Hasidic investors and developers have transformed Brooklyn, but they remain in the shadows (Illustration by Lexi Pilgrim for The Real Deal)

TRD Special Report: On the day before Thanksgiving, Yoel Goldman phoned one of his go-to lenders with an urgent request.

The Brooklyn developer, who heads All Year Management [TRDataCustom], wanted to score a construction loan for his Albee Square project by Monday, which gave him just one business day to make it happen.

The lender, Gary Katz of Downtown Capital Partners, reminded him of Thanksgiving. But Goldman, who is from the Satmar sect of the Hasidic branch of ultra-Orthodox Judaism, countered: “So you can’t work Thanksgiving tomorrow, but you still have all of today, Friday and Sunday.’”

Katz tried an analogy. Wednesday, he told Goldman, is Erev Yontiff – “evening before the holy day” in Yiddish – and Friday is Chol HaMoed – a weekday between two holy days. For most Hasidic Jews, Chol HaMoed is an occasion for family and Talmud study, not dealmaking.

Goldman got that, and held off. Property records show he ultimately received a $25 million mortgage from Downtown Capital and RWN Real Estate Partners – on Christmas Eve.

The real estate investors who hail from Brooklyn’s insular Hasidic communities are some of the industry’s most active and powerful players. Over the past decade, they’ve spent more than $2.5 billion on acquisitions in five prime Brooklyn neighborhoods, according to an analysis of property records by The Real Deal. But unlike their Grill Room-dining, art-collecting Manhattan counterparts, they prefer to stay in the shadows, their connections to properties masked through a network of frontmen and a labyrinth of LLCs. Most have no websites, and some have never been photographed.

This immense cultural divide hasn’t stopped them from transforming key neighborhoods into yuppie central, where rents and sales prices have skyrocketed. From the second quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2016, the average apartment sales price in Williamsburg doubled – from $668,956 to $1.3 million, according to real estate appraisal firm Miller Samuel. The average sales price in Bedford-Stuyvesant jumped 67.8 percent, to $877,225, and average monthly rents in Bushwick jumped 70.6 percent, to $2,643. Borough-wide over the same period, the average sales price climbed by 38.8 percent, to $816,827, and average monthly rents rose 26.2 percent, to $3,137, the data show.

Read more

“The Hasidic community helped create the frenzy [in Brooklyn] we have today,” said Pinnacle Realty’s David Junik. “They let the market explode after that.”

A clandestine empire

Any Brooklynite could tell you the Hasidim are prominent landlords in the borough. But the extent of their dominion long remained unclear.

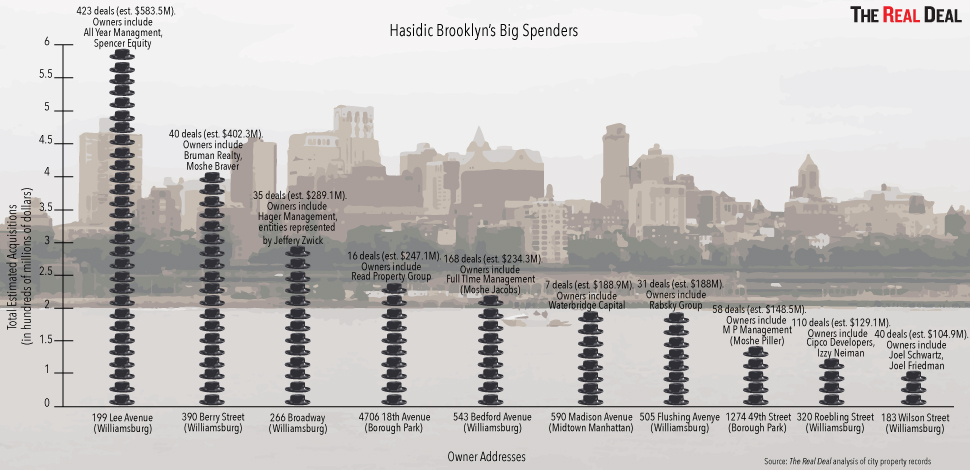

These 10 addresses in Hasidic Williamsburg are linked to over $2.5 billion in real estate purchases (source: The Real Deal analysis of city property records)

TRD reviewed every building purchase in five of the borough’s fastest-growing neighborhoods – Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Bushwick, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Borough Park – between January 2006 and mid-June 2016. Over this period, 10 addresses – affiliated with one or more firms – were each responsible for at least $100 million in purchases. The analysis included only addresses where the total expenditure involved five or more separate purchases, indicating repeat bets on neighborhoods. Firms like Forest City Ratner, Two Trees Management and Spitzer Enterprises, for example, also spent big on these neighborhoods, but made fewer deals.

The 10 addresses (see chart above) were predominantly clustered in South Williamsburg and Borough Park. In Williamsburg, they include 390 Berry Street, 320 Roebling Street, 266 Broadway, 183 Wilson Street, 543 Bedford Avenue, 199 Lee Avenue and 505 Flushing Avenue. Mapping them out north to south takes you on a walking tour through the heart of the neighborhood’s Hasidic enclave.

The addresses point to a who’s who of Brooklyn real estate: Simon Dushinsky and Isaac Rabinowitz’s Rabsky Group; Joseph Brunner and Abe Mandel’s Bruman Realty; Yoel Goldman’s All Year Management; Joel Gluck’s Spencer Equity; Joel Schwartz; the Hager family; and Joel Schreiber’s Waterbridge Capital.

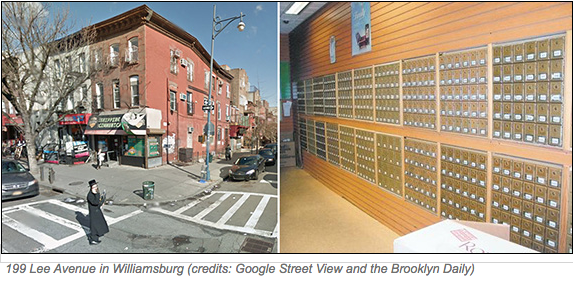

One address, 199 Lee Avenue, is affiliated with an incredible 1,400 LLCs. Over the 10-year period, the mailbox hub on Hasidic Wiliamsburg’s main commercial corridor is linked to 423 purchases totaling $583.5 million, the data show.

Some of the biggest deals were Goldman’s April 2016 purchase of part of the Rheingold Brewery site in Bushwick for $72.2 million, and Goldman and Toby Moskovits’ 2012 purchase of the Williamsburg Generator site at 25 Kent Avenue for $31.8 million. (Goldman is no longer an investor in the 480,000-square-foot Generator office project.)

Dushinsky, Goldman, Brunner and Mandel are considered the heavyweights. Goldman, who is in his mid-30s, owns a portfolio of more than 140 rental buildings. The bulk of his holdings were included in his bond offering on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, and were valued at $850 million, according to a recent filing. He’s also looking to build up to 900 rental apartments at a 1 million-square-foot complex at the former Rheingold Brewery site. Brunner and Mandel, also in their 30s, own more than 100 buildings. Dushinsky, who is in his 40s, has more than 600,000 square feet under development, including a 500-unit project at the Rheingold site. He’s also pushing for a rezoning at the former Pfizer site at the edge of Bed-Stuy that would allow him to develop a 777-unit rental complex.

A rendering of All Year Management’s Rheingold Brewery project (credit: ODA New York)

Most of these investors, believers in the concept of “ayin ha-ra” or evil eye, either didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story or declined to comment. Dozens of market sources who spoke to TRD for this story did so under condition of anonymity, for fear of antagonizing them.

“They believe their success happens because they’re under the radar,” a former employee at a top financial brokerage said. “Blessings come from God for staying private.”

“They believe their success happens because they’re under the radar,” a former employee at a top financial brokerage said. “Blessings come from God for staying private.”

The pious ones

During and after World War II, thousands of Hasidim migrated from places such as Hungary, Romania, Poland and South Ukraine to Williamsburg and Borough Park. Joel Teitelbaum, the founder of the Satmar Hasidic movement, urged the young men to balance their prayers with jobs that would provide for the community. Some went into the diamond trade, kosher foods, garments and light manufacturing. Real estate was particularly appealing because for a long time, Jews in Europe were barred from owning land.

“There was a deeply psychological aspect to owning real estate that drove the first wave,” a source said. “There wasn’t a notion that they could get rich off this.”

Today, their approach to the business is completely different. Hasidic investors — including those from the Vizhnitz, Satmar, Klausenberg and Ger dynasties — are among the fastest-moving dealmakers in the industry, and have jumped headfirst into property speculation and large-scale development.

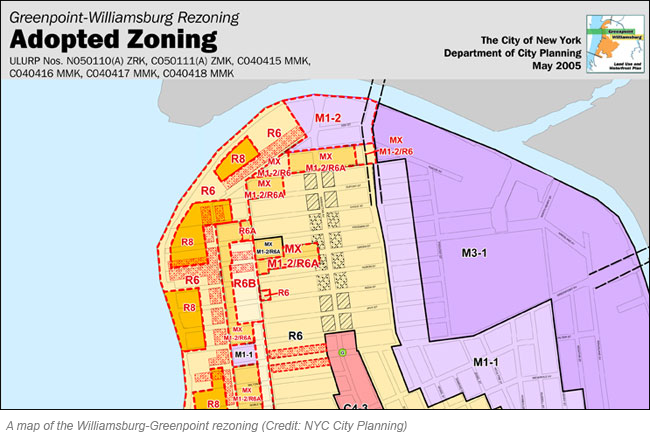

For decades, the Satmars had been lobbying for the Williamsburg-Greenpoint rezoning, which came to pass in 2005 and transformed a roughly 175-block area along the East River from industrial to residential and mixed-use. The rezoning led to a luxury condominium and rental boom in the borough, but when the market turned in 2008, development and lending slowed. A select few Hasidic firms then bought nonperforming mortgages.

For decades, the Satmars had been lobbying for the Williamsburg-Greenpoint rezoning, which came to pass in 2005 and transformed a roughly 175-block area along the East River from industrial to residential and mixed-use. The rezoning led to a luxury condominium and rental boom in the borough, but when the market turned in 2008, development and lending slowed. A select few Hasidic firms then bought nonperforming mortgages.

“A lot of capital withdrew from real estate,” said Gabriel Boyar of Columbia River Capital Advisors, a real estate investment and advisory firm. “Those who remained doubled down and acquired assets at a cheap price.”

By the early 2010s, as the industry recovered, the firms brought those buildings or parcels to market, reaping large gains.

These days, the Hasidim are some of the keenest practitioners of the buy-and-flip, often employing the 1031 deferred-tax exchange to plough profits from one deal into the next. They also use their construction savvy to get projects moving before selling them at a premium.

Rabsky, for example, bought a former silverware factory at 51 Jay Street in Dumbo for $25 million in 2012. Within a year, the firm secured approval for a one-story addition as part of a proposed residential conversion, and then sold the building to Silverstone Property Group for $45.5 million. Silverstone’s Martin Nussbaum and David Schwartz, who later formed Slate Property Group, partnered with Adam America Real Estate to develop it into 73 condo units and a townhouse. The late Satmar president Isaac Rosenberg and his brother Abraham, after securing a zoning variance at 462-484 Kent Avenue, put the site on the market for $210 million, drawing interest from the likes of HFZ Capital Group and Michael Fascitelli.

Blessings come from God for staying private.

The business “became more of a trade than a long-term investment,” said a prominent lawyer for Hasidim-led firms. “They used to look at yield over 30 years. There’s more of a shorter vision now – just two to three years.”

Despite this more frenetic pace, many things remain as they were. Developers often live and work on the ground floor of buildings they own. They’re uncomfortable dining out, unlike the Gary Barnetts of the world who frequent kosher hotspots such as the Prime Grill. Their schmoozing happens at school functions, weddings and synagogue.

Two of the largest Satmar synagogues, located on Rodney Street and Hooper Street respectively, are both called Congregation Yetev Lev D’Satmar. Inside them, investors chit-chat at the ritual bath known as a mikvah. “You see people,” one source said, “and you just bullshit.”

Given that the poverty rate in the Hasidic community — 43 percent, according to a 2011 UJA-Federation of New York study — is the highest among Orthodox Jews, the developers’ patronage of yeshivas and synagogues gives them a lofty status.

“Real estate is not a big employer,” said Philip Fishman, author of “A Sukkah Is Burning: Remembering Williamsburg’s Hasidic Transformation.” “It’s only a few percent of the total community, but some [developers] may be worth tens of millions of dollars and are relied upon to support many of the poor people.”

The ultra-Orthodox enclave of Williamsburg — a top beneficiary of Section 8 housing vouchers — is almost exclusively Hasidic, while Borough Park is home to both Hasidic and Haredi Jews. Due to extremely high birth rates, the Hasidic population in Brooklyn has been forced to spread south of Williamsburg into northern Bed-Stuy and expand its footprint in the heavily Orthodox village of Kiryas Joel upstate, Fishman said.

Along with secular housing, developers like Rabsky continue to build religious housing – “by Jews, for Jews,” as a source put it. The projects typically hold cookie-cutter units that are sold at discounts. There is also a loose rule to preserve housing for fellow Hasidim: If one buys a building owned by a non-Jew, he may market it to hipsters. If one buys a building from a paisan, however, he should keep it as is. Luxury buildings in Williamsburg like the Gretsch – a condo conversion at 60 Broadway by Orthodox Jewish developers Martin and Edward Wydra, where a penthouse sold in 2013 for $4.3 million – faced strong opposition from the Hasidic community.

Though there are occasional displays of wealth among the Hasidim — rich men, or “gvirim,” may sport a felt derby hat from Bencraft Hatters, which offers more than 100 styles — they are far removed from the flashes of excess seen among others in the industry.

“If you don’t have a 72-foot Azimut yacht, two Ferraris and three houses, what the hell do you do with your money?” a source said.

Mishpacha

Mishpacha

The Hasidim have become masters of the deal syndication model pioneered by late titan Harry Helmsley: To make an acquisition, they bring in anywhere from dozens to thousands of small-time equity investors, both local and international. Though their operations have grown more sophisticated, company heads tend to steer clear of dense Excel spreadsheets to run the numbers on a prospective deal.

“These guys are still very old school,” a lender source said. “They’ve memorized half the Talmud – they prefer to do complex calculations in their head.”

Their approach to financing projects also stands out. While firms such as Two Trees Management and Tishman Speyer shoot for the big institutional loan up-front, many Hasidim wait until just before breaking ground to line up funds. They prefer to finance in smaller loan increments over multiple stages, which allows them to tweak their design plans or bring in new partners, and then subsequently restructure the financing, sources said. Josh Zegen, co-founder of Madison Realty Capital, said this approach is “more of a middle-market entrepreneur thing” in general.

“As values increased, some sponsors have refinanced their properties during the course of development, using leverage to return equity to their investors,” Boyar said. Once the property is fully leased and operating, they can secure long-term debt. By contrast, he added, “institutional developers have been able to take advantage of the capital markets and finance their developments early on at lower interest rates.”

If you don’t have a 72-foot Azimut yacht, two Ferraris and three houses, what the hell do you do with your money?

Most Hasidic investors rely on hard money lenders, a cadre that includes G4 Capital Partners, Emerald Creek Capital, Downtown Capital Partners and Trevian Capital. They also tap development and investment firms like Madison Realty Capital and Ari Shalam’s RWN Real Estate Partners, the family office of Apollo Global Management co-founder Marc Rowan.

But some of the bigger players have been able to lock in major banks and other institutional lenders.

In the past year, Rabsky secured $95 million from TD Bank to refinance its debt at Leonard Pointe and an $80 million acquisition loan from Bank Leumi for a development site it bought from Forest City Ratner. For the Rheingold Brewery redevelopment, Madison Realty Capital and Bank Leumi provided acquisition financing — $70 million to All Year and $50 million to Rabsky, respectively.

Other banks that work with the bigger Hasidic firms include Dime Savings Bank, Santander Bank, Centennial Bank, Bank United and Modern Bank, sources said.

Some Hasidim have taken their quest for funds to the the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. Goldman, for example, raised $166 million to date, from a total of two bond issuances. Pooling properties together makes them easier to refinance, a source said. But others in the community, reluctant for the spotlight that comes from being in the public markets, avoid this path.

Amid the deal frenzy, the Hasidim are also dabbling in trading debt.

“These guys are very liquid,” said a prominent financing broker. “You’ll see them very strategically buying notes on properties, but only within their own strike zone. They are very, very good in the markets that they know.”

The outside world

The Hasidim are encouraged to remain insular — except when it comes to business.

Some developers from the community have become especially skilled at making a high-end product for young and upwardly mobile professionals, Jewish or otherwise.

They’ve memorized half the Talmud – they prefer to do complex calculations in their head.

“They’re informed about new trends to the extent that it might be shocking,” said Eran Chen, founder of ODA New York, which is designing the Rheingold Brewery sites for Goldman and Rabsky. “If you sell something and do it well, it’s still not something that you would necessarily buy [for yourself].”

The Rabsky principals, for example, proposed a series of treehouses in landscaped Zen gardens located throughout the under-construction building at 10 Montieth Street. That property will boast a 25,000-square-foot zigzagging landscaped roof for biking, running and gardening.

A rendering of 10 Montieth Street (credit: ODA New York)

“We have conversations about amenity spaces I’ve never had before – typologies that don’t exist,” Chen said. “People have a preconceived view: that they don’t experience the city as we do. But they walk around the projects we do, they read, and they have the ability to quickly gain knowledge.”

The Hasidim are more than willing to do deals with outsiders, brokers said, but it’s not always easy to get their ear.

“If you call an owner in Brooklyn and speak Yiddish, you’re going to get a lot further,” said Gabriel Saffioti, who along with colleague Nicole Rabinowitsch left Eastern Consolidated earlier this year to launch Williamsburg-based brokerage Constellation Real Estate Advisors. Rabinowitsch said she hands out business cards at kosher Williamsburg eatery Gottlieb’s to draw potential clients.

Despite their best efforts, Hasidic investors have recently drawn increased attention — and controversy.

Despite their best efforts, Hasidic investors have recently drawn increased attention — and controversy.

Late last year, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio released a list of landlords with properties that benefit from 421a tax abatements but allegedly don’t offer rent-regulated leases to tenants. Rabsky, which was also accused of abusing preferential rent rules at a Williamsburg rental building in a ProPublica investigation, was one of the landlords. The firm denies the claims.

In March, Allure Group, a for-profit nursing-home operator led by Solomon Rubin of the Borough Park-based Bobov Hasidic sect, made headlines for its role in the controversial $116 million sale of Rivington House to developers Slate Property Group, Adam America and China Vanke. The deal is in the center of multiple investigations, including one by U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara. In June, Schneiderman prevented Allure from closing on two other nursing home purchases, citing the Rivington House deal.

We have conversations about amenity spaces I’ve never had before – typologies that don’t exist. — ODA New York’s Eran Chen

Perhaps the most notorious within industry circles is Chaim Miller, who got his start working for developer Abraham Leser. A recent investigation by TRD found that Miller, whose assets include the Beekman Tower in Midtown East, has been sued at least 18 times since 2014 by at least 29 individuals and entities.

In recent months, the real estate market slowdown has made Hasidic firms, like others, far more selective about deals. But looking at their overall impact over the decade, it’s clear they’ve been the dominant force in shaping Brooklyn real estate.

“For the sake of their business and their community, they need to create an experience they never had,” Chen said. “Through this, there is the opportunity for innovation.”

Yoryi DeLaRosa and Hiten Samtani contributed reporting.