Trending

Big Real Estate facing new limits on NY state campaign contributions

The new limits will go into effect after the 2022 election, unless lawmakers call a special session before December 22

New York is about to slash the amounts that real estate donors and other large contributors can give to candidates for governor and other statewide offices.

The state’s Public Finance Commission released a set of recommendations Sunday to lower the limit on contributions to statewide candidates to a quarter of the current ceiling. The commission recommended a limit for statewide candidates of $18,000, down from $70,000, between primary and general elections.

For candidates for state Senate, the contribution limit will be $10,000, down from $19,000, and for Assembly campaigns, it will be $6,000, down from $9,000. The new limits will take effect after the November 2022 election, meaning neither the upcoming 2020 state legislative races nor the 2022 elections for all state offices will be subject to them. The recommendations placed no maximum on contributions to party committees, which are already seen as a loophole to donation limits.

The commission’s recommendations will become law unless the state legislature convenes before Dec. 22 — which observers say is unlikely. Yesterday, Gov. Andrew Cuomo dared lawmakers to call a special session if they don’t like the proposal.

“If you’re not happy with it then you can come back in a special session,” Cuomo said during a press conference Tuesday afternoon, according to news reports. “That’s [legislators’] choice now. If they don’t like the plan they should come back into special session and reform it.”

Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie was noncommittal on bringing legislators back to the capital during the holiday season.

“We’ll just see what happens,” he said to reporters in Albany on Tuesday.

Members of the public finance commission were appointed in July by Heastie, Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins. One of Heastie’s appointees, Rosanna Vargas, was formerly a lobbyist for real estate firm Azimuth Development Group, and Acadia Sherman Avenue, a role that has raised eyebrows in the past.

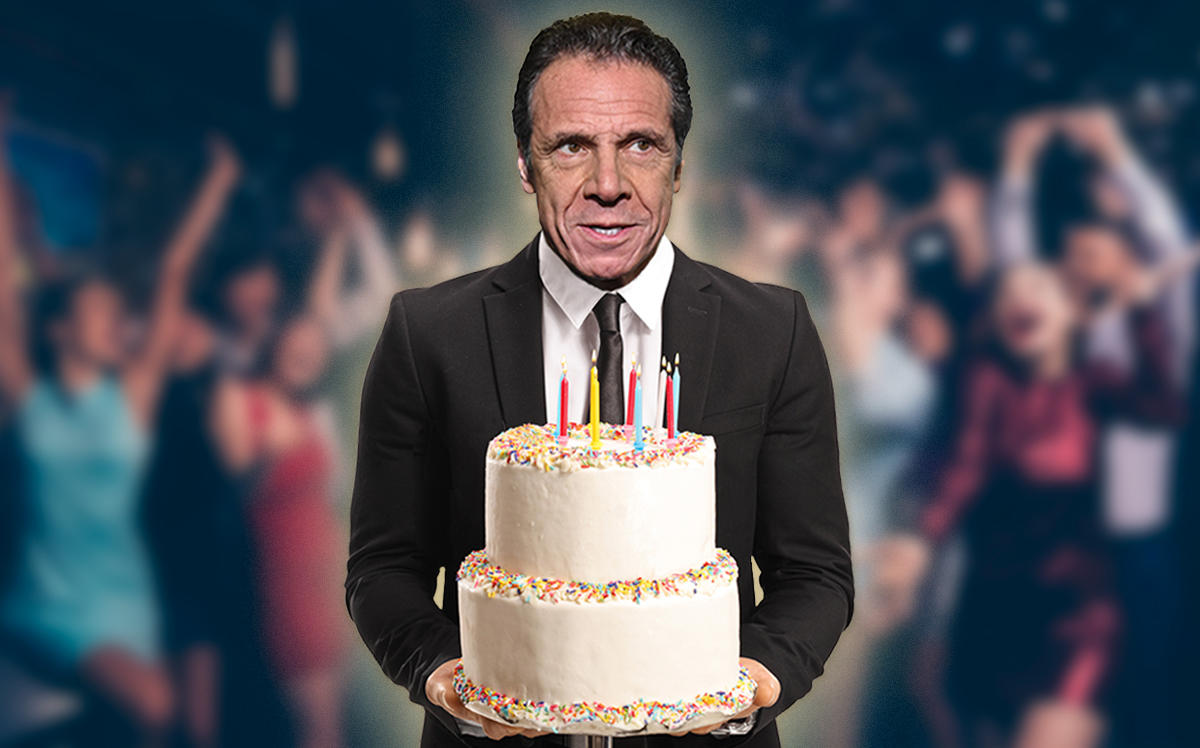

The Public Finance Commission dropped its report just a few days before one of the biggest fundraising events on New York City’s social calendar — Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s birthday party Wednesday night. Individuals were asked to donate $5,000 to attend the fête at Essex House at Central Park South.

But according to one real estate lobbyist, the Real Estate Board of New York planned to skip the governor’s party. One multifamily real estate lobbyist had no plans to attend, and the head of another landlord trade association was not invited. According to another industry source, the list of real estate figures who planned to attend could be counted on one hand.

“I’m willing to bet the only real estate people who will go are hard-core, longtime loyalists,” the source said Wednesday evening before the party. “Since the industry leadership is so pissed at him for the rent laws.”

REBNY declined to comment.

Cuomo, according to eyewitness accounts, sneaked into his birthday party through a side entrance accompanied by a police escort. The main entrance to the hotel was blocked by protesters seeking to present the governor with a birthday cake decorated to say, “#MakeBillionairesPay.”

The commission’s recommendations also up the requirements for candidates seeking statewide office on an independent party line — such as the progressive Working Family Parties, which endorsed Cynthia Nixon in her failed bid to unseat Cuomo. Those candidates will also have to obtain 500 signatures in at least half of New York’s congressional districts.

“It will make it harder for [donors] to drive money toward particular candidates,” said Cozen O’Connor’s Kenneth Fisher. “It’s just another step toward the decentralization of politics, and will lead to more real estate players funding independent campaigns.” Independent campaigns can support an individual candidate but not coordinate with a candidate’s campaign.

The real estate industry has long been accustomed to giving sizable donations to politicians, and these limits will change their ability to do so.

“Real estate traditionally has been some of the biggest campaign contributors in Albany, often giving large contributions through limited liability companies, but they are far from the only ones,” said Alex Camarda, senior policy advisor at Reinvent Albany, a good-government group that lobbies for stricter limits on campaign gifts. “We’re trying to amplify the voice of small voters and getting people to raise money from people in their district and state.”

The new limits, while not directed at contributions from any single industry, may just be the latest reason for the real estate industry to adopt strategies for making their case to lawmakers beyond writing checks.

“The real estate industry will be looking to make their case in Albany to elected officials, and already there is a good number of people who are refusing to take real estate money,” said longtime political strategist George Arzt. “So I think they have to sit down with the legislators and make their point— that they’re not the villains here.”