Trending

Will Coronavirus Trigger “Force Majeure” Clause in Real Estate Contracts?

Whether or not the commercial property sector collapses will depend on how the industry is able to negotiate this crisis—figuratively and literally

We are all witnessing one of the most dramatic changes to the world’s economy in modern history. The COVID-19 virus has brought life for many to a screeching halt. It has sent our financial markets tumbling and has prompted governments to force the closure of any non-essential establishments. The world seems to be moving so fast that even as I write this I struggle to stay up-to-date. I suspect I will be switching to a news search tab regularly, a habit that has become a borderline neurosis for most of us, to make sure that my references reflect the most recent announcements.

Right now, it seems like there is still so much that we don’t know about this virus. What we do know is that we are all going to feel the effects of it, albeit disproportionately. Already we are seeing the first economic casualties of a viral lockdown. Restaurants and other businesses have been forced to close in major cities around the world. In New York, many workplaces are now required by law to keep seventy-five percent of their workforce at home. California has issued a statewide stay at home order. Stores and hotels and offices and movie theaters and casinos and gyms and even mortuaries around the world are shutting their doors, not knowing when they will be able to open them again. As businesses look ahead to the prospect of not being able to operate for the next few weeks or months, they will face many hard decisions. One of the biggest of which will be whether or not to pay rent.

Under normal circumstances, a business downturn wouldn’t be grounds for missing rent payments. But these are not normal circumstances by any means. Governments have so far showed signs that they are willing to step in to help keep the property industry and the country afloat. New York state has announced that they will suspend mortgage payments for those with financial hardship and trade groups like the Housing Policy Council are recommending banks allow borrowers to stop their payments during the crisis. Now the federal agency overseeing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-run buyer of mortgage debt, ordered a suspension of foreclosures and foreclosure-related evictions for at least two months. The move is meant to keep people in their homes and avoid a housing squeeze like the one that followed the mortgage-fueled financial crisis of 2008. These measures are mostly focused on the residential real estate sector. No one wants to see the kind of downturn we saw in 2008, with massive foreclosures that forced tens of thousands of families out of their homes and stressed our financial industry to the point of failure.

Commercial tenants have also seen some governmental backing as cities like Seattle and San Diego have put a temporary ban on commercial real estate evictions. But this is only a stopgap measure for businesses, it is unknown if the government has the appetite to set in to save every struggling business, especially as the funds are needed to keep people sheltered. Plus, the commercial real estate sector is structured differently than the residential one. Many buildings have no debt while others have incredibly complicated structures that involve layers and layers of financing. Also, commercial loans are packaged into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) at the same level they are for home mortgages. The commercial mortgage-backed securities market is around $190 billion while the residential MBS market is somewhere around $9 trillion. None the less, the CMBS market seems to have halted for the time being.

Most importantly, when it comes to commercial real estate, everything, even the valuation of the buildings, revolves around the ability to collect future lease payments. So the question remains, what happens when businesses don’t pay their rent, even temporarily?

First, a determination will have to be made about whether or not failure to pay rent in the midst of entire states being told to stay at home is a breach of a lease contract. Many leases have what is called a “force majeure” clause. This phrase means “superior force” in French, and frees parties in a contract from their liabilities when an “extraordinary event” or “act of God” prevents them from fulfilling their obligations. This virus could easily be considered either of those, depending upon your belief system. So how will the real estate industry react? Or to put it more bluntly: who will be stuck taking the losses for the unpaid rents?

Read more from propmodo

Mike Jaworski, managing director at CREModels, a consulting services and software creator for commercial real estate told us, “There has been some talk in the CRE world for an agreed-upon moratorium for the whole chain, in other words, a 30-60-day freeze on rents payable for tenants as well as mortgages payable for borrowers. This is unlikely to get momentum but is something floating around in some circles. We do not see this as a likely event.” He cited that many force majeure clauses in leases are too generalized to cover this kind of event so they wouldn’t give most tenants an explicit out. He also mentioned that, “Some business interruption insurance policies specifically address pandemics but many do not so there may not be relief there either.”

What about the insurance industry, the very institution that was built to help in extraordinary times like these? It will surely step in to help shoulder some of this burden. Many businesses have Business Interruption Insurance which can cover losses from all sorts of circumstances. Some even have a Civil Authority clause that could apply to government-imposed closures like those we have seen with these pandemic precautions. This might not be the case either. Michael A. Fried, President of Aftermath Consulting Group, LLC., an insurance claim consulting firm, told us that in his opinion, “The textbook answer of “Civil Authority” based on coverage may ultimately not apply.” But that could change if the government steps in. “Think of 9/11 with the government ultimately enforcing the Terrorism Exclusion business insurance coverage despite the policy exclusion for such,” he said.

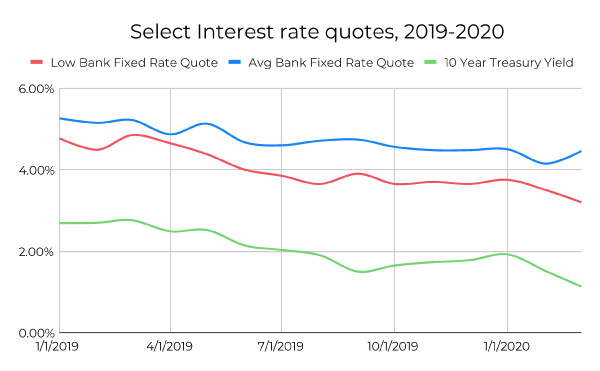

If tenants wind up unable to pay their rent then landlords might not be able to pay their debt payments. This might set up a showdown between lenders and borrowers. “One player in the real estate value chain that has no intention of letting payments slip is the lending community. Mortgages need to be paid or a property will go into default,” said Tim Milazzo, Co-founder and CEO of commercial lending platform StackSource. He has seen two “clear and distinct signals” in the commercial lending market this month. “First, average spreads over 10-year treasury bond yields are widening,” he said. That means that the stated interest rate and the actual rate that money was being lent is getting further apart. The spread is an indicator of the interplay between the supply and demand for commercial real estate debt. A large spread often means that, according to Milazzo, “banks view commercial property lending as a riskier proposition overall.” This is compounded by the uptick in interest in debt that is at an all-time low base rate.

The second thing that Milazzo has seen from the listings on his platform is that the gap between the prices multiple banks are quoting for commercial mortgage deals is also widening. “This means different banks are coping with this situation in different ways. There’s no consensus,” he said. While it looks like some banks are raising their prices in fear, others are looking to put more money into commercial properties in lieu of the other investment options.

Without any clear understanding of who is legally responsible for paying their rent and debt obligations, whether or not the commercial property sector collapses will depend on how the industry is able to negotiate, both figuratively and literally, this crisis. Brian Snow is a twenty-five year veteran in the commercial real estate industry and is now an active tech investor and vice chairman of the building management platform Eden. “We all need to do the right thing and proactively identify who might struggle to pay rent,” he said. This will make any future negotiations much more amicable. Plus, as Snow pointed out, “a one-time write-down is much easier to plan for than mass vacancies in a turbulent market.”

As hard as it is to swallow an unforeseen loss, this negotiation process is exactly what might keep the industry from total collapse. Snow explained, “In residential, real estate properties are highly leveraged and the notes are inflexible because they are packaged into a whole web of securities. When payments are not made there is often no option but to foreclose.” The same is not true for lease payments, which often get renegotiated during extraordinary economic events. Plus, he says that being proactive with lenders is also important. While they are not likely to forgive debt, “Lenders don’t want to take buildings back, they don’t have the resources to manage them,” Snow said.

In the face of this kind of emergency, health and safety is the most important thing. We all now understand our responsibility in limiting the damage from this destructive virus. Shutting down businesses and sheltering in place is the right thing to do. But this will take its toll on our economy, and the property industry that supports it. Relationships like those between landlord and tenant or lender and borrower might seem like zero-sum ones. The reality is much more complicated. If we find a way to spread the burden of this shutdown in a fair, even way between everyone we may be able to patch the cracks in the system before we see a catastrophic collapse like we did in 2008. In order to keep losses to a minimum and return to our previous lives as soon as possible, it is important to look at the economic impact of missed rent payments on the commercial property industry and what everyone can do to mitigate the damage.