Left: The Corner on 72nd Street. Inset, developer David Picket. Right: Liberty Luxe and Liberty Green in Battery Park City. Inset, developer Howard Milstein.

New York City developers are relieved that the market has picked up, but many have been caught off guard by the sudden change in buyers’ preferences.

To adapt, New York developers are speedily altering unit sizes and floor plans in upcoming projects and those already on the market — sometimes even before construction is finished.

Lower-end apartments are getting smaller to accommodate value-seeking buyers, and make it easier for them to get mortgages. At the other end of the spectrum, developers are combining more condo units to create larger apartments — sometimes at the request of specific buyers, other times in a preemptive attempt to target families or others looking for more space.

“Developers are doing everything they can to accommodate any potential buyer, so if it takes combining a unit, you combine a unit,” said Gerard Longo, the developer of new Tribeca condos Pearline Soap Factory and the Fairchild.

But creating these larger units can be hazardous for developers, so many have started hedging their bets with flexible layouts that can be refashioned into more than one configuration — depending on who comes knocking.

“It’s risky to do anything other than have a variable menu,” said Longo, president of Brooklyn-based Madison Estates and Properties. “Whenever I do a plan now, no matter what the job is, I look at the job and see those [layout] possibilities.”

Recent market changes have vastly altered the makeup of buyers and renters in New York. First, the financial crisis abruptly reduced the number of young, cash-rich Wall Streeters, who were driving much of the market for high-end studios and one-bedrooms.

In response to this trend, some developers are converting studios into one-bedrooms. Others are simply making their one-bedrooms and studios smaller.

“There’s a tremendous demand for units that are under $800,000 for a one-bedroom,” noted the Marketing Directors’ Andrew Gerringer. “People would rather have 1,250 square feet than 1,350 square feet. It’s more affordable and easier to finance.”

At the Solarium in Long Island City, for example, 565-square-foot units that were originally built as studios are now being marketed as one-bedrooms, said developer Joseph Palumbo, who decided to make the change based on feedback from potential buyers after the 35-unit project went on sale in January. That meant adding walls to already built units. But it paid off: About half of the 11 studios in the building have sold as one-bedrooms, he said.

“The one-bedroom is much more appealing for the first-time buyers,” Palumbo said.

A large part of the allure, he said, is that the units — priced in the upper $300,000s to low $400,000s — are “very reasonable” compared to other one-bedrooms. The lower maintenance is also a draw, he said.

At the upper end of the sales and rental markets, meanwhile, many units are getting larger.

Nancy Packes, head of Nancy Packes Inc., said there is a “huge demand” for larger rentals, especially in luxury buildings, in part because more families are staying in the city.

For example, she noted that the new rental by David Picket’s Gotham Organization, the Corner on 72nd and Broadway, has a number of three-bedrooms priced at around $16,000 a month. Packes, who consulted on the project, said if it had come on the market five years ago, the largest units likely would have been two-bedrooms.

But families aren’t the only reason the market for larger rentals is picking up.

Gannon Forrester, managing director at the brokerage New York Living Solutions, said in the past few months he’s noticed an influx of wealthy hedge-fund managers, doctors and lawyers who could easily purchase a $3 million to $5 million apartment, but are opting to rent instead.

With the sales market no longer appreciating rapidly, “I’ve definitely noticed a shift in what they’re looking for,” he said, noting that some of these tenants are willing to pay upwards of $20,000 a month.

“Rather than tying up two-to-three million on a down payment, they can do their own investments [outside of real estate] and get a better return,” he said.

Replacing these buyers in the sales market are value seekers.

During the boom, for instance, the best option for cost-conscious families seeking larger homes was often to buy two resale apartments and combine them. But that’s often no longer the cheaper option because of the drop in prices. Plus, buyers hold more of the power now and can demand (at least in new condos) that developers do the renovation work.

The president of the Marketing Directors, Jacqueline Urgo, said buyers “want to walk in and put their furniture in.”

“Most do not want to live through the stress and work of combining it themselves,” she said.

The Albanese Organization, developer of the Visionaire in Battery Park City, combined units for eight buyers, Urgo said. And at Milstein Properties’ nearby condos Liberty Luxe and Liberty Green, where sales started in early summer, the Marketing Directors is getting similar requests.

These preferences have in some cases caught developers off guard.

“The percentage of [demand for] large-scale apartments is surprising them, [but] they’re responding,” said Barry LePatner, a founding partner at construction and real estate law firm LePatner & Associates.

At the Brompton on East 85th Street, developed by Stephen Ross’ Related Companies, there was more interest by families in larger apartments than expected, said Susan de Franca, the president of Related Sales.

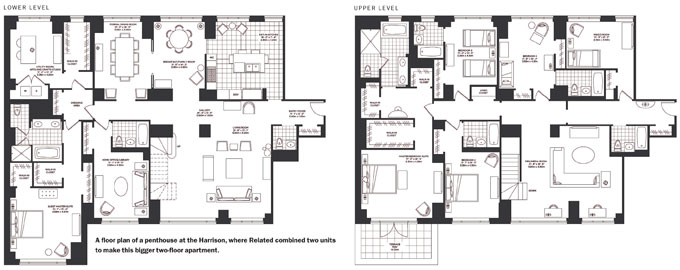

Some of these families specifically requested that their units be combined, but in other cases, Related combined units after construction had started “just based on our observation of market demand,” she said. The number of apartments in the building ultimately fell from 193 to 163. A similar pattern occurred at the Harrison, on West 76th Street, which originally had 132 units but now has 125.

And there are other kinds of reconfigurations taking place.

At the Sheffield — the 57th Street condo conversion which was known as Sheffield57 before Fortress Investment Group bought it in a foreclosure auction last year — two of the five bedrooms in one 3,000-square-foot apartment are being combined to create a larger master bedroom suite, according to the Marketing Directors, which is handling sales at the complex.

Previous owner Kent Swig had combined two apartments to create the five-bedroom layout before the Marketing Directors took over. But when potential buyers saw the newly completed apartment, they suggested that a larger master bedroom would be more appealing, so the new owners decided to make the change, Urgo said.

This kind of move can be risky, since there’s no guarantee a buyer will come along to justify the expense. “People have shown interest, but have not yet come to the table with the $7.5 million,” Urgo noted.

Still, developers are often willing to take a chance in the current market.

“They’ll do anything to sell these apartments,” LePatner said.

This kind of flexibility has become crucial. While building the Pearline, Longo discovered that buyers wanted larger units than he had expected. In response, the two units per floor were combined to create 3,000-square-foot, floor-through units.

He also decided to make units bigger at the Fairchild. But because smaller units are often more profitable per square foot and there are more buyers who can afford them, he hedged his bets, creating 1,500- and 2,000-square-foot apartments, designed so that they could be easily combined. It appears to have worked; 17 out of the original 21 units have sold, and two of the purchasers combined two 2,000-square-foot units.

“We didn’t want to take the risk of being caught with all these large units,” he said. “We knew there would be a smaller pool of purchasers that we would be fishing in.”

For the foreseeable future at least, “I would stay in that safe zone of offering the combination possibility,” he said.