In 1691, British philosopher John Locke proposed that “the price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers.” His statement became the first commandment in the bible of modern business: Supply and demand drives everything. But at least in New York’s ultra-luxury condo market, Locke’s words are tough to come to terms with.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “The price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers.” — John Locke [/vision_pullquote]It’s easy enough to count supply, or number of listings. But quantifying demand becomes very tricky when faced with an increasingly global buyer pool. This creates a serious challenge for developers, who need to know how much they can sell individual units for to decide if doing a project is worthwhile. When the buyer pool was largely local, this was easy enough. But who today knows how many people around the world can afford an ultra-luxury apartment, and how many of them would be willing to buy one in New York?

This dilemma doesn’t just concern luxury developers but the whole industry. If developers are overestimating global demand for high-end New York product, they could be inflating a luxury bubble that could drag down the entire market. If they are underestimating it, the industry may well be misdirecting its resources.

With this much at stake, The Real Deal dove into the available data on supply and demand in the luxury sector. Be warned: The numbers come with several caveats, but they do provide a sense of where the market could go.

Fuzzy math

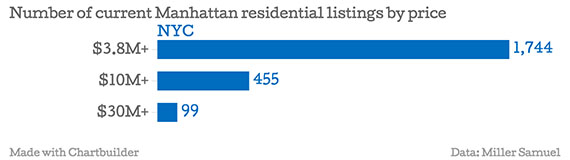

There are at least 99 single-residence listings priced at $30 million or more in Manhattan, according to New York real estate appraiser Jonathan Miller, a staggeringly high number by historical standards. And how many potential buyers for these pads are out there? “If they’re going to spend $30 million on a single asset, you’re really looking at someone who is a demi-billionaire,” said David Friedman, the president of Wealth-X, the global wealth data aggregator.

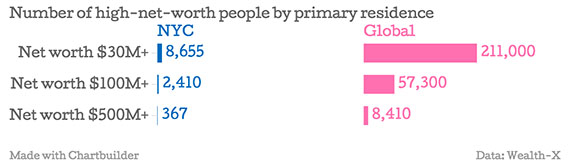

Wealth-X estimates there are 367 people worth half a billion dollars or more who own a primary residence in New York City, and 8,410 of these individuals across the globe (see chart below). Meaning, there is a potential buyer pool of up to 8,410 individuals for the 99 listings mentioned above. For developers to sell all these listings at or near asking price, at least 1.18 percent of the world’s demi-billionaires would have to be in the market for a $30-million apartment right now.

That’s a tall order, especially compared with the $10 million-plus price range.

According to Friedman, ultra-high-net-worth individuals (people with a net worth of $30 million or more) generally hold 13 percent of their net assets in owner-occupied luxury real estate.

By that reckoning, most buyers of units that cost $10 million or more likely have a net worth of at least $100 million. About 3,600 of these UHNWIs with a net worth of more than $100 million have a primary residence in New York City, while the global total stands at 57,300, according to Wealth-X. There are currently 455 listings at or above $10 million in Manhattan.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “If they’re going to spend $30 million on a single asset, you’re really looking at someone who is a demi-billionaire.” — David Friedman, Wealth-X [/vision_pullquote]This would mean around 0.8 percent of the world’s population of individuals worth $100 million or more would have to be apartment hunting in the Big Apple for supply in the $10 million-plus range to be met. That’s a more favorable ratio than for the $30 million-plus range. In other words, the data seems to indicate that developers would be better served building apartments at the lower end of the ultra-luxury market.

“Two million square feet, potentially, in the next few years is a little daunting,” HFZ Capital Group’s Ziel Feldman said at The Real Deal New Development Showcase and Forum in May, speaking of the volume of new ultra-luxury Units Being Built On 57th Street. Feldman is shying away from the highest price points, and is instead offering what he calls “affordable luxury.” At his latest High Line development, the Bjarke Ingels-designed 518 West 18th Street, Feldman is keeping apartments small, so that prices stay below $10 million despite a high rate per square foot.

Emily Beare, a top-producing luxury broker at CORE who currently has four listings above $20 million, said she sees continued strong demand for uber-luxury units. But she also argued that the demand-to-supply ratio may be more favorable for sellers at lower price points. “I think the $5 million and below range is where we’re seeing a little bit of a [listings] void,” she said.

Rules may not apply

There are several caveats to our analysis. Perhaps the most glaring one is this: Just because people can afford an apartment doesn’t mean they want to buy one. And according to Leonard Steinberg, president of Compass, buyers often break the rule that they shouldn’t invest too much of their wealth in a single asset.

“I would have been the first person to believe that,” he said, “but I was proven very wrong on many occasions. I’ve seen people whose financial statements were closer to $50 million spend half of that on a home.”

Steinberg offered other examples, such as individuals who aren’t UHNWIs but who receive an inheritance of $65 million and put as much of half of that into a single home.

And as for the number of people who qualify as UHNWIs, Steinberg thinks that number is probably much higher than Wealth-X’s estimate. The real question, he said, is who is actually interested in buying an ultra-pricey pad to begin with, and “no one knows the exact response to that.”

See and be seen

Why do people pay so much for apartments? One could imagine that many buyers with effectively bottomless pockets might feel perfectly at home in a middle-class millionaire apartment priced in the high seven or low eight figures (and Steinberg says many are). At the same time, both Steinberg and Friedman see steady demand for penthouse-in-the-clouds trophy homes in New York City.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “It’s almost as if there’s a new class of billionaires emerging in Manhattan. These are the uber-billionaires.” — Andrew Heiberger [/vision_pullquote]”They love this asset class,” Friedman said of the UHNWIs. “It’s part of their DNA to have unique, luxury, owner-occupied residences.” And with every month, the limits of luxury seem to be shifting. In January a penthouse at Extell’s condo tower One57 sold for $100.5 million – the highest price ever recorded in the city. Vornado’s nearby development 220 Central Park South could easily shatter that record. As The Real Deal recently reported, a Qatari buyer is looking to combine several units into a single $250 million mega penthouse.

“It’s almost as if there’s a new class of billionaires emerging in Manhattan,” said Town Residential’s co-founder and CEO Andrew Heiberger. “These are the uber-billionaires.”

“This is the second luxury asset class where we are seeing this trend, the first being the mega yachts,” he added. “The main difference is uber-luxury penthouses do not depreciate.”

And planting a stake in the most expensive apartment in your surrounding square mile may just be part of the natural trajectory of self-expression for the wealthy, with its final destination at the nearest benefit gala.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=”right”] “The general wealth display starts by first going out to fancy dinners,then buying fancy clothing, renting a fancy apartment, then buying a fancy apartment, then buying artwork, and then, getting into charity.” — Leonard Steinberg [/vision_pullquote]“The general wealth display starts by first going out to fancy dinners,” said Steinberg, “then buying fancy clothing, renting a fancy apartment, then buying a fancy apartment, then buying artwork, and then, getting into charity.”

But generalizations only go so far, as the buyer pool includes “a huge variety of cultures and a huge variety of levels of wealth and age of wealth,” he said. Additionally, buyers of ultra-luxury units can sometimes be a group of investors, such as at One 57’s $91.5 million “winter garden” penthouse.

In other words, data may help paint a better picture of the luxury market, but precisely quantifying demand remains out of reach. Despite its flaws though, the numbers conform with the observations of some market insiders: there appears to be too much supply in the uber-luxury segment compared to lower price ranges.

“I don’t think I have ever in my career seen such a disconnect between what is desperately needed built and what is being built,” Miller said. He argued that while demand for the most expensive units is strong, developers are “over-enthusiastically” building too many of them. Meanwhile, lower price points are being neglected, in part because the high cost of land often makes them unfeasible. The oversupply in the super-luxury market is “probably the world’s worst kept secret,” Miller added.