Trending

A tale of two markets: Some CMBS players see huge losses, others opportunity

When investment giants like Starwood and Brookfield hand the keys back to their lenders, it’s a sign of problems yet to come.

Nobody knows how to sniff out distress like Barry Sternlicht.

In the early ‘90s, in the thick of the savings and loans crisis, his company Starwood Capital Group scooped up real estate loans for pennies on the dollar. And after snapping up distressed debt from Miami to Los Angeles during the financial collapse of 2008, Starwood became one of the largest real estate investors in the country.

Sternlicht knows how to make money when others are losing it. So when his firm hands the keys over to one of its lenders on a nearly 1 million-square-foot mall outside of Chicago, it’s a beacon of foreclosures and distress yet to come.

Investment giants like Starwood, along with Brookfield Property Partners and Bahraini-based Investcorp, have sought to turn over hotel and retail properties tied to securitized commercial mortgages as the pandemic continues to batter those markets.

Across the U.S., major borrowers are seeking to let go of at least 100 assets in the commercial mortgage-backed securities market with an outstanding balance of nearly $4 billion, according to data provider Trepp.

The process — commonly referred to as “jingle mail” to signify the keys being mailed back to lenders and special servicers — could become more common. And as forbearances grow, more banks and other CMBS servicers are going to be faced with the difficult decision of foreclosing or making serious loan modifications.

“We see a mess coming down the pipe,” said Shlomo Chopp, managing director of New York-based Case Property Services, a firm that focuses on CMBS debt restructuring. “Whether it’s a mess for the borrower, or the lender and bondholder, it’s going to be a mess for somebody.”

But despite a litany of problems with overleveraged and poorly timed CMBS deals in the past decade, some borrowers are still turning to the market for financing. Investors, in search of greater yield, are also looking to buy some of the riskier portions of securitized commercial debt.

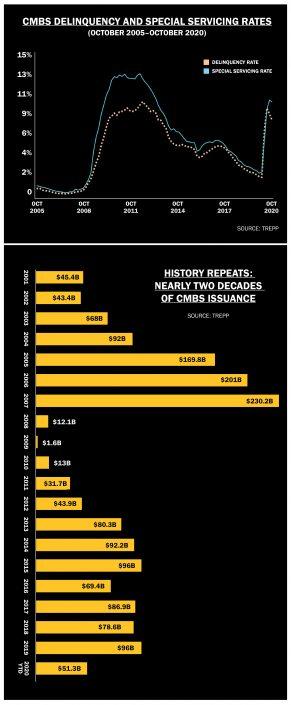

Year to date, CMBS issuance has amounted to just over $51 billion in 2020, about half of the total in 2019, according to Trepp. The market — which peaked at $230 billion in 2007 — is a far cry from its much frothier days. And while hotel and retail borrowers will be seeing fewer securitized commercial loans going forward, industry experts say demand for CMBS financing on industrial, multifamily and office properties could rise in the near future.

“If your property qualifies for CMBS it is always going to be your best maximum leverage, non-recourse fixed-rate option,” said David Pascale, a senior vice president at the advisory firm George Smith Partners who arranges debt and equity for commercial real estate borrowers and lenders.

Death of a mall

When Starwood purchased the Louis Joliet Mall from the Westfield Group in 2012, the property had an occupancy rate close to 95 percent and an appraised value of more than $130 million. Since then, two of the mall’s main anchor tenants have departed: Carson’s in 2018 and Sears in 2019.

Starwood, which lost control of a separate U.S. mall portfolio in recent months, stopped making debt payments on the Chicago metro area property in March. The company is now delinquent on a $85 million CMBS loan secured by the mall. And while the asset’s overall value has not been reassessed since Starwood’s acquisition, it is likely worth far less than its 2012 appraisal.

Other institutional giants are making similar moves. Investcorp stopped making payments on a $65 million loan tied to a struggling indoor shopping center just south of Miami, which is now being shopped. And in Florence, Kentucky, Brookfield is seeking to ditch a regional mall backing a $90 million CMBS loan to avoid foreclosure, according to Trepp.

We see a mess coming down the pipe. Whether it’s a mess for the borrower, or for the lender and bondholder, it’s going to be a mess for somebody. — Shlomo Chopp, Case Property Services

Even among the country’s largest investment firms, CMBS debt presents a number of unique challenges for borrowers. That includes fixed obligations to bondholders that often call for highly complex negotiations when it comes to loan workouts.

Unlike with conventional loans that can often be restructured with a call to the bank, CMBS borrowers have to go through a lengthy process with their special servicers before the debt can be modified. And in order for major loan modifications to go through, bondholders must approve the changes through a trust. Sometimes, that entire process can take borrowers up to a year or more.

But as special servicing fees rise, a wave of foreclosures could be coming soon — especially on properties where the equity is now worth less than the debt.

“Properties are going to be liquidated faster than people expect,” said Dan McNamara, a principal at the asset management firm MP Securitized Credit Partners, who has short and long positions in some CMBS indexes. “Special servicers can’t take the keys back on everything and sit on these properties, it’s not in the best interest of the trust.”

For borrowers, one of the biggest challenges with CMBS debt is that once a loan reaches special servicing it cannot be refinanced, which means equity cannot be taken out of the property to pay down debt.

“If the borrower recently cashed out with a refinancing, they will be more likely to hand [the property] back to the lender,” said Suzanne Amaducci-Adams, a partner and head of real estate at the Miami-based law firm Bilzin Sumberg.

Owners of suburban malls have been among the hardest hit during the pandemic.

Outside of Minneapolis, for example, a $63 million CMBS loan secured by half of the 1 million-square-foot Burnsville Center hit the auction block this month. The chunk of the mall backing the debt was last valued at just over $137 million in 2010. But when the loan was sold off to investors, it yielded $17 million, marking a nearly 85 percent drop in the value of the collateral.

Of the 100 CMBS loans that could be turned over to lenders from March to October, the vast majority are backed by hotel and retail properties, according to Trepp. Only one loan was backed by an office building, while another was backed by a low-rise multifamily asset. No loans were backed by an industrial property.

Special servicers can’t take the keys back on everything and sit on these properties, it’s not in the best interest of the trust. — Dan McNamara, MP Securitized Credit Partners

One of these distressed deals includes a $13.1 million loan backed by the Eastgate Holiday Inn in Cincinnati that is now going through foreclosure proceedings.

In the first half of 2020, the loan had a debt service coverage ratio — a measure of the property’s ability to cover its debt payments — of negative 0.38, with an occupancy rate of just 33 percent. Last year, the loan’s debt service was just under 1.4 while its occupancy was 67 percent.

Learning curves

Of course, there are many properties that are being successfully worked out between borrowers and servicers, especially for borrowers with deep pockets.

In September, Jeffrey Soffer’s Fontainebleau Miami Beach resort renegotiated its $975 million CMBS loan with its servicer KeyBank and exited special servicing. Part of the agreement allowed the Fontainebleau to defer monthly furniture, fixtures and equipment reserve payments to next year.

“We’re fortunate to be located in South Florida, which is on the better end of the recovery curve,” Brett Mufson, president of Fontainebleau Development, told The Real Deal last month.

At the same time, location has also become a telling sign of whether a loan is heading to special servicing. In Miami, where Covid restrictions have been largely lifted, delinquency rates for CMBS loans tied to hotel and retail properties rose to about 8.5 percent and 7.4 percent in October, respectively, according to Trepp. That’s up from zero percent and 1 percent in March.

In New York, meanwhile, delinquency rates for securitized loans on retail and hotel properties skyrocketed to 12 percent and 30 percent in the same period, both up from less than 5 percent in March.

And while location matters, so does property type.

Hotel properties had the highest delinquency rate in October at 17.5 percent, while retail properties were at 11.3 percent.

Nationally, delinquency rates for asset classes outside of lodging and retail remain relatively low. In October, rates rose to 1.86 percent with office properties, 0.72 percent with multifamily and 0.53 percent with industrial, according to Fitch Ratings.

The total CMBS delinquency rate is still far below its peak of about 9 percent in July 2011, following the Great Recession. This October, the rate rose to 4.85 percent, according to data from Fitch.

Plotting a plan B

Even amid rising delinquencies and foreclosures and dwindling CMBS issuance, there are still deals getting done.

CMBS deals, typically structured as 10-year loans, still offer some of the best interest rates for borrowers and the vast majority are non-recourse, which means bondholders and lenders can only go after the collateral in the event of default.

The market is “very active right now for the right deals,” George Smith Partners’ Pascale maintained.

Office buildings, many with long-term leases still in place, have accounted for 44 percent of new securitized commercial mortgages since the pandemic began, according to Kroll. Those transactions include Brookfield and Qatar Investment Authority’s One Manhattan West office complex in Hudson Yards, which was refinanced with a nearly $1.5 billion CMBS loan this summer. In a telling sign of bondholder interest: The One Manhattan West deal was oversubscribed by investors.

And in Silicon Valley, San Francisco-based Sansome Partners and an affiliate of Hunter Properties secured a $155 million CMBS loan in August to refinance part of a suburban office complex that’s leased to the digital media company Roku.

Institutional investors such as KKR and Oxford Properties have also targeted the CMBS market in recent months. Specifically, firms are looking to buy up B-pieces, one of the riskiest slices of newly issued loans since those bondholders get paid back farther down the line.

In October, the return investors seek to hold on an index of BB-rated CMBS bonds over 10-year U.S. Treasuries — commonly referred to as the spread — rose to its widest levels since the financial crisis, according to Trepp.

In July, KKR closed a $950 million fund committed to snapping up to B-pieces of newly issued CMBS deals. The global investment firm is specifically targeting loans that banks are trying to get off their balance sheets.

Under the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, lenders were required to have some “skin in the game” when originating CMBS loans. The goal was to prevent lenders from underwriting shoddy loans and then immediately rushing them off their balance sheets. An exception allowed lenders to sell these loans to private investors, which then bear the risk if the loans default.

In the case of KKR, the private equity firm is “re-underwriting” the deals and inspecting each site, according to Matt Salem, head of real estate credit for KKR.

“Our thesis, dating back to our first fund in the beginning of 2017, was that the new risk retention rules would lead to higher quality CMBS loans,” Salem told TRD in an email. The originators of the commercial mortgages, which are largely banks, do not want to keep all of “the required risk retention” on their books, he argued.

Opportunities could become even more plentiful as banks — which have deferred many of their loans — face write-downs and are forced to sell off their debt.

That wave of distress has yet to come. But, in the meantime, investors and vulture funds will be waiting to pick up the pieces.