UPDATED, 3:41 p.m., Oct. 23: A new technology, designed to tame forces that could separate an astronaut’s eyeball from her retina, may also keep the one percent from throwing up.

NASA developed the device, dubbed a fluid harmonic disruptor, to protect occupants of its Ares 1 rocket from violent vibrations during takeoff. And now, Thornton Tomasetti, a structural engineering firm, is looking to it as a way to prevent nausea atop some of New York’s loftiest buildings.

Building movement is pretty routine. Most skyscrapers sway in the wind to varying degrees, with the taller and thinner buildings often feeling more of an impact. These movements can cause those living or working high up in these buildings to feel awfully queasy — not something a hedge fund titan or the buyer of a castle in the sky wants to deal with. Developers counter these movements in a number of ways, but Forest City Ratner’s B2 BKLYN, a new modular tower planned at Pacific Park, is the first to get the fluid-harmonic treatment, according to Rob Berry, NASA’s project manager for the technology.

Here’s how it works. Six water-filled pipes on the roof of the 32-story building — making up about 0.5 percent of the building’s total mass — will stymie the tower’s vibrations. The NASA-designed disruptor will control the water’s movement and change how the liquid and building would usually react when wind or other vibrations occur. The system, Berry said, changes the “fundamental attributes” of the building.

For the physics-averse, think of the device as a balloon in the water. If the balloon contracts, the water moves toward it. If it expands, the water is pushed away.

“It’s about changing the way those masses play,” Berry said. “We’re tying a brick on the dog’s tail. The dog can’t move its tail.”

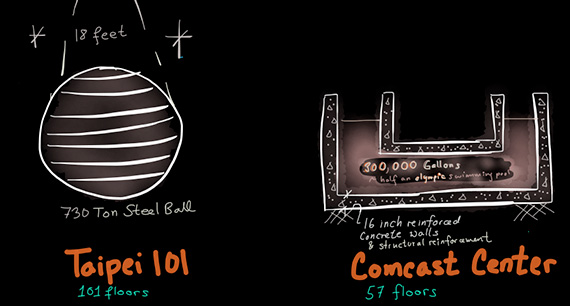

Most skyscrapers use a different technology, called a tuned mass damper, which uses a steel or concrete weight to resist movement and giant tanks of water to weigh down the building, said Steve DeSimone, president of DeSimone Consulting Engineers.

Taipei 101 in Taiwan, one of the world’s tallest skyscrapers, has a giant tuned mass damper in the form of a sphere suspended between the 87th and 92nd floors. The device sways in the opposite direction of the building’s to neutralize the wind’s force. With towers getting taller and thinner in New York, dampers are increasingly coming into play in buildings here, including 111 West 57th Street, 432 Park Avenue and 220 Central Park South.

An explanation of the Tuned Mass Damper technology (Credit: Thornton Tomasetti)

But buildings shorter than 800 feet typically don’t require them, DeSimone said, adding that he “wouldn’t put a damper on a 32-story building.”

Dampers also typically require some movement to kick them into action — a system often compared to a pendulum— which Berry sees as a pitfall, especially when something like an earthquake requires an immediate reaction.

Thornton Tomasetti, which has the exclusive right to apply the fluid harmonic disruptor to tall buildings in the U.S. and is bringing it to B2, is billing the technology as a cheaper and lighter alternative to traditional dampers. Elisabeth Malsch, vice president of Thornton, said tuned mass dampers are often considered “luxury items,” included only in the tallest of tall buildings. However, building materials have become lighter and more efficient, making dampers increasingly important for stability.

Rendering of a fluid harmonic disruptor

Those who pay for sweeping, panoramic views at the top of buildings are also those who are the most vulnerable. “For wind-induced vibrations, it’s the top of the building. It’s always the top of the building,” Malsch said. “The beautiful penthouses would have the maximum accelerations.”

Thornton hopes to eventually apply NASA’s technology to taller skyscrapers, but for now, B2, which is evenly split between affordable and market-rate units, will be the first to try it out. The polyvinyl chloride pipes, each three feet in diameter, will be installed once the building is completed, which is slated to be early next year, Malsch said.

Robert Sanna, director of construction and design at Forest City, said B2’s lightweight modular material necessitated the use of a disruptor.

“Some people are more susceptible to feeling the sway than others,” he said. “This being a residential building, we are concerned about the comfort level of the residents.”