Trending

How the coronavirus crisis is gutting real estate

A deadly pandemic, sweeping lockdowns and an imminent economic crisis shake the foundations of the real estate industry

In just three months, the coronavirus ravaging the globe has infected at least 750,000 people and killed nearly 37,000. And those are just the confirmed numbers.

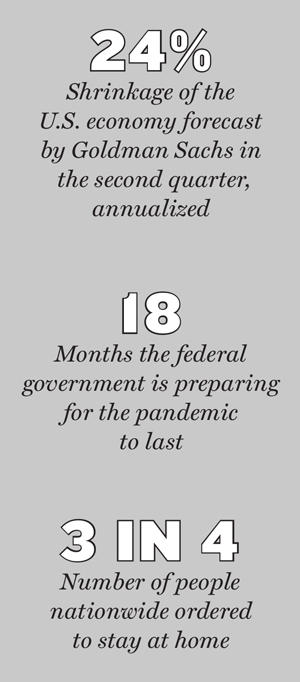

The pandemic has also stopped the longest-running bull market in history, put the world’s biggest economies into intensive care and become a mortal threat to storied companies. In less than a month, the Dow Jones Industrial Average sank 35 percent before Congress passed a $2 trillion stimulus package, the largest ever.

The full impact of the outbreak is impossible to calculate. But the devastating effects are already clear — especially in the United States and in New York City, which alone generates $1.7 trillion of economic activity — 8 percent of America’s total.

By March 31, the U.S. had 163,539 cases, more than any other nation. Nearly half were in New York state, and most of those were in the city, which had more than 40,900 confirmed cases.

“It’s amazing and scary when you see the lines of people trying to get into emergency rooms just to be tested,” RXR Realty CEO Scott Rechler said during an interview on TRD Talks Live, a series of webinars prompted by the coronavirus panic.

“Now is not the time to try to make this perfect,” Rechler said as a debate raged over the details of Washington’s intervention. “We need to get liquidity in the system and make sure that people don’t lose jobs.”

Read more

What started as a marginal concern for New York’s real estate industry in February now poses an existential threat to commercial landlords, office and retail tenants, hoteliers, a growing number of real estate lenders and a brokerage industry built on face-to-face dealings.

Swanky shopping districts are boarded up, once-bustling office skyscrapers stand empty and even the iconic Plaza Hotel is closed.

Nearly everyone across the city is holed up in their homes, and all entertainment venues and “nonessential” stores are shuttered. The real estate industry is scrambling to adapt as landlords, developers, investors and others wait to see if the stimulus package can save them from a massing tidal wave of red ink.

Donna Olshan, who has been running her own Manhattan-based residential brokerage since 1980, echoed the assessment of many as she described the sense of a world-changing cataclysm.

“I have been in business for 40 years,” she said, “and this looks like a cross between 9/11 and 2008.”

Economic earthquake

As the virus engulfed the globe, the world’s markets went into a free fall, even dragging down most real estate investment trusts, which are typically safe havens during volatility because their revenue streams are based on long-term leases.

Initially, the hardest hit were publicly traded companies that have exposure to Asian hotels. But the contagion soon spread to other real estate stalwarts such as the country’s largest mall REIT, Simon Property Group, and even diversified giant Brookfield Property Partners, which saw its share price fall from $17 in early March to $8 by month’s end.

Repeated interventions by the Federal Reserve have failed to slow real estate’s meltdown. The central bank slashed interest rates to nearly zero, but its purchases of commercial mortgage-backed securities and investment-grade bonds were too narrow to include most real estate firms that needed help. Several insiders say the worst is yet to come.

Trading in securitized commercial mortgages ground to a halt as investors balked at pricing the risk. “The CMBS market is shut down,” one mortgage broker told The Real Deal in mid-March.

Just days before TRD’s April issue went to print, Congress passed its $2 trillion stimulus, which includes direct payments to most Americans and even a $170 billion windfall for real estate investors in the form of increased depreciation write-downs.

Just days before TRD’s April issue went to print, Congress passed its $2 trillion stimulus, which includes direct payments to most Americans and even a $170 billion windfall for real estate investors in the form of increased depreciation write-downs.

But while the unprecedented rescue package — officially called the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (or CARES) Act — earmarks aid for several troubled sectors, such as airlines and retailers, it largely passes over the real estate industry’s backbone.

“There’s nothing really in the CARES Act that provides for landlords,” said Alan Hammer, an attorney at New Jersey-based Brach Eichler.

Ripple effects

The coronavirus pandemic and economic fallout have shaken every facet of real estate.

The first sector to take ill was the hospitality industry, which was already weakened by oversupply and debt. With occupancy rates plunging, industry leaders on March 17 appealed to America’s hotelier president for a $150 billion taxpayer bailout.

Even before states imposed lockdowns, major retailers including Macy’s, Apple, Nike and Nordstrom announced plans to close stores for about two weeks. But New York state’s closure of “nonessential” businesses could be extended indefinitely.

Shuttered to customers, some retailers warned their landlords they may not pay rent on April 1. And the day after hotel firms begged for a federal backstop, the International Council of Shopping Centers also asked for government support.

Office towers likewise began emptying as companies told employees to work from home. Then, Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s order for all nonessential workers to stay home completed the evacuation. Between March 9 and March 23, when the order took effect, physical occupancy rates for commercial office space went from 90 percent to 2.7 percent, according to the Real Estate Board of New York (see related story on page 30).

Because many workers in the city can’t telecommute, the order triggered mass unemployment and a looming rent crisis. On March 15, the state barred evictions — both residential and commercial — indefinitely.

And while the relationship between tenants and landlords is coming unmoored, the work of brokers is already swept out to sea. Open houses are history, and even individual showings ended after the governor told real estate agents to stop. With the brokerage business in an induced coma, REBNY and StreetEasy agreed to remove the number of days on the market from listings.

The pandemic is also incapacitating construction, though Cuomo initially granted the industry a blanket exemption to his stay-home order. But then LaGuardia’s $8 billion renovation and Moynihan Train Hall’s $1.6 billion redevelopment both stopped when workers tested positive for coronavirus, and on March 27, Cuomo halted most kinds of projects.

The coronavirus had already blocked others from even gaining approval after the city put the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure on indefinite hold, stranding 119 active ULURP applications, 45 of which had already started the seven-month clock, a TRD analysis found.

Moreover, projects permitted to go forward may not be able to, as the pandemic has disrupted global supply chains for building materials such as finishings from China and stone from Italy. Clay Edwards, executive vice president and partner at Chicago-based construction firm Skender, said he expects more problems as the crisis drags on.

“I don’t think we’ve seen the worst of it by any means,” he said.

Lockdown, hand up

Growing fears and Cuomo’s lockdown have already cost people in an estimated one-third of New York City households their jobs, while restaurants across the city have lost at least $2 billion in sales, according to recent surveys.

That comes on top of huge business losses nationwide, with the Fed now projecting that the coronavirus could drive unemployment as high as 32 percent.

The federal stimulus offers most Americans a $1,200 check, but that’s little help to retailers — or their landlords, investors and lenders — when people can’t or won’t go shopping. Nor would it come close to covering the $2,152 median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the city.

For its part, New York City will provide interest-free loans of up to $75,000 to businesses with fewer than 100 employees if they can demonstrate that sales fell by 25 percent or more.

For its part, New York City will provide interest-free loans of up to $75,000 to businesses with fewer than 100 employees if they can demonstrate that sales fell by 25 percent or more.

State Sen. Michael Gianaris has a bolder idea that would shift the burden to lenders rather than the city. His bill would suspend rents for 90 days for small-business and residential tenants hurt by the coronavirus — and forgive mortgage payments for landlords facing hardship as a result.

The logic is to shift the burden from individuals and small businesses to firms with the clout to pass the buck to Uncle Sam, said Gianaris, predicting the banks are the “best-positioned to seek federal relief.”

But if loan forbearance is widely adopted and payments are pushed back six months or more, mortgage lenders could be on the hook for up to $100 billion, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Mortgage servicers are required to continue paying interest even when the borrower is in arrears.

“It’s going to be a liquidity tsunami,” Jay Bray, CEO of mortgage lender Mr. Cooper, told the Wall Street Journal.

Lingering symptoms

It’s impossible to foresee how long the pandemic, the lockdowns or the resulting economic turmoil will last. But even after business resumes, the impacts of the crisis will endure.

Retailers and their landlords fear their quarantined customers will get so used to buying everything online that they won’t return even when it’s safe. And hoteliers worry that a surge in telecommuting and virtual meetings will curb business travel and conferences.

But for all the comparisons of this crisis to 9/11 and the Great Recession, if those catastrophes proved anything, it’s that New York real estate is resilient.

Firms that quickly drew down credit lines in anticipation of a credit crunch like that of 2008 have war chests of capital that could be deployed to acquire floundering rivals. Virtual brokerages and proptech firms born to do business at arm’s length may take advantage of the unprecedented disruption. And there are always funds hoarding dry powder, ready to swoop in on assets in distress.

It’s a moment for survival of the fittest — or at least the most liquid, according to attorney Evan Hudson of Stroock & Stroock & Lavan. “This is a shakeout,” he said, “and the winners are going to be the REITs and the private buyers that already have liquidity.”

But veteran developer Steve Witkoff cautioned that this crisis is unlike anything the modern business world has faced.

“This is the first time ever that we’ve had, at the same time, a chain of a supply shock to the system and a demand shock to the system,” he said in a TRD Talks Live webinar.

“The medicine right now is that we’ve got to shut down demand,” Witkoff added, referring to closed stores, canceled events and self-isolation to quell the outbreak. “That means that the cure may be worse than the actual disease.”

—Reporting by Rich Bockmann, Mary Diduch, Kathryn Brenzel, Erin Hudson, Eddie Small, Georgia Kromrei, Sylvia Varnham O’Regan and Kevin Sun