Trending

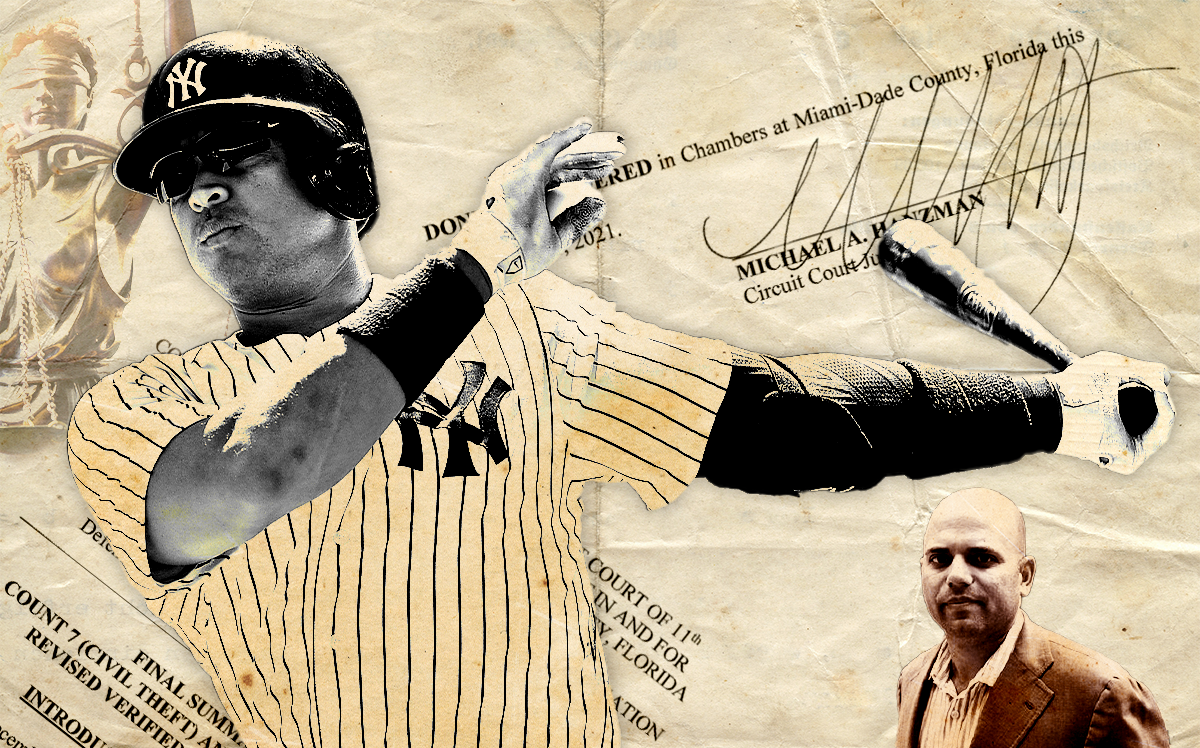

Big win: A-Rod prevails on civil RICO, theft claims tied to multifamily empire

Trial on remaining claims starts Nov. 15

Alexander Rodriguez is so far hitting it out of the ballpark in a suit filed by his ex-brother-in-law, Constantine Scurtis, over their unraveled real estate empire.

A Miami judge on Wednesday struck Scurtis’ racketeering and theft counts, both civil claims, against A-Rod, saving the former baseball slugger from tens of millions of dollars in damages.

The ruling came on the heels of the judge dismissing, in September, 13 lawsuits Scurtis filed against Rodriguez . (These suits were separate from Scurtis’ main lawsuit but still were tied to the real estate venture.)

Still, some claims from the 59-count total suit remain, and a jury trial is scheduled in Miami later this month.

Rodriguez married Scurtis’ sister Cynthia Scurtis in 2002, and shortly afterwards partnered with Constantine Scurtis on real estate purchases. The duo amassed roughly 5,000 apartments, mostly Class C units, in Florida, Texas, Mississippi, Indiana and Oklahoma for $300 million, according to court filings. They also bought an assemblage in Miami’s trendy Edgewater neighborhood that they dubbed “Promised Land,” where they envisioned a 782-unit luxury condominium.

When Rodriguez and Cynthia Scurtis divorced in 2008, the real estate partnership also broke up, as Constantine Scurtis was removed from the ventures, according to the judge’s ruling.

Scurtis first sued Rodriguez in 2014, alleging he was pushed out and shortchanged on his earnings. Rodriguez responded with a countersuit against Scurtis alleging he dipped into the partnership’s coffers to the tune of $1.4 million. Rodriguez claimed in court that Scurtis’ suit was a way of trying to extort and harass the ex-Yankee and wiggle out of refunding money Scurtis took.

In the ensuing years, Scurtis tweaked his complaint four times to beef up claims, at one point saying he was owed $2.2 million in property sale profits and $8 million pursuant to an agreement that he would be paid a 3 percent acquisition fee.

He added the racketeering and theft counts in his most recent amended suit, filed in January.

In his ruling, Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Michael Hanzman said these counts were added “for no purpose other than to embarrass Rodriguez, generate sensationalized press, and increase settlement leverage.”

Hanzman went on to call some of Scurtis’ claims “completely fanciful,” “self-serving” and “anemic.”

Before the kerfuffle erupted, Rodriguez and Scurtis built up their empire by buying each property using a different affiliate.

Rodriguez, as the well-heeled baseball player who was with the Yankees at the time, bankrolled the venture and held a 95 percent stake in each buying entity, according to the judge’s ruling. Scurtis, as the real estate savvy partner, provided the know-how by picking the properties they bought. He held a 5 percent stake in each entity.

The general partner of each buying entity was a limited liability company called ACREI – standing for Alex Constantine Real Estate Investments – and controlled by Scurtis, according to Hanzman’s ruling. Controlling the general partner gave Scurtis legal control over the buying entities.

This structure changed in 2005 with essentially Newport Property Apartment Ventures Inc. replacing ACREI, putting Rodriguez, instead of Scurtis, in control of the new general partner, according to the judge’s ruling. The rearrangement was made because the venture was growing and the duo created a new entity to serve as loan guarantor, as a way for Rodriguez and Scurtis to buffer themselves from personal liability on debt, the judge wrote.

The partnership continued to amass real estate under the new structure.

Although Scurtis signed off on this transfer of control, he later claimed it was a fraudulent reassignment and that he did not knowingly sign off, Hanzman wrote in his ruling.

Scurtis alleged that his interest in the venture was stolen from him behind his back, and that he thought he continued to control the general partner – a claim the judge said “reeks of afterthought and strains credulity.”

In fact, Hanzman wrote, there was nothing odd about Rodriguez taking over legal control of the venture, as he was, after all, the majority owner of the business.

For a time, Scurtis himself had represented to lenders that the business had a new general partner, Hanzman wrote. And when his ties with the venture were severed, Scurtis sent messages to employees telling them he no longer worked for the partnership.

Scurtis has since become the head of Texas-based multifamily investor Lynd’s acquisition arm.

Scurtis also alleged that the partnership made tax filings that showed he was paid, even though he was not. What really happened was that Scurtis took out loans from the partnerships, Hanzman wrote. When the debt became due, the partnership essentially repaid it with Scurtis’ portion of the profits, but still reported Scurtis’s income to the Internal Revenue Service, as it should have, the judge said.

Scurtis claimed that after his ties with the partnership were severed, the venture tried to commit insurance fraud by inflating damages caused by Hurricane Ike. And it also tried to commit mortgage fraud by making it look like the properties had a healthy cash flow: Rodriguez employees allegedly were asked to pay rent as if they lived in the apartments, Scurtis claimed.

Hanzman countered that no civil or criminal actions were filed over the alleged insurance and mortgage fraud. Even if there were such frauds, they “were not directed at Scurtis, and caused him absolutely no injury whatsoever,” the judge wrote.

The ruling is good news for Rodriguez, as the racketeering and theft claims would have exposed him to triple the amount of any damages Scurtis might win in the ongoing case.

“The court’s conclusion in the order speaks for itself,” said Rodriguez’s attorney Benjamin Brodsky.

Scurtis’ attorney was less happy, although she pointed out this is not the end of the battle.

“We strongly disagree with the court’s ruling,” Katherine Eskovitz said in an emailed statement. “We intend to pursue this matter until Mr. Scurtis receives fair compensation for his injuries.”

The jury trial starts on Nov. 15 on the remaining Scurtis and Rodriguez claims.