Bay Area developers prepare for new proposals under SB 9

Bay Area developers prepare for new proposals under SB 9

Trending

Attorney general warns Pasadena on SB 9

Mayor to state’s top legal officer: “Why are we playing semantics with this?”

The California attorney general has issued a very public warning to the City of Pasadena over a recently passed ordinance that seeks to exclude certain areas from the reach of SB 9.

The state law and its sweeping override of zoning restrictions on rental developments in historically single-family neighborhoods has become increasingly controversial at the local level. Various cities have enacted ordinances that effectively restrict the development of units on single-family lots, using methods ranging from difficult design standards to rent control.

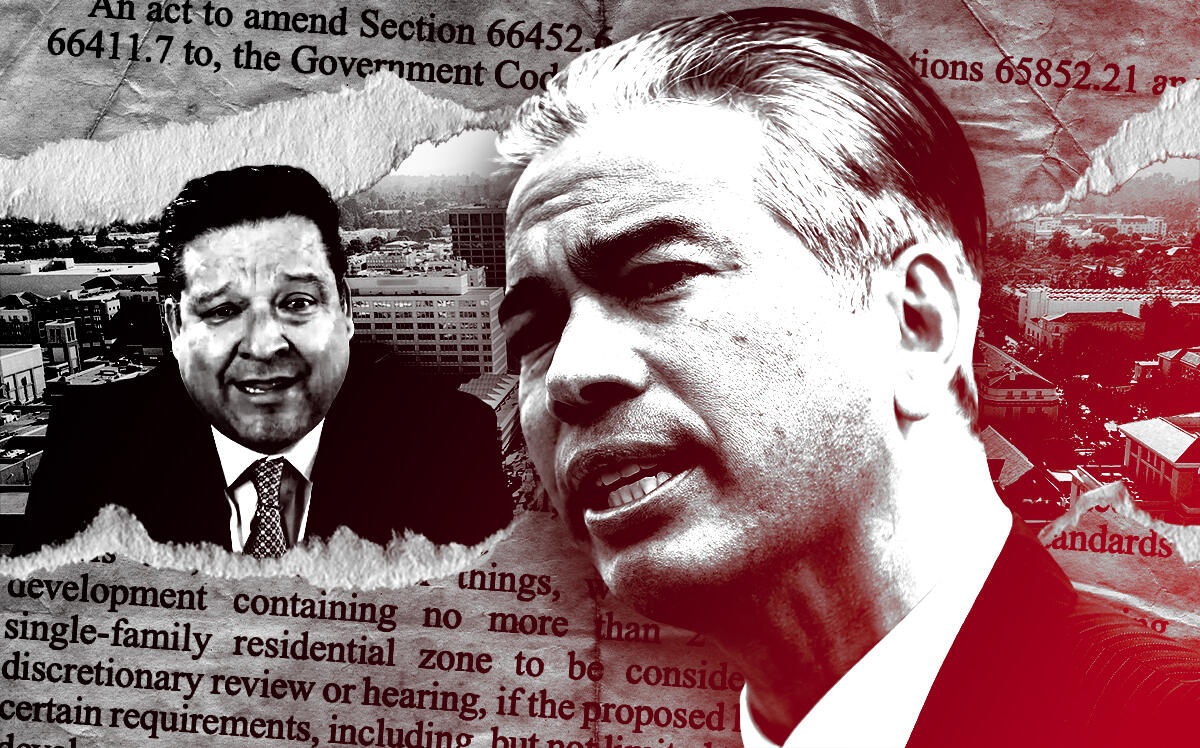

Now Pasadena’s recent passage of an “urgency ordinance” has drawn the highest profile response yet from California Attorney General Rob Bonta, whose office is charged with enforcing state law.

“Pasadena’s urgency ordinance undermines SB 9 and denies residents the opportunity to create sorely needed additional housing,” Bonta said in a statement issued on March 15. “This is disappointing and, more importantly, violates state law.”

In an extended interview with The Real Deal, Pasadena Mayor Victor Gordo rejected the state office’s claim that the city was attempting to circumvent the law. He insisted that Pasadena’s ordinance, which declares certain neighborhoods exempt from SB 9 development, is actually in compliance under the language of the state law.

“What we’re doing in Pasadena is protecting historic assets and neighborhoods and homes that have historic value — it’s part of what makes our city so beautiful,” Gordo said. “And for anyone to assert it was intended as a workaround to SB 9 is absolutely incorrect — when we developed the historic ordinance in the 1980s SB 9 was nowhere in existence.”

Gordo also objected to what he characterized as the unprofessional conduct exhibited by the state office in the matter. He said that Bonta called him an hour before publicly releasing a strongly worded letter, addressed to him, that outlined the state office’s claims against the city — a message that was followed up by a Tweet from the attorney general, who said his office is “putting the City of Pasadena on notice for violating SB 9.”

“I urge cities to take seriously their obligations under state housing laws,” the Tweet continued. “If you don’t, we will hold you accountable.”

“I take exception to that,” Gordo said. “I don’t think Twitter is a good way to govern.”

Bonta did not suggest any next steps that might be taken against Pasadena. Gordo added that he thought Bonta — who weeks ago issued a similarly stern warning to a wealthy Bay Area town that had claimed it was exempt from SB 9 because of the local mountain lion population — was singling out Pasadena because of its stature.

“I think we’re a high profile city,” he said.

In the letter to Gordo, the attorney general claims that Pasadena’s measure, although it’s called an “urgency ordinance,” does not actually meet the legal requirements for urgency ordinances, because it fails to identify harm that would be caused related to public health or safety.

But the dispute also centers around the extent of local exemptions that are permitted under SB 9, which broadly mandates that cities must allow property owners who choose to do so to split an individual lot and turn single family homes into duplexes. Under the language of the state law, cities can allow for exceptions to potential development for “landmarks, historic properties, or historic districts.”

But not “landmark districts,” according to Bonta, whose letter declared that Pasadena’s urgency ordinance “is thus contrary to the plain text of SB 9 and cannot stand.”

Pasadena has designated some two dozen such landmark districts, in addition to 20 historic districts, according to a city webpage. The landmark districts are groups of homes that the city has deemed to have local architectural or historical value. One example — an area known as Glen Summer — was designated because it has dozens of 1930s-era homes that were built in the Spanish Colonial Revival and English Cottage Revival styles, according to a historical society presentation.

The historic districts constitute less than 20 percent of Pasadena’s residential land, according to Gordo.

In order to receive the designation a minimum of 60 percent of the homes within the district must conform to the district’s character, a less-than-blanket requirement cited by Bonta. The attorney general’s office also asserts that, after passing its urgency ordinance, Pasadena intends to designate more of landmark districts expressly to forestall SB 9 development.

“It’s absolutely not true,” Gordo countered.

The mayor also argued that the qualms about “historic districts” — which are exempt from SB 9 — and “landmark districts” — which are not — amounted to a hollow debate.

“We’re saying, No, they’re one and the same,” he said. “Why are we playing semantics with this?”

Last year, an analysis by UC Berkeley predicted that over a span of years the signature state law could have a significant but relatively modest impact, especially because it wouldn’t actually make financial sense for most property owners to develop their lots. Many municipal leaders and their constituents, nevertheless, have strongly opposed the pro-development law on the ostensible grounds of everything from a loss of local authority to concerns about yard space for children.

“These are going to be ongoing battles,” Eric Sussman, a real estate and accounting professor at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, said last month. “There’s nothing new here in terms of politics and power and division, but unfortunately this particular one has significant and long lasting consequences on a large number of people … This is front and center of what matters to people in the state.”

In addition to the Bay Area enclave of Woodside, which quickly retracted its mountain lion argument, in recent months dozens of cities around the state, including Pasadena’s neighbor Alhambra, have passed local measures intended at curbing the law. The ordinances often seek to exploit provisions in SB 9 that allow cities to add “objective” local design standards, by introducing onerous requirements on everything from setbacks to fire hydrants. The attorney general’s office, meanwhile, has maintained it’s monitoring the municipal activity but has so far mostly been mum on how it intends to deal with the violations, setting the stage for a potential standoff that raises plenty of questions about the long term viability of the newly enacted signature housing law.

The immediate future of Pasadena’s ordinance also remains unclear.

Gordo, who opposed SB 9 before it was enacted, said the city plans to study the attorney general’s claims and issue a response. Pasadena could also potentially amend its new ordinance, he said.

“We’ll do that through consultation with the attorney general’s office,” he added. “Certainly not through Twitter.”

Read more

Bay Area developers prepare for new proposals under SB 9

Bay Area developers prepare for new proposals under SB 9

SB9 starting to sound like Prop 13

SB9 starting to sound like Prop 13