Trending

New York has fined and suspended dozens of real estate agents. Here’s why consumers are left in the dark

DOS' online database is incomplete, difficult to use

Like many New Yorkers who have had bad experiences with real estate agents, Tanya Mejia took to Yelp in September 2014 to give brokerage Chrome Residential a one-star review. “Not only are these guys unprofessional, but they are crooks,” she wrote. “Do yourself a favor and stay clear of this company.”

To retrieve a $2,000 security deposit from her broker, she then went to Small Claims Court and obtained a judgment against Chrome, which the broker refused to pay unless she removed her Yelp review, according to a New York Department of State investigation. Mejia then filed a consumer complaint with the DOS, and finally, more than two years after the initial incident, an administrative law judge revoked the real estate broker’s license in September 2016.

But as far as the state’s public database of licensing decisions is concerned, this never happened. A search for the agent’s name (“Jacob Benchlouch”) only turns up two duplicate files for an earlier dismissed complaint, omitting any record that he was sanctioned for “engaging in deceptive acts and practices.” (Benchlouch could not be reached for comment and Chrome Residential is no longer in operation.)

To protect the interests of New York’s consumers, the DOS’ Division of Licensing Services regulates a number of professions, including real estate brokers and salespersons, by handing down fines, suspensions and revoking licenses as it deems necessary. But because the agency uses rudimentary public disclosure tools that are difficult to navigate and often incomplete, it is difficult for consumers to identify sanctioned brokers, leaving open the possibility that they will harm another consumer.

“The database needs to be dramatically improved, and unfortunately this is a problem that is all too common and easily fixed,” said Alex Camarda, a senior policy advisor at Reinvent Albany, a government watchdog group. “Many state databases lack the basic fundamental qualities of good open data practice.”

Using a collection of court decisions from an archive maintained by the New York State Association of Realtors (NYSAR), an analysis by The Real Deal identified 23 real estate licensing decisions issued over the past 10 years that are missing from the state’s own online records – including the one against Chrome Residential. On average, the DOS makes about 40 real estate licensing decisions per year according to the analysis of its database, making this a significant amount of missing files.

“It’s obviously troubling when you have administrative hearing records that should be in the database but are not, since users are not gaining a full picture of government actions,” said Camarda.

Because NYSAR’s archive does not contain all real estate-related decisions either – more than 80 decisions which can be found on the DOS website between 2010 and 2017 are not recorded by NYSAR – it is possible that yet more decisions can’t be found anywhere online.

In addition to decisions made by an administrative law judge, the DOS also maintains records of consent orders – agreements between a company or an agent and the state in which they admit wrongdoing and usually pay a fine. While the search engine can find decision files dating back to the early 1990s, it can only find consent orders dating from 2014 to the present – despite the fact that the DOS was able to provide TRD with hundreds of earlier consent orders as part of an investigation in 2013.

Depending on the violation, consent order payments can range from one hundred dollars to tens of thousands of dollars. For example, one agent – Dimitri Kirsheh from Staten Island – in March 2009 agreed to pay $25,000 in restitution to a client after failing to maintain an escrow account. Another licensed broker, Pedro Tronilo, now the owner of an Exit Realty Group franchise in Queens, agreed to pay a $10,000 fine in February 2010 when an audit found that he had acted as both a mortgage and real estate broker on multiple deals without proper disclosure. Neither of these cases can be found on the database because they occurred before 2014. Kirsheh confirmed the facts of the case, while Tronilo did not respond to requests for comment.

According to DOS documents dating from between 2009 and 2011, more than a dozen other cases involving currently-active brokerages resulted in consent orders and fines of $2,000 or more – none of which can be found online.

A spokesperson for the DOS said no documents have been intentionally excluded from the database. Nevertheless, the department acknowledges the incompleteness of the database and the limitations of its search tools.

“The decisions and orders found on the site are for a matter of convenience and do not represent the entire catalog of agency precedent. They are provided as a tool for those wishing to view sample determinations and orders,” said DOS communications director Lee Park in an email. “As with any other publicly available records, the Department of State’s library of decisions and orders can be obtained by filing a request pursuant to the Freedom of Information Law.”

Even the files that are not missing are presented in an unwieldy manner for public consumption.

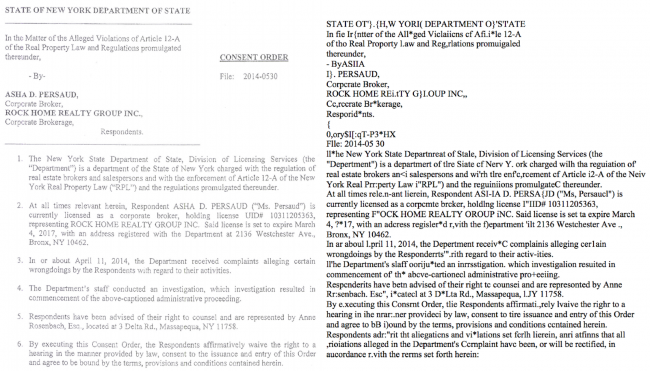

One basic tenet of “good open data practice” is to present text in a way that a search engine can actually read. The DOS stores all consent orders as scanned images whose contents cannot be searched. Out of a total of 194 consent orders pertaining to real estate complaints, only six come with machine-searchable text, and even that text is severely garbled.

Figure 1. On the left: scanned image; on the right – “searchable” machine-extracted text.

Further, decisions pertaining to real estate cases are lumped in with decisions for other licensed industries like security guards, barbers, and cosmetologists, and decisions regarding complaints are not filed separately from license applications and appeals. This means that there is no straightforward way to limit a search to only real estate complaints, other than searching for various keywords – an approach that the website openly admits is not fully reliable.

“Please note that while using the license type names listed above should return most results for that discipline, there is no guarantee that all results will be found. For example, some decisions may have used the term barbering instead of barber; salesman instead of salesperson, waxing instead of cosmetology, etc.” the website states under “Search Tips.”

Given the unreliability of the DOS database, NYSAR’s legal team has taken a multi-pronged approach to getting decision documents, which it provides on its website as a legal reference for its members. “We have received copies from the DOS directly, the DOS website and sometimes copies of decisions are forwarded by various legal counsel to NYSAR general counsel,” a NYSAR spokesperson said.

A spokesperson for the Real Estate Board of New York declined to comment on the DOS’ incomplete database and the impact it might have on the industry.

According to a DOS spokesperson, the department is currently in the process of redesigning its entire website. This would be a timely update, since the Google Search Appliance that currently powers the DOS’s search tool will become defunct in early 2019, rendering it unusable.

This story is the first in a series from TRD that will examine various aspects of the regulation of real estate licensees in New York, by the Department of State and other agencies. Check back for more.