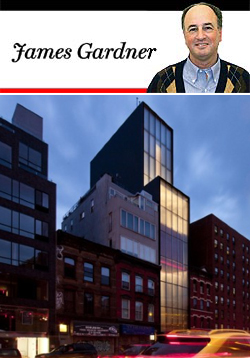

Sperone Westwater gallery (center, lit up) at 257 Bowery

It is always a pleasure to welcome a new building by Norman Foster — that’s Lord Foster to you, by the way. In addition to his peerage, Foster has won architecture’s highest honor, the Pritzker Prize, and has even deserved it — by no means a foregone conclusion among Pritzker laureates. His reworking of the British Museum is as fine an architectural performance as we have seen in the past quarter century, and even his somewhat gimmicky Gherkin building, also in London, is dazzling from a distance.

In New York, he has labored with slightly less incandescence, though that may have more to do with the city’s oppressive architecture climate than with his own abilities. At Hearst’s Argonaut Building at 224 West 57th Street and Eighth Avenue, Foster receives a solid B+, and his design for Tower 2 at Ground Zero shows some promise.

But his latest project in New York, the 20,000-square-foot Sperone Westwater gallery at 257 Bowery, falls far short of what he is capable of doing at his best. As for the real estate angle, the single plot site, purchased three years ago for $8.5 million, was clearly chosen because of its proximity to Sanaa’s New Museum, just to the south. A number of small-fry galleries have started to foregather in these parts for the same reason, that potentially lucrative proximity to the mother ship. But none can match the monetary heft of Sperone Westwater, which takes its place as the first serious gallery to question the 10-year-old primacy of Chelsea.

The gallery’s new eight-story building rises five floors to the general level of the other structures in its vicinity, before continuing on in a three-story setback. From the side — notwithstanding the setback — the building looks like a boxy black desk-top tower from the late 1990s. Though there are windows in the back, there are none on the extensive sides of the building. And the frosted glass curtain-wall of the street façade, cascading down in five bays is there for no other reason than to afford pedestrians a rather pointless intimation of the gallery’s massive elevator as it rises and descends. The entrance is decked out in severe black steel — an equally pointless gesture.

Despite such heavy breathing and operatics, this building displays, in its detailing as well as its overall conception, the pat pizzazz of some mid-Western conference center. And as for the galleries on the first three floors, they get the job done, but in a cramped and under-performing way.

James Gardner, formerly the architecture critic of the New York Sun, writes on the visual arts for several publications.