Silverstein, Council strike deal on Queens megaproject

Silverstein, Council strike deal on Queens megaproject

Trending

5 lessons from Silverstein’s Astoria deal

Innovation QNS’ approval tweaks template for mega-projects

There’s no how-to book for developers negotiating for City Council approval of their projects. Or for the Council member on the other side of the table.

“Ulurp for Dummies” hasn’t been published because its target audience is only a few dozen developers and 51 term-limited City Council members.

In its place, The Real Deal brings you an abridged version, prompted by the big rezoning deal reached Thursday for the Innovation QNS project in Astoria. Our guide’s shelf life is limited by the city’s ever-changing politics, neighborhoods and economy, but should be good until the Democratic primary in June.

Without further ado, here are five lessons from Astoria:

Don’t negotiate in public.

Most developers know this, but City Council members often fail to get the memo.

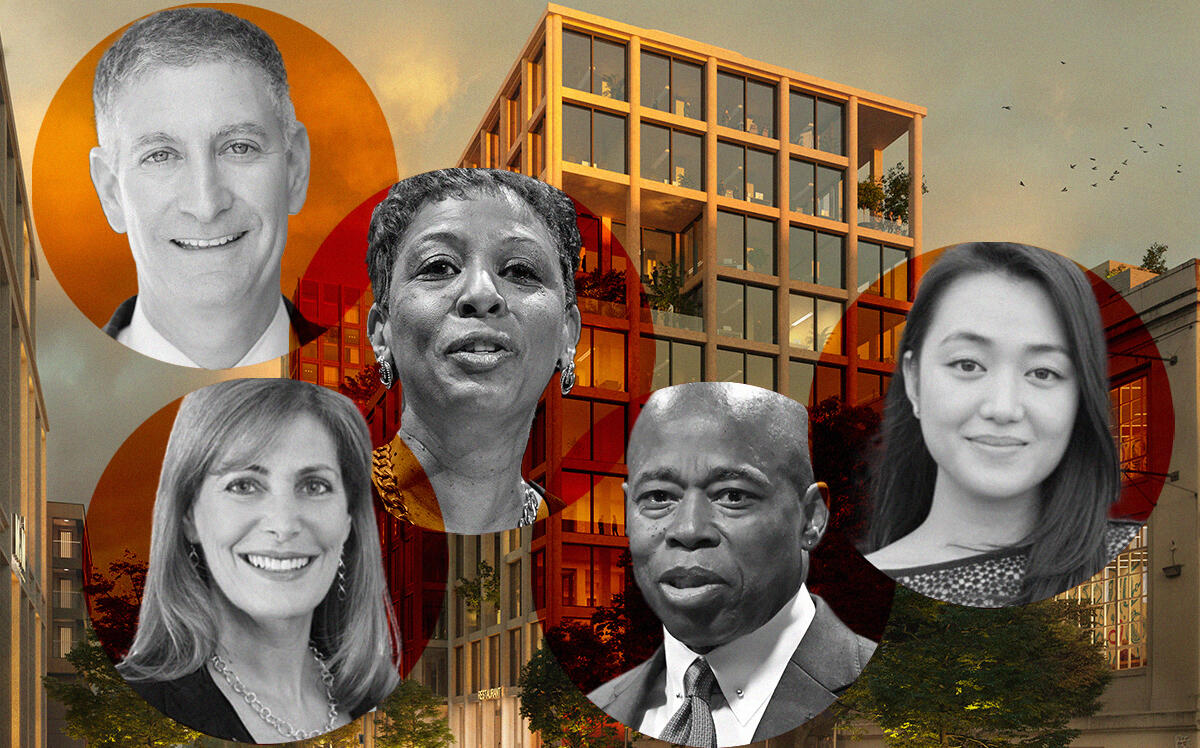

Tiffany Caban got it, and was able to swing a commendable deal for super-low rents in 25 percent of Hallets North’s 1,400 apartments. Julie Won didn’t, and ended up practically apologizing for — rather than celebrating — the 45 percent affordability extracted from Innovation QNS developers Silverstein Properties, BedRock Real Estate Partners and Kaufman Astoria Studios.

As journalists, it is painful to admit, but broadcasting your demands via press release or Twitter makes it look like you got rolled when the eventual compromise happens. And make no mistake, Julie Won got rolled.

“The speaker is driving this train now, not Won,” one source told TRD’s Joe Lovinger, referring to City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams, who had issued a statement in September vowing that her chamber would listen to communities but not “irrational opposition that rejects desperately needed housing.”

Don’t email colleagues for help.

Any message emailed to 50 politicians is almost certain to be leaked, and Julie Won’s entreaty about Innovation QNS was no exception. When Politico reported it, it signaled that Won was not guaranteed the courtesy of member deference — meaning she could not count on her colleagues to back her if she rejected Innovation QNS.

Raising that possibility essentially made it true, weakening Won’s leverage. Although the Council has only ignored member deference once since 2009, that one time was less than a year ago: the New York Blood Center rezoning. And members were ready to do so again with the Throggs Neck rezoning on Bruckner Boulevard last month.

Read more

Silverstein, Council strike deal on Queens megaproject

Silverstein, Council strike deal on Queens megaproject

The rezoning conundrum

The rezoning conundrum

Vice squad: Project foes put squeeze on Brooklyn pol

Vice squad: Project foes put squeeze on Brooklyn pol

Economics has laws, not morals.

Opponents of Innovation QNS seemed to regard its apartment rents to be a moral decision by developers. These are billionaires, the critics said. Why can’t they go all-out on affordability to house New York’s poor, tired, huddled masses?

Those words are etched into the Statue of Liberty but have never appeared on a loan document.

Larry Silverstein appears to be the only billionaire in the development group, and he didn’t become one by building projects that don’t make money. But even if he wanted to, Innovation QNS could not get financing if its projected return on investment did not meet lenders’ benchmarks. No financing means no project.

Thus, making affordability a morality play was nonsensical, except as spin. And spin doesn’t get a deal done.

Race matters.

In lily-white suburbs and some enclaves in the five boroughs, the prospect of building apartments into which poor people of color will move generates opposition. But among most City Council members, it generates support. That’s why the rezonings in Gowanus and Soho were destined to pass — and probably the Astoria rezoning too.

Won, the local Council member, tried to portray Innovation QNS as certain to displace working-class immigrants, but by and large, her colleagues didn’t buy it. They saw the project as supplying more than 1,000 affordable units in a good neighborhood, the kind where Black and Latino families can thrive.

It was a rare chance to build low-income units at scale in someplace other than poverty-stricken areas far from economic opportunity and high-performing schools, which is where affordable housing usually goes. For that reason, Won had to get to yes, and if she didn’t, the Council’s first Black speaker would override her.

The mayor is paying attention.

Since late summer, Mayor Eric Adams has been beating the drum for housing, and his message is resonating. In interviews and public appearances, he talks constantly about how New Yorkers are always calling for affordable housing, then rejecting it when it’s proposed on their blocks. This has made it harder for the “not in my backyard” people to get away with it, and easier for City Council members to defy them.

Adams has even given this position a brand: the City of Yes. It’s become a rallying cry, which the somewhat caustic term YIMBY (“yes in my backyard”) has struggled to become, even as the pro-housing movement has gained momentum.

The mayor has proven adept at using language to his advantage. He is leaving project opponents no quarter. Who could oppose the City of Yes? The only alternative is the City of No.