The Federal Reserve is likely to raise short-term interest rates later this year for the first time since 2006. Will it throttle the commercial real estate boom? That’s a multibillion-dollar question for investors.

Real estate insiders talk about the rate hike the way doctors talk about wine: healthy in moderate doses. Even if higher rates increase the cost of borrowing, the argument goes, they reflect an improving economy, which should boost rental income and, in turn, property values.

So no reason to worry? Not quite.

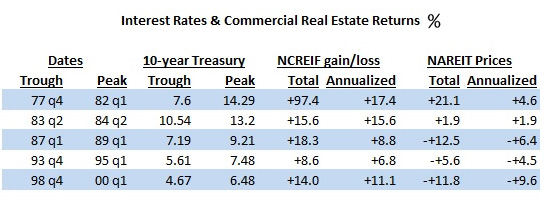

At a speech at the Yale Alumni Real Estate Association’s national conference last week, Blackstone Group’s real estate COO Kathleen McCarthy argued that historically, rising interest rates have coincided with rising property values. The data McCarthy and other optimists point to is shown below (courtesy of Forbes). Five times over the past few decades, interest rates (measured as 10-year treasury bond yields) hit a nadir and then rose noticeably. In all these cases, the NCREIF National Property Index (a benchmark for commercial real estate yields) showed positive returns while interest rates rose.

(credit: Forbes.com)

But let’s revisit a basic observation: commercial real estate markets move in cycles that can only last so long. All other things being equal, if real estate prices have been rising nonstop for nine years, they are generally more likely to fall soon than if they have been rising for only three years.

Which suggests that it does matter when in the real estate cycle the Fed decides to raise rates. And some are now worried that low interest rates have inflated real estate values for too long, and that a rate hike could hasten – and possibly worsen – a market downturn bound to happen anyway. Historically, this situation has little precedent.

A page from history

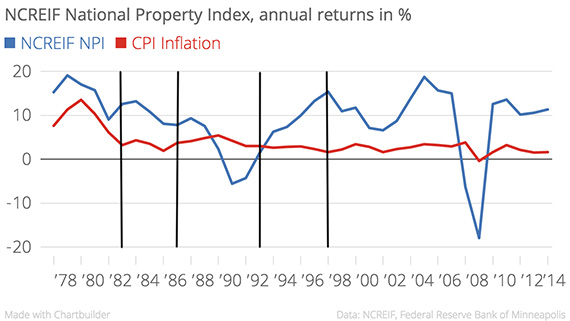

The chart below shows the NCREIF National Property Index (NPI) annual returns. The vertical black lines mark the points when interest rates hit a low and then began to rise. A large and growing gap between real estate returns and inflation signals a booming property market. If real returns fall below zero, the market is in trouble – as happened around 1990 and 2008.

If the Fed raises rates at the end of this year, it will do so after five years of continuously rising prices. Most previous rate hikes cited by McCarthy and others, however, took place at much earlier points in real estate market cycles — i.e. before such a sustained period of price growth.

In 1983 and 1986, real estate returns had only just begun rebounding from lengthy declines, and in 1993 the market was on the mend after a serious crisis. In such situations, you would expect the real estate market to keep growing – provided the rate hike is gradual enough. After all, the industry was just picking up steam.

In 1998, the shift from low to high interest rates took place after a lengthy boom. What followed? A decline in real estate returns.

To sum up: if you account for the timing of a rate hike, history’s lessons are far less reassuring.

There are caveats to this data. The NCREIF NPI, which includes both property appreciation and income, is an imperfect measure of prices. And long-term bond yields (which matter most to real estate) don’t always respond in the same way to a rise in short-term rates. At the very least though, the numbers question the claim that rising interest rates will be good for real estate prices.

A matter of context

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=”right”] If you account for the timing of a rate hike, history’s lessons are far less reassuring. [/vision_pullquote]With history offering little guidance, how can we predict the impact of a rate hike? One way is to distinguish between properties that stand to benefit most from an improving economy (of which rising rates are a symptom), and those that have more to lose from rising borrowing costs and shrinking spreads between real estate and bonds.

Observers reckon the bulk of the U.S. commercial real estate market falls into the former category. “What are real estate values driven by? They’re driven by cash-flow growth,” Coburn Packard, who heads Apollo Management’s real estate equity business, said at the Yale conference. “As the economy continues to grow, if that translates to improving fundamentals, real estate should do well.”

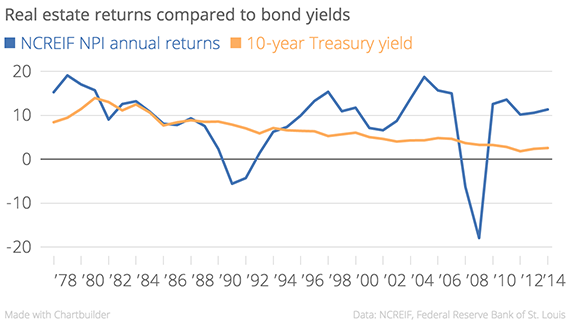

The real estate industry as a whole is far less leveraged today than it was prior to 2008, meaning a rise in borrowing costs is less likely to damage. And spreads between US commercial real estate returns and government bonds are historically high (see chart below). Even if bond yields rise a bit they are unlikely to dramatically change the equation and deter real estate investors.

But for New York and a handful of other large cities, the picture looks less rosy. Here, prices for trophy commercial properties have grown so quickly that they are now largely speculative and have less of a connection to underlying fundamentals. This means rising rates could do considerable damage. “There is a disequilibrium in a lot of gateway cities driven by big-liquidity folks,” Packard said. “These markets will not react well to a rising-rate environment.”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “There is a disequilibrium in a lot of gateway cities driven by big-liquidity folks. These markets will not react well to a rising-rate environment.” — Coburn Packard, Apollo Management [/vision_pullquote]Class-A office cap rates in Manhattan average 4.2 percent, according to Real Capital Analytics – down from 5.3 percent in 2010. For investors seeking safe assets, these low returns may still look attractive. But if yields on the much safer 10-year treasury bonds rise noticeably from a current 2.08 percent, many Manhattan office buildings, hotels and luxury retail condos will suddenly look, at today’s prices, like a terrible deal.

“If you can buy a treasury (bond) with a ten-year duration and earn 5 or 6 percent,” Packard added, “or you can buy an office building with capital needs every time a lease rolls and earn 3 percent – what would you do?”