Years before famously defaulting on $4.4 billion in loans, Tishman Speyer and BlackRock Realty had lofty ambitions for America’s most famous housing complex — Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village.

In the months leading up to the $5.4 billion purchase in 2006, the joint venture partnership received an intriguing offering memo from sellers MetLife.

That document, now available for download on TRData, detailed how a buyer could collect gargantuan revenue from the 110-building complex, mostly by converting stabilized units and tossing them onto the market. How much, you ask? Read on to find out.

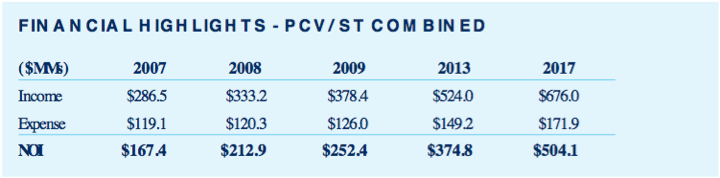

The offering memo from MetLife and CBRE touted the “infinite opportunities to personalize, improve and transform the complex into the city’s most prominent market rate master community,” and projected that net operating income would reach $504.1 million in 2017.

Of course, those opportunities turned out not to be so infinite.

At the time, Stuy Town’s sellers were projecting a rent stabilization rate of less than 30 percent at the complex by 2018. Today, more than half of the complex’s 11,241 apartments remain under some form of rent regulation, and per agreements with new owners Blackstone Group and Ivanhoé Cambridge, 5,000 units (44 percent) will remain stabilized for at least 20 more years.

The now-obsolete rent destabilization target from 2006 may in part explain the expected $504 million in projected NOI in the memo, 156 percent more than what Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village netted in just the last fiscal year — $197.1 million, according to a report from Trepp.

The story is now well known. The new owners were unsuccessful in converting as many units for high-end occupancy as they had anticipated, and Stuy Town lost significant value. Despite all of that, Blackstone Group and Ivanhoe Cambridge went into contract last month for the nearly same amount the complex sold for almost 10 years ago, when Tishman Speyer and BlackRock won their $5.4 billion bid.

The 2006 Stuy Town offering memo also includes a short statement regarding air rights, a big question mark looming over the current deal. The document cites “an array of income-producing structures” that could be built at Stuy Town, such as retail and parking, and mentions the possibility of demolishing one of the residential towers, in which case “air rights could be applied to the creation of additional units in a newly constructed building.”

The possibility of condo conversions is discussed in the memo, something a partnership between Brookfield Asset Management and Stuy Town tenants floated back in 2011, but was ultimately unsuccessful in winning. Another mentioned measure is major capital improvements (MCI), or unit improvement expenditures that could be legally passed on to stabilized tenants.

In 2014, the Stuy-Town Tenants Association reached an agreement with post-default complex manager CW Capital to reduce the tenant MCI burden by up to $30 million over the next decade.