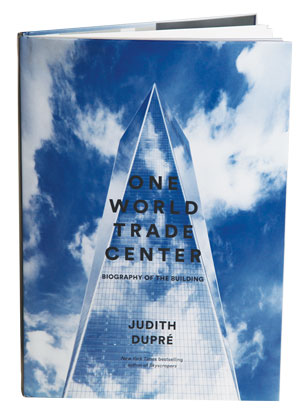

Judith Dupré’s new work, “One World Trade Center: Biography of a Building,” is a substantial tome masquerading as a coffee-table book. Its size, weight and format all conspire to suggest that this is just another pretty architecture book, when in fact, it is the product of a copious amount of research and dozens of interviews with key players involved in the construction of the tallest building in the western hemisphere.

The coffee-table aesthetic is thanks, of course, to the abundance of full-page glossy images of the titular building — in whole and in close-up detail — as well as moodily spectacular images of the Manhattan skyline. No true citizens of the five boroughs will be able to look at these images without a twinge of pride or without hearing, in the back of their minds, the swelling strains of Gershwin.

But the 284-page book is about more than just the building from which its title is taken. In fact, it provides an extensive review of the entire development of the World Trade Center site, as well as adjacent buildings, like Seven World Trade Center. That building, like its taller neighbor One World Trade, was also designed by mega architecture firm Skidmore Owings and Merrill, which is headed by architect David Childs.

Dupré’s prose, much like the featured images, is entirely in the nature of celebration. Although the author presents her writing in exhaustive detail, she is less interested in seeking out villains or philistines than in extoling the evolution of the World Trade Center site as we find it today.

Even players who appeared to be opponents — like architects Daniel Libeskind, who conceived of the original tower, and Childs, who took over to redesign the building after Libeskind was essentially pushed out— are presented in equally glowing terms.

The various turf wars between Larry Silverstein and the WTC landowner, the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, and between former Governor George Pataki and the competing (and often incompatible) claims of the victims’ families and the authorities tasked with completing the project, all seem to fade away in the warm celebratory glow that frames the book.

Nonetheless, as long as readers are aware of the uncritical assessment Dupré provides then the book will not disappoint.

Dupré, the author of the best-selling 2008 book “Skyscrapers: A History or the World’s Most Extraordinary Buildings,” was given “unfettered access” to the WTC site team and the Port Authority’s archives, according to her publishing house Little, Brown and Company. And her book is especially strong in its coverage of the design and engineering of the building, from its glass curtain wall and concrete base to its seven-ton glass and stainless-steel beacon, 1,776 feet above the city.

Dupré, the author of the best-selling 2008 book “Skyscrapers: A History or the World’s Most Extraordinary Buildings,” was given “unfettered access” to the WTC site team and the Port Authority’s archives, according to her publishing house Little, Brown and Company. And her book is especially strong in its coverage of the design and engineering of the building, from its glass curtain wall and concrete base to its seven-ton glass and stainless-steel beacon, 1,776 feet above the city.

Similar attention to detail will be found in her discussion of other landmarks on the WTC site, including architect Michael Arad’s 9/11 Memorial, Snøhetta’s 9/11 Memorial Museum, Santiago Calatrava’s recently opened PATH train station dubbed the Oculus and the St. Nicholas National Shrine, which recently broke ground. One might have wished, however, for an equal amount of scrutiny devoted to the designs of Towers 2, 3 and 4.

If there is one major criticism to be made of this book, it is only of a typographical nature. Because this volume largely presents itself as a coffee-table book, the main text is often, and confusingly, interrupted by sidebars and digressions. Some of these, however, can be quite rewarding, like the 16-page timeline of the redevelopment of the World Trade Center site.

In any case, the book richly confirms the evidence that is increasingly available at the World Trade Center site itself — that the rebuilding exceeded expectations.

Nearly 15 years ago, when the redevelopment of the site was first contemplated, and in the years that followed, there was so much clamorous confusion and so many unyielding stakeholders, that we would have had every right to expect that the resulting design would be an unmitigated disaster. Or at best, and in true Manhattan spirit, the paltriest of compromises.

But that has not happened. The structures there, whether they are completed or still being built, have been conceived in a plurality of styles, but they all harmonize remarkably well. Each of these individual projects has remained true to itself but has also rejected the “vanguardism at all costs” that spoils so much contemporary architecture. And, just as important as the design, each of them seems to be remarkably well made, especially by Manhattan standards. There is no evidence of value engineering, the besetting sin of most construction in the five boroughs. The entire design and development community of New York City has achieved a remarkable thing, and Dupré’s book goes a long way to describing how — against all the odds — that result could ever have come to pass.