From the New York website: When General Electric executives phoned Blackstone Group’s Lexington Avenue office in March to propose one of the largest real estate deals in U.S. history, Kenneth Caplan’s first reaction was surprise.

“We were not expecting the call,” the global chief investment officer of Blackstone’s real estate group said. “They had been selling off parts [of their real estate holdings] and we had bought some smaller portfolios.” He assumed GE would continue to sell piecemeal, if at all. But GE had a very different plan: It wanted to sell its entire $26.5 billion property portfolio at once, and it wanted Blackstone to buy it.

A meeting at GE’s New York headquarters and a phone call to Wells Fargo later, Caplan and his colleagues began an “intense period of work.” On April 12, the parties announced a deal: Blackstone would buy $14 billion worth of GE’s properties and mortgages, Wells Fargo would buy $9 billion worth of loans, and other investors would cough up the rest.

In an industry where selling a single building can drag on for months or even years, Blackstone worked out a multibillion-dollar global portfolio acquisition in about three weeks.

“How many other players could have done [the GE deal]?” said Scott Rechler, head of real estate investment firm RXR Realty. “Over time, they have gotten into a size and scale where they can do deals few others can.”

GE Capital CEO Keith Sherin later said that he only had one potential buyer in mind. Caplan said that GE “came to us because they had confidence in us to get it done, and we got it done.”

The GE deal proved to any remaining skeptics that Blackstone’s real estate group is now in a world of its own.

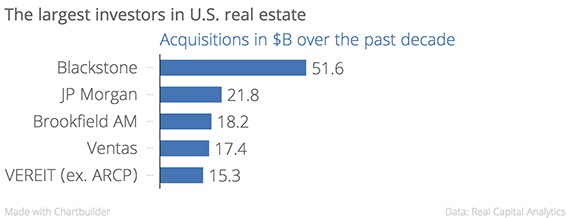

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “Over time, they have gotten into a size and scale where they can do deals few others can.” — RXR’s Scott Rechler [/vision_pullquote]With nearly $92 billion in assets under management¹, it is the world’s largest real estate investment manager and America’s biggest private landlord. It racked up average annual net returns of 18 percent over the past two decades, making its youthful head, Jonathan Gray, a cult-like figure whose every utterance is dissected in the media.

And its appetite keeps growing. Its latest $15.8 billion global fund is the largest in the company’s history. This raises the questions: Just how big can Blackstone’s real estate division get? And can anything slow it down?

The Real Deal took an in-depth look at the firm and its competitive landscape to find the answers.

From bit player to main attraction

Real estate is arguably Blackstone’s most impressive business. It’s tied with private equity as the largest of Blackstone’s divisions, accounting for $92 billion — that’s about 40 Empire State buildings — of its $333 billion in assets under management. And it represents about 60 percent of the firm’s total profits over the past two years.

But it wasn’t always so. Lehman Brothers veterans Stephen Schwarzman and Peter Peterson founded the company in 1985 as a private equity shop. It took them seven years to launch a real estate division. John Kukral, who joined the firm in 1994 and headed Blackstone’s real estate group from 2002 to 2005, said the company was much different in its early days. “There were only really four people in the real estate group,” Kukral, now CEO of Northwood Investors, recalled. “Nowadays it’s become a household name, but then it wasn’t.”

From left: John Kukral and Kenneth Caplan

The firm’s first real estate fund, launched in 1994, raised $400 million. Its second and third funds, in 1996 and 1999, raised $1.3 billion and $1.5 billion respectively.

“When Blackstone started the opportunistic (real estate) business, it was in the very early days,” said the head of a major real estate investment trust, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. The executive added that other fund managers like TPG and Carlyle Group didn’t start investing in high-risk real estate until later, which likely gave Blackstone a first-mover advantage in the field.

By the time the firm went public in 2007, real estate accounted for 22.5 percent of its total assets under management, still well behind corporate private equity, at 39.6 percent. The firm’s largest real estate fund at the time raised $5.5 billion.

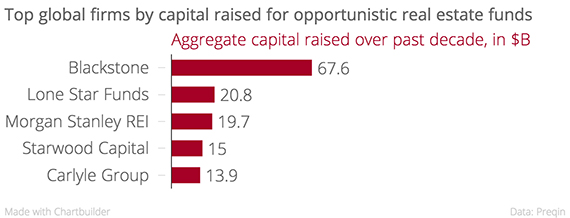

Fast forward to 2015, and Blackstone’s real estate division is tied with its private equity group in asset volume. The firm’s most recent real estate fund, raised in March, collected $15.8 billion from investors, and over the past decade, the real estate group raised more money than any of its private equity peers.

The aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis partly explains this ascent.

The aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis partly explains this ascent.

Real estate funds managed by Blackstone and its peers are opportunistic. They specialize in buying assets with a high upside and upgrading with an eye to selling them a few years down the road for fat profits.

The post-crisis climate was ripe for such deals. As the industry recoiled from high-stakes plays and embraced more risk-averse strategies, Blackstone boldly pushed new initiatives at an impressive scale.

In 2012, it created an entity called Invitation Homes, buying up nearly 50,000 single-family homes in areas rocked by the crisis, in order to renovate them and then rent them out.

Raising capital has also gotten easier. Bond-buying sprees by central banks around the globe depressed interest rates, which in turn pushed investors from bonds into comparatively high-yielding funds such as Blackstone’s.

Barry Sternlicht, head of private equity firm Starwood Capital Group, said at a recent NYU hospitality conference that he “raised large funds from investors that have kind of tossed in the towel” on fixed-income assets and are instead turning to real estate.

While many rival fund managers focus exclusively on real estate, Blackstone’s real estate group benefits from being part of a larger company with more diverse bets. Many investors in Blackstone’s real estate funds likely also hold stakes in its private equity or hedge funds, according to Morningstar analyst Stephen Ellis, who tracks the company. In this way, the real estate group gains from growth in Blackstone’s other divisions – and vice versa.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “We’re not going to lose your money.” John Kukral’s tongue-in-cheek pitch to clients [/vision_pullquote]It also likely bolstered Blackstone’s reputation that while its peers took body blows during the crisis, it emerged with only superficial wounds. The two real estate funds Blackstone raised in 2006 and 2007 still averaged annual returns in the low double digits between inception and late 2014, according to data from the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System.²

In late 2009, the company restructured its debt on Hilton Hotels, which it had bought just two years earlier. The stock had fallen by 70 percent, or almost $4 billion, since the acquisition, according to Bloomberg. Some said that Blackstone had made a rare misstep.

But Hilton’s spectacular stock rebound since prompted Bloomberg to recently anoint the deal “the best leveraged buyout ever.”

Kukral credits what he claims is Blackstone’s conservative investment strategy, adding that his half-joking pitch to clients before the crisis used to be: “We’re not going to lose your money.”

Although Blackstone dabbled in securitized debt, it never binged on junk bonds to the extent that rivals like Lehman Brothers did.

Gray matters

By the time Blackstone’s real estate business took off following the financial crisis, Kukral had already left to start Northwood. The replacement was his protégé, Jonathan Gray, who joined the firm straight out of college in 1992 and took over its real estate group in 2005 when he was only 35.

Gray, who declined to comment for this story, has done, by consensus, an excellent job of exploiting the post-crisis environment. “He’s a smart guy and he moves quickly,” said a top New York developer who spoke on the condition of anonymity, adding that the GE deal is a “terrific example” of his ability to quickly close on a whopper.

“I think they approach things with a sort of macro strategic perspective,” said RXR’s Rechler, who recently partnered with Blackstone on the $1.2 billion acquisition of the Helmsley Building at 230 Park Avenue and sold the firm a 50 percent stake in RXR’s New York office portfolio. “When they believe in something, they have strong conviction and can react quickly.”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “He [Gray] has a little bit of that Steve Jobs effect.” — Real Data Management’s Peter Boritz [/vision_pullquote]Invitation Homes, for example, sprouted out of Blackstone’s belief that the aftermath of the crisis coupled with long-term economic trends would increase demand for rental homes.

This bullish outlook on rentals extends to Manhattan. When Joseph Sitt’s Thor Equities backed out of an $800 million deal to buy a 25-building Manhattan rental portfolio from the Caiola family, Blackstone cut in and agreed to buy the buildings for a significantly lower price, about $700 million.

Its other recent large New York acquisitions include an office tower at 1740 Broadway for $605 million from Vornado Realty Trust and a $382.4 million deal for the retail mall and parking garage at the Sky View Parc complex in Flushing, Queens.

According to Gray, the firm tends to stay away from net-leased assets with low upside.

“Maybe it’s a Walgreens lease for 20 years,” he said at Blackstone’s annual investor day in 2014, “and you’re paying more than the value of the real estate – it’s being driven by fixed-income as opposed to growth in cash flow. We’re very cautious around stuff like that.”

Ground-up development opportunities are also largely ignored, he said, because “the risk-return tradeoff for development isn’t great.”

This strategy has paid off. Blackstone Real Estate Partners VII, a $13.5 billion global fund it raised in 2012, has generated annualized returns of 27 percent. The NCREIF Property Index, a benchmark composite that measures the performance of U.S. real estate held by investment managers like Blackstone, averaged returns of 11.2 percent during the same period.

This track record gives Gray a bit of an aura. He “has a little bit of that Steve Jobs effect, they [his peers] look at him as this visionary,” said Peter Boritz, head of commercial real estate software and advisory firm Real Data Management, which has been involved in a number of high-profile deals in Manhattan.

“You’d have to be a psychotherapist, I guess, to understand why he doesn’t need to grandstand at all, given his remarkable track record,” Blackstone co-founder Peterson said of Gray to the New York Observer in 2011, “but he doesn’t.”

Growth, interrupted

As Blackstone’s real estate group mushroomed, another factor behind its success became just as critical: sheer size.

Although Caplan dismissed the notion that his firm now enjoys a de-facto monopoly on $20 billion-plus deals, he admitted competition is scarce. “When you go back to the pre-crisis years, there was more competition in terms of large-scale opportunistic investments, and a lot of those competitors are no longer in existence,” he said. When Blackstone bought Equity Office Properties in 2007, it had to outbid a serious rival in Vornado. In this year’s GE deal, no one was breathing down its neck.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=”right”] Ever since Adam Smith published his treatise on pin manufacturers and the benefits of scale and specialization, economists have generally assumed that as far as companies go, bigger is better. [/vision_pullquote]“One thing that’s underappreciated is that when GE sold to Blackstone, the assets were geographically distributed,” said Morningstar’s Ellis. “There were assets in the U.S. and assets in Europe, and you need to have people on the ground.” Blackstone’s size, he said, allows it the personnel and infrastructure to act on a global scale, and its various funds and holdings give it more ways to profitably reposition properties. Caplan made a similar point, arguing that the firm couldn’t have pulled off the GE deal in 2007 because it didn’t yet have the means.

Blackstone’s size has become both a consequence of and a reason for its success. The more it outperforms its peers, the bigger it gets, the more access it has to gargantuan deals — often at a discount — that are beyond the reach of rivals, the more it outperforms them, the bigger it gets, and so on. It is easy to imagine this virtuous cycle of growth going on in perpetuity until Blackstone has devoured the entire real estate market – if there weren’t also some substantial drawbacks associated with rapid expansion.

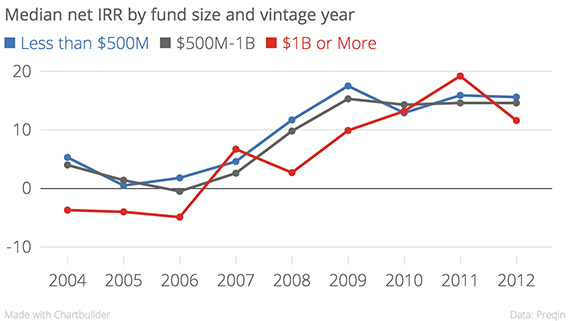

Ever since Adam Smith published his treatise on pin manufacturers and the benefits of scale and specialization, economists have generally assumed that as far as companies go, bigger is better. And yet, studies have found that in certain cases smaller firms tend to outperform their larger peers. This appears to be the case for investment funds, at least.

A 2004 paper in the American Economic Review by economists Joseph Chen, Harrison Hong, Ming Huang and Jeffrey Kubik found “strong evidence” that smaller mutual funds (funds that invest largely in stocks) tend to outperform their larger peers. The same seems to go for private real estate funds, according to data from research firm Preqin (see chart below).

The Economic Review paper argues that larger funds are subject to “organizational diseconomies”: The bigger they get, the more layers of management are usually involved, the greater the potential for conflicts and delays that drag down returns. A second possible explanation is that smaller players often have a higher tolerance for risk, which can lead to higher returns — at least in good times.

The Economic Review paper argues that larger funds are subject to “organizational diseconomies”: The bigger they get, the more layers of management are usually involved, the greater the potential for conflicts and delays that drag down returns. A second possible explanation is that smaller players often have a higher tolerance for risk, which can lead to higher returns — at least in good times.

On both counts, Blackstone appears to have done well, largely because it operates and takes risks as if it were a smaller fund manager, according to observers. A developer who spoke on the condition of anonymity said Gray has an “entrepreneurial” way of doing things that’s atypical of industry giants.

“He makes his investment decisions rather quickly,” the developer said. “It’s not done by committee and with layers of checks and balances.”

Kukral agreed. “That’s a credit to Steve Schwarzman’s management style,” he said. “He hires smart people and he lets them run their business.”

The firm’s speed was on display in 2007, when Gray outbid Vornado — Steve Roth remains rueful about the missed opportunity — to buy the Equity Office portfolio for $39 billion. By all measures, the eve of the 2008 financial crisis was probably the worst time to buy office buildings. But on the day Blackstone closed on the deal, it flipped the New York properties to Harry Macklowe in a $7 billion transaction that proved his undoing.

Another challenge that comes with growth is growing interest from regulators. A securities lawyer who spoke with TRD on condition of anonymity said the Securities and Exchange Commission is zeroing in on what it deems inadequate fee disclosures among private real estate funds. “Part of what the SEC has done is use enforcement cases as a way to shape best practices in the industry,” the lawyer said. In other words: rather than write new rules, it prosecutes what it believes to be bad behavior in order to pressure others to change tack. In May, Blackstone announced that the SEC “informally” asked about the firm’s practice of collecting fees when it takes a company in its portfolio public.

“We are in discussions with the SEC regarding a potential resolution of these matters,” Blackstone said in its most recent quarterly regulatory filing. It added that the firm in 2014 “voluntarily modified” its fee practices in response to an SEC review.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “You’d have to be a psychotherapist, I guess, to understand why he doesn’t need to grandstand at all, given his remarkable track record.” — Blackstone’s co-founder Peter Peterson [/vision_pullquote]Last year, the U.S. Justice Department began investigating whether Blackstone and investment banks including Goldman Sachs and Credit Suisse paid bribes to secure sovereign wealth investment.

Another regulatory push that could cut into Blackstone’s profits are plans to get rid of the so-called carried interest loophole. Carried interest, or the share (usually 20 percent) of a fund’s profit that fund managers like Blackstone retain, is currently subject to capital gains tax — as opposed to the much higher income tax. Several leading presidential candidates are looking to change that. Hillary Clinton has vowed to close the loophole, while Donald Trump recently said that fund managers are “getting away with murder” by not paying income tax on carried interest. But the push seems unlikely to pass Congress due to Republican opposition.

Perhaps most challenging is a fourth dilemma associated with size: Blackstone has more capital available than ever before to invest in real estate, at precisely the time when it is becoming tougher to find the type of undervalued assets the firm specializes in. It is tricky enough to find the niche deals in New York City or London that generate double-digit returns if you have $50 million to invest. Now imagine having to spend $15 billion.

Stephen Schwarzman, apparently riding the 6 train (credit: Blackstone via Twitter)

“I think the challenge could be at times, are there enough opportunities?” Rechler said.

Caplan acknowledged that distressed properties in the U.S. aren’t as abundant as they were a few years ago, but said the firm’s global focus — it is using part of a $8 billion fund to buy up properties in crisis-stricken southern Europe and raised a $5 billion Asia-focused fund — helps it keep up returns even as the domestic market matures. On Wednesday, Christopher Heady, Blackstone’s head of real estate for Asia, told the Wall Street Journal the firm is scouring for properties in top-tier Chinese cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, amid volatility in China’s economy.

Its latest $15.8 billion global fund underscores that optimism: Its target return is 20 percent – lower than the 27 percent achieved by its prior fund but still above its 18 percent average over the past two decades.

“I think by definition each successive fund can’t always be bigger,” the aforementioned REIT head said, and added that Blackstone had sustained its growth by offering new products.

For example, it is looking to ramp up investment in low-risk, core-plus real estate with a target return of between 10 and 12 percent. “The core-plus asset class is about three times the size of what we’re doing in the opportunity class,” Schwarzman said in an earnings call last year, adding that the company could well add $100 billion worth of core-plus assets within the decade.

Morningstar’s Ellis shares this optimism. “It’s going to be harder to find deals, but at the same time, the real estate market is just massive, so Blackstone is really a very small piece,” he said. “They can still find a lot of ways to put money to work.”

¹Figures as of June 30, 2015

²The New York State Teachers’ Retirement System was an investor in both those funds.