33 billion (at an annual interest rate of $46.9 million, or 3.53 percent) it only actually spends $1.97 billion of its investors’ money. It has to subtract the 3.53-percent interest rate (around $46.9 million) it has to pay to its lenders from its profits, but that still leaves it with a net annual income of $235.2 million — an 11.9-percent return on the $1.97 billion it actually invested.

A low-interest loan “isn’t something our investors are interested in,” said a real estate private equity executive, speaking on condition of anonymity. “They’re interested in the levered return. You have to apply financing to be able to achieve that.”

The A-team

Credit facilities aren’t the only side door banks use to get into the real estate lending game. They also regularly buy the more senior part of a loan from a debt fund. In some cases, funds or mortgage REITs will lend on a property, split the loan into two notes, and sell the more senior one (the so-called A-note) to a bank. Or they might split the loan into a senior and a mezzanine portion, selling the former and keeping the latter.

In April, for example, an affiliate of Brookfield Asset Management loaned DTH Capital and Rose Associates’ $375 million for their office-to-rental conversion at 70 Pine Street. But it only kept the mezzanine portion on its books, selling the senior loan to Bank of China and ING, according to the Commercial Observer. A Brookfield spokesperson did not respond to a request for a comment.

In October, a Blackstone fund issued a $349.5 million construction loan to The Georgetown Company and Bill Ackman to fund the office redevelopment of 787 11th Avenue. It later sold around $275 million of the loan to Goldman Sachs and ICBC, according to property records and sources familiar with the deal. Madison Realty Capital funded Raphael Toledano’s acquisition of an East Village multifamily portfolio with a $125 million loan in 2015 but passed part of the loan on to Signature Bank, property records show. And when Madison recently issued its biggest loan to-date, $300 million in construction financing for Lou Ceruzzi’s condo development at 138 East 50th Street, it refinanced it through an Emigrant Bank subsidiary, records show.

A source close to Blackstone said the private equity firm generally uses credit facilities for its mortgage REIT, while its private debt funds rely mostly on the sale of notes to banks.

The head of a private real estate debt fund manager, speaking on condition of anonymity, said its funds sell about two-thirds of their mortgage loans off to banks.

“It is the rule rather than the exception”, he said.

Selling A-notes is slightly more expensive than using credit lines, he said, but has the advantage of “siloed risk”: the note is secured only by the underlying real estate loan, so in the event of a default, a bank can’t go after a fund’s other assets.

“Everybody wins,” said another debt fund manager: banks get to buy low-risk slices of notes at interest rates that meet their expectations, and fund managers are left with higher returns.

Why banks do it

Regulators set limits on how much real estate lending a bank can do relative to its shareholder equity. If it exceeds these thresholds, it has to hold a larger capital buffer to insure against losses. There are also caps on loan-to-value ratios. Taken together, these rules have made it harder for banks to issue commercial mortgages.

And in early 2015, so-called High Volatility Commercial real Estate rules went into effect as part of the international Basel III framework, requiring banks to hold an extra capital buffer when they issue some construction loans.

A-notes on real estate loans are typically structured as securities, said Peter Weinstock, an attorney at Hunton & Williams. This means banks can generally buy them without having to worry about said concentration thresholds or loan-to-value caps.

“If (banks) pull out of the transitional real estate lending business completely, they will have to find other assets to replace it with,” one fund executive said. “One of the things they’ve done is say ‘we can still participate in the commercial real estate lending business but we’ll either lower our loan-to-cost ratio or we’ll buy A-notes.’”

ICBC’s Sanzo said regulations aren’t the main driver for why banks buy A-notes. These investments offer banks access to a wider range of loans, he argued. And debt funds are likely to return the favor and be more willing to issue mezzanine loans on projects where the bank is a senior lender.

“It’s not necessarily a quid-pro-quo, but there is usually an understanding,” he said.

Credit lines extended to property debt funds aren’t typically viewed by regulators as real estate loans, said Herrick Feinstein’s Richard Morris, provided they don’t overwhelmingly fund construction projects.

Banks that extend these credit lines include Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, UBS, Bank of America, Citibank, JPMorgan Chase, Societe Generale and many more. Sources say several of these big-name banks are also active buyers of A-notes.

It helps that regulators carved out repurchase agreements as an exception to the Volcker Rule of the Dodd-Frank Act, which prohibits banks from sponsoring or investing in private equity funds.

Why this matters

So should there be concern that banks are finding a way around regulations designed to keep them out of risky real estate lending?

TRD asked around among lawmakers and regulators, but mostly encountered shrugs. A spokesperson for Sen. Elizabeth Warren, an outspoken advocate of stricter Wall Street regulations, declined to comment. Barney Frank, a former congressman and co-author of the Dodd-Frank act, said he does not know enough about the specifics of credit lines and A-notes in real estate finance to comment, but said the government should do more to encourage multifamily lending. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York declined to comment. The Treasury Department did not respond to a request for comment.

There’s an argument to be made that banks engaging in such practices is no big deal. Defaults on credit facilities are rare, sources say.

“For smart banks that do it with large, well-capitalized mezzanine lenders, it’s usually a bit safer, Sanzo said. “Unless there’s a huge problem, they’re not going to walk away from their investment.”

Then again, private debt funds and mortgage REITs tend to specialize in high-yield real estate loans. By design, they are riskier. When things go really bad, as they did in 2008, banks can be at risk even if they merely hold the most senior debt.

A real estate debt attorney who spoke on condition of anonymity said banks often underestimate the risk associated with buying A-notes. In theory, the holder of an A-note gets paid off first in the event of a default, while more junior lenders eat losses. But the attorney recalled that during the financial crisis, junior lenders would regularly block repayment until senior lenders paid them off. These extortion tactics meant holders of A-notes still suffered some losses.

Extending credit lines also carries risks. Pre-crisis, Petra Fund REIT, a trust run by Andy Stone’s Petra Capital Management, invested heavily in high-yield mortgages, which it financed by borrowing under low-rate repurchase facilities. As the real estate market collapsed and few people wanted to buy the mortgage-backed securities Petra sold, it suddenly found itself unable to repay its facilities. In October 2010, the REIT and its Cayman-based parent company Petra Offshore Fund LP filed for bankruptcy. According to a filing cited by Law360 at the time, it had $4 million in assets but owed its lenders at least $121 million.

Correction: an earlier version of this post incorrectly noted that Slate Property Group is Brooklyn-based and planned a condo conversion of RiverTower. Although active in Brooklyn, the firm is based in Manhattan and always planned to keep the tower’s units as rentals.