Anyone who’s tried to do business with a serious golfer on a summer Friday — or Monday, for that matter — may be on a fool’s errand.

With an abundance of storied golf clubs in the metropolitan area, the same is true of real estate’s biggest players.

Built on hundreds of acres of rolling hills in Westchester, New Jersey and the Hamptons, golf in the tri-state area is unquestionably a real estate story — sharing a clubby nature with an industry known for being less than hospitable to outsiders.

Though New York’s older clubs are steeped in history, a slew of new courses built over the past two decades have attracted the industry’s biggest names and the imprimatur of golf starchitects who have pushed clubhouse aesthetics into the modern age.

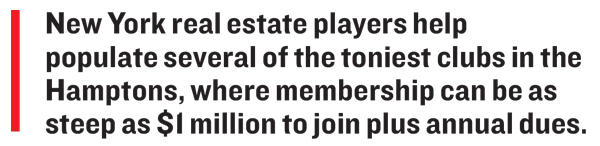

At the Bridge — a 17-year-old club in Bridgehampton whose members include HFZ Capital’s Ziel Feldman and Marty Burger of Silverstein Properties — architect Roger Ferris designed a modern, glassy clubhouse that houses art by painter and photographer Richard Prince and contemporary artist Tom Sachs (both members).

And at East Hampton Golf Club, which opened in 2000, the clubhouse was designed by Pembrooke & Ives, the interior design firm behind the luxury condos at 212 Fifth Avenue and the Astor at 235 West 75th Street, among others. (That club also counts high-profile real estate attorney Jon Mechanic, chair of law firm Fried Frank’s real estate department, and Cushman & Wakefield’s Doug Harmon as members.)

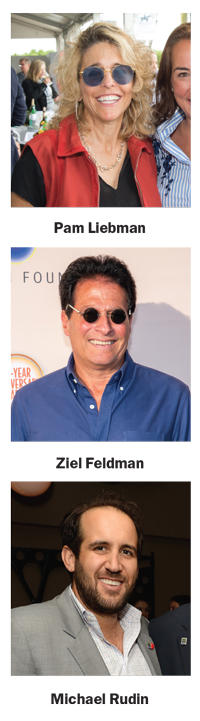

In fact, New York real estate players help populate several of the toniest clubs in the Hamptons, where membership can be as steep as $1 million plus annual dues.

And playing with clients and colleagues is, well, par for the course.

“There’s a lot of quid pro quo going on in golf,” said Robin Schneiderman, head of business development for Halstead and Brown Harris Stevens Development Marketing, who plays at Gardiner’s Bay Country Club on Shelter Island. “I’ll take you to my place if you take me to yours.”

What’s your handicap?

The East End is dotted with exclusive clubs whose membership goes back generations.

Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, Maidstone Club and National Golf Links of America are generally uttered in the same breath — often followed by the words “discerning,” “private” or “snooty.”

Among the top three, Maidstone has been called the “most blueblood.”

The East Hampton club, founded in 1891, is said to have a seven-year waiting list.

Famous members have included George Plimpton, co-founder of the Paris Review. Arthur Zeckendorf is also a member.

Atlantic Golf Club, which opened in 1992 in Bridgehampton, has an equally prestigious (and deep-pocketed) member base.

But early on, it had the reputation of attracting Jewish members who had been turned away from other clubs. Some of those early members included the Blackstone Group’s Stephen Schwarzman and Jonathan Tisch, chair and CEO of Loews Hotels, according to published reports. Harry Macklowe is also said to be a member, sources said. And Corcoran Group CEO Pam Liebman plays there as well.

Liebman said she’s “cemented many a deal over golf,” and plays not just for the chance to spend several hours outside in a beautiful environment, but also to connect with clients and potential clients (often with cocktails on the last hole). It “doesn’t hurt,” she said in a text message, “to often be the only woman playing in small or large groups.”

The strength of a golfer’s game may depend on the day, but there are some real estate players with strong handicaps.

John Leslie, senior managing director at ABS Altman Warwick, the capital markets arm of ABS Real Estate Partners, has a 3.4 handicap — meaning that on average he scores 3.4 above par on 18 holes. Steve Witkoff’s handicap is 4.4, according to the Golf Handicap and Information Network, which is maintained by the U.S. Golf Association. Two Trees Development’s Jed Walentas has a handicap of 4.8.

CBRE’s Paul Amrich went to college on a golf scholarship and almost went on a PGA development tour. “In hindsight, I’m really glad that I didn’t,” he told the Commercial Observer this year. “Those guys lived out of the trunk of their cars, and they’re not playing professional golf.”

Not unlike co-op boards, golf clubs have strict admissions policies requiring sponsorship by a current member and hefty financial outlays. Even then, some decisions are shrouded in secrecy. Membership at the most elite clubs are often passed down from family members.

ABS’ Leslie said they probably take 10 new members a year. “There’s a lot of people vying for those eight to 10 spots,” he said.

Too many clubs

The fact is, there’s a surplus of golf courses thanks to a building boom in the 1980s. But over the past decade, the number of golfers has dropped off.

An estimated 24.2 million Americans played golf in 2018, down from a peak of 30 million in 2001, according to the National Golf Foundation. That steep decline, partly a result of the sport failing to attract millennials, has taken a toll on golf clubs.

“The number of closures has outpaced openings for a 10-year period now,” said Jeff Davis, founder of Dallas-based Fairway Advisors, a golf course brokerage and advisory firm. Nationwide, there are around 16,700 courses — with around 12 courses opening and 198 courses closing in 2018 alone.

Courses that were built purely as amenities for residential projects are particularly vulnerable. Great Rock Golf Course, an 18-hole course in Wading River on Long Island, was designed in the 1990s with 140 homes. By the early aughts, the club ran into financial trouble after trading lawsuits with the town and defaulted on its taxes, according to local news reports. In 2014, it was sold out of bankruptcy. The course is still private, but it’s unclear who the new owner is.

But even if a club isn’t financially underwater, the land itself can be more valuable as a development site.

In 2017, Elmwood Country Club, a member-owned club in Westchester, was sold to New Jersey-based Ridgewood Real Estate Partners for $13 million. The developer is now planning 175 townhouses on the 106-acre property.

Toll Brothers, meanwhile, is building residential projects on two former courses in New Jersey. The firm is developing a 78-house project at the former site of Apple Ridge Country Club in Upper Saddle River, where it closed on the purchase in 2015.

And, it’s building 275 homes on the former High Mountain Golf Club, a semi-private club in Franklin Lakes that closed in 2014. The East End’s most elite clubs have been largely immune to the golf course contraction trend, bolstered by status-driven golfers willing (and able) to cough up the dues.

“If there’s an opening to get into Atlantic, there are enough guys out there with the money to do it,” said Fairway Advisors’ Davis. “Same with Maidstone, National and Shinnecock.”

Young blood

Though many of New York’s old real estate families belong to the East End’s blueblood clubs, real estate execs have flocked to a slew of clubs that have opened since 2000.

Sebonack Golf Club in Southampton — which opened in 2006 and costs $1 million to join — counts Witkoff, the Related Companies’ Stephen Ross and Starwood Capital’s Barry Sternlicht as members.

Silverstein’s Burger is said to have joined the Bridge — which opened in 2002 with sky-high initiation fees but lax rules such as no dress code — this year. In addition to Burger and Feldman, other members of that club include Michael May, who runs Silverstein’s debt fund, and Douglas Elliman’s Howard Lorber.

It’s not uncommon to belong to multiple clubs, each with its own reputation, history and course design. Feldman, for example, is also a member at East Hampton Golf Club.

Michael Rudin started playing as a kid with his dad, Bill, and grandfather Lewis, who belonged to Deepdale Golf Club in Manhasset on Long Island. “It has the family connection,” the younger Rudin said of Deepdale, where he still plays, along with Friar’s Head in Riverhead and Atlantic.

Rudin said his grandfather’s legacy there extends beyond club membership: Lewis Rudin founded First Tee, a youth development organization that offers scholarships to students who get into New York University.

Mixing business and golf is either de rigueur or an absolute faux pas, depending who you ask.

Several years ago, ABS’ Leslie met his now-boss Brian Warwick at Winged Foot in Mamaroneck in Westchester, where they are both members. (President Trump is also a member.)

“I actually had heard of Brian years ago through Peter D’Arcy [head of New York for M&T Bank], who is also a member,” said Leslie. Warwick said he “definitely” uses the club to cultivate relationships and show clients a good time.

“They love to come and play at these places because they’re pretty nice places to belong to,” said Warwick, who is also a member at National Golf Links of America, which opened in 1911 and counts billionaire and ex-Mayor Michael Bloomberg as a member.

Kal Dolgin, co-president of Kalmon Dolgin Affiliates, said for years he and his brother, Neil, played at Engineers Country Club on Long Island, where their father belonged.

Israel Dolgin forged strong relationships with a generation of members, who like him were largely self-made children of immigrants. They discussed family and business on the course, which “became an extension to the proverbial boardroom,” Dolgin said.

In 2017, the Dolgins joined other clubs after Engineers was sold for $20 million to Scott Rechler’s RXR Realty Investments. (RXR has since poured millions of dollars into the facilities, located in Roslyn near two of its residential developments.)

Almost everyone in real estate has a “golf story.”

Robert Ivanhoe, chair of Greenberg Traurig’s real estate practice, said he was in his 20s when his then-boss called late one night saying he needed a fourth for a game the next morning. “I had to scramble like crazy,” recalled Ivanhoe, who had to retrieve his golf clubs at 11 p.m. but proceeded to shoot a 72 — giving him street cred with a previously cantankerous boss. (Incidentally, that boss was George Ross, who ended up working for Trump, whose four golf outings at Mar-a-Lago in 2017 cost taxpayers $13.6 million, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office.)

For his part, Rudin said he’s never played with someone to get a deal done, but conceded that “at some point it’s inevitable whether you’re doing business with someone — or not — to talk about business” while playing.

He and his dad still make a point of taking their longtime bankers out for a day of golf at least once a year. “We usually have it be me and my dad versus the two bankers,” he said. “It takes the hierarchy of client versus lender out of the equation, and we’re just playing as four people on the golf course. It’s the great equalizer, to some extent.”