UPDATED: April 27, 2:16 p.m.: Housing in the U.S. has become a two-speed market – and New York is stuck in the slow lane.

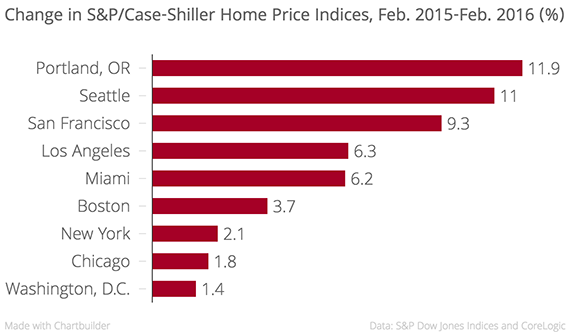

The S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index for New York City grew a mere 2.2 percent year-over-year in February. But it’s not just the Big Apple that saw its prices plateau: Boston’s index grew by a modest 3.7 percent, Chicago’s by 1.8 percent and Washington D.C.’s by a mere 1.4 percent.

Meanwhile, price growth in Seattle and Portland reached double digits, with San Francisco trailing closely at 9.3 percent.

The Case-Shiller Index doesn’t include condos and co-ops, which makes it an imperfect indicator of the New York residential market. But condos and co-ops are caught in a similar slowdown. A recent Streeteasy report found that Manhattan’s median apartment resale price grew 4.4 percent year-over-year in February – the slowest growth since October 2012. Streeteasy forecasts that growth will slow down to 3.2 percent over the coming year.

New York’s residential slowdown isn’t news, but so far most observers have treated it as an isolated, local phenomenon. The Case-Shiller report suggests it is really part of a national trend: a divide between slow growth in major markets in the northeast and a boom in the south and on the west coast. What explains it?

“There is one difference and that is job growth,” said Ralph McLaughlin, chief economist at listing site Trulia. Last year, he said, the number of jobs in Seattle and Portland grew by 3.2 percent each – compared to 1.4 percent in New York City, 1.8 percent in Boston and 1.7 percent in Chicago. The big West Coast cities have been particularly successful at attracting well-paying tech jobs. Growth in well-paying jobs tends to push up prices the higher end of the real estate market, which carry a disproportionate weight in the Case-Shiller Index.

Despite its much-hyped tech boom and the coming Cornell Tech campus, New York added a mere net 3,000 high-wage technology jobs for 18-to-29-year-olds between 2000 and 2014, according to a new report by comptroller Scott Stringer, while losing a net 10,000 jobs in finance.

A second explanation for the discrepancy is cyclical. New York recovered more quickly from the recent housing slump than other cities. The latter are now belatedly catching up – as they tend to do in most cycles. McLaughlin calls this dynamic “economic convergence.” It helps explain why prices in cities like Tampa, Dallas and Las Vegas also grew far more quickly than in New York last year. In this sense, slow price growth in the Big Apple is actually a sign of the market’s strength.

Correction: an earlier version of this post omitted the fact that condos are not included in the Case-Shiller index.