For many Catholics, the sweeping decision made by church officials to merge about 40 parishes in New York City came as a tough blow. Come summer, when the restructurings plans are finalized, families that have worshipped in one place for generations will now have to head elsewhere on Sunday mornings.

But putting the emotional impact aside, the move could put a variety of religious buildings in coveted neighborhoods in play, potentially creating huge upside for the real-estate industry, analysts said.

“A lot of these are prime sites,” said Steve Schleider, president of Metropolitan Valuation Services, which has appraised church sites in the city. “The church could easily monetize these assets, either through ground leases or outright sales.”

To be sure, not every church is expected to be sold; While some will close, many will be kept and used for special occasions like church anniversary celebrations, according to archdiocese officials.

But some parishes that struggle to keep the lights on, or have put off expensive repairs, say, will probably unload superfluous properties like convents and rectories, officials note. The parishes would keep the proceeds from those sales, though some owe the archdiocese millions of dollars for support through the years.

At the same time, a handful of parishes are fighting the order to merge, even as parishioners admit that their properties — many of which are in densely settled areas that have few buildable lots — are extremely valuable.

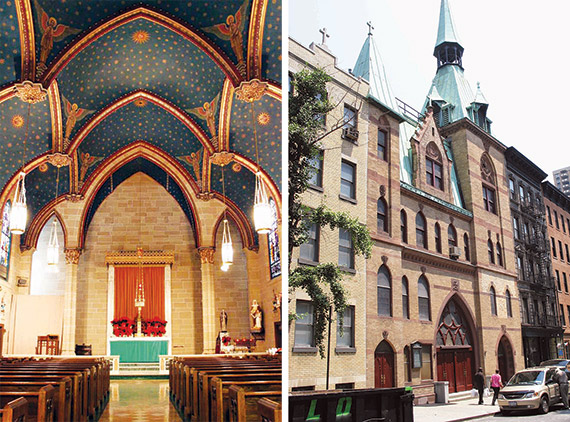

“Yes, it’s true, developers would probably love to grab this site,” said Janice Dooner Lynch, a real estate lawyer and longtime parishioner at Our Lady of Peace on East 62nd Street, near Second Avenue, in Midtown East, which is slated to merge with St. John the Evangelist on East 55th Street.

Our Lady of Peace on East 62nd Street is slated to merge with St. John the Evangelist nearby.

The facade of the neighborhood church is landmarked, but that likely won’t deter developers, if it goes up for sale.

The church building for the former, a red-brick 1866 neo-Gothic structure where Lynch’s grandparents were married in 1922, is located in the Treadwell Farm historic district. Adjacent to it is a well-kept four-story rectory that resembles a row house, on a block lined with many elegant versions of them.

And while the two buildings’ facades are landmarked (as is the case with a few other churches on the list), that might not be a deal breaker for developers.

In fact, in 1983, the landmarked Church of the Holy Communion, an Episcopal complex on the Avenue of the Americas in Chelsea, morphed into the dance club called the Limelight, thus becoming one of the first major ecclesiastical properties to get a makeover in the city.

“I thought that was the craziest thing, that a church could turn into a disco,” Lynch said. “But nothing shocks me anymore.”

After a checkered two decades including drug raids and a grisly murder involving a “Club Kid” and a dealer known to frequent the Limelight, the club was shut down by police. Several attempts at reopening, including under another name, failed, and it closed for good in 2007. In 2010, it became home to the Limelight Marketplace, a collection of shops, and this past fall, part of it was converted to a David Barton Gym.

That high-profile case aside, most repurposed churches in the city, Catholic or otherwise, have become apartments. But Our Lady of Peace is not handing the keys to condo developers just yet. Its parish has officially appealed to Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who heads the Archdiocese of New York, the ecclesiastical authority that ordered the consolidation. The opponents submitted a 2,000-name petition opposing the planned merger, Lynch said.

The Archdiocese of New York covers Manhattan, Staten Island and the Bronx, as well as seven upstate counties. There are about 750,000 parishioners in the three boroughs, church officials said.

But only about a third of that number regularly attend mass, according to officials, and the numbers have declined sharply over the years, which has produced a surplus of space, though some parishes dispute that math. Church officials have also blamed a shortage of priests for the mergers and closures.

At St. Lucy’s, on East 104th Street in East Harlem, for example, the congregation of 700 represents a recent uptick, according to the pastor, Monsignor Oscar Aquino.

Still, a school that was once housed in the church structure, a cream-colored stucco-sided mid-block building near First Avenue, encountered dwindling enrollment and merged about a decade ago with one run by St. Francis de Sales, on East 96th Street, Aquino said. Ultimately, even the combined school shuttered.

St. Lucy’s, which is to join St. Ann’s parish on East 110th Street, has in recent years rented out its former classrooms to a tutorial service that works with students who need extra help. But that business pays only $4,200 a month, not nearly enough for the upkeep of the entire 1915 building, said Aquino, who added that the parish also has an outstanding debt to the archdiocese of $200,000 for a boiler replaced several years ago.

The church, which includes a red-brick four-story Italianate rectory, is located in a gradually gentrifying area, as luxury developers push northward from the Upper East Side.

But if a decision is made to sell any of the buildings, Aquino hopes his congregation benefits: “You have to respect the will of the people. The church belongs to them.”

Kal Chany, a three-decade parishioner at St. Elizabeth of Hungary on East 83rd Street on the Upper East Side, which is scheduled to merge with St. Monica on East 79th Street, understands real estate pressure. He has watched as projects have gobbled up nearby buildings in step with the construction of the new Second Avenue subway line.

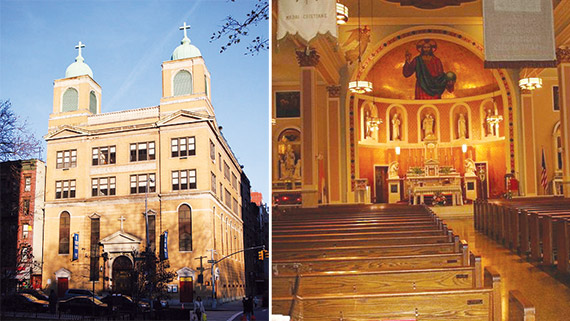

St. Elizabeth of Hungary on East 83rd St. (photos above) is slated to merge with St. Monica four blocks south.

But his parish, which caters to the deaf community, recently completed a $250,000 renovation and actually has cash still in reserve, a sign Chany said means it should stand on its own. Besides, “some of the people who will be moving to this neighborhood once the subway is completed will be Catholics who need a place to go to church,” he added.

How much these church sites may be worth depends on several factors, including landmark status, zoning — most churches are not built to the maximum of what can go on a parcel, brokers say — and any deed restrictions about how the site can be reused.

For example, bars were banned at site of the former St. Vincent de Paul Church on North Sixth Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which closed in 2005.

Redeveloped by Heritage Equity Partners, its block-through campus now contains high-end apartments; 10 are in the one-time rectory and 39 in the remodeled church itself. And 55 units are now being added to a former Catholic school.

Of course, location is perhaps the most significant determiner of value.

To wit: A property like the Church of the Nativity on Second Avenue in the trendy East Village, which is supposed to merge with the nearby Church of the Most Holy Redeemer on East Third Street, for instance, would likely fetch far more than the Church of St. Roch in the working class Port Richmond section of Staten Island, which is to join the Church of St. Adalbert.

In general, a 50-by-100-foot property that is generously zoned with a floor-to-area-ratio of 10 and with a church that could be razed — a possible scenario for some sites on the Upper East Side — could be worth $40 million, assuming a land price of $800 a square foot, Schleider said.

Of course, several factors could cut into that amount — for example, if a not-for-profit group renting space on the property had to be bought out of its lease, Schleider explained, adding that every site is unique. But the most prime addresses could still command “multiples of tens of millions of dollars,” he added.

Not every church is protesting its reorganization. One example is St. Joseph’s, a six-story yellow-brick church and rectory at the corner of Monroe and Catherine streets in Chinatown that is set to merge with the Church of the Transfiguration, on Mott Street in Chinatown.

St. Joseph’s in Chinatown (photos above) is slated to merge with the Church of the Transfiguration a few blocks away. The parish already has another church, St. James, that was combined in an earlier reorganization.

The building, topped with a pair of verdigris domes, can fit more than 1,000 people, but rarely has more than a few hundred at a time, said the Rev. Lino Gonsalves, its pastor. The last Sunday masses will be held in July. He added that about eight administrators are expected to lose their jobs.

“We have a lot of property,” he added, mentioning St. James church, a landmarked Greek Revival edifice at 32 James Street that merged with St. Joseph several years ago after a fire. The parish’s portfolio also includes a three-story rectory behind St. James at 21 Oliver Street. “If you are a Donald Trump, maybe you could buy the whole thing,” Gonsalves said.

For its part, the archdiocese, which spends a total of about $40 million a year supporting some of its churches, says the potential windfall from selling properties was not a top concern when figuring out which parishes to merge. The idea instead, said Joseph Zwilling, a spokesman, was to make each parish more self-sufficient.

Zwilling said the process played out democratically, with input from parishes, and not rashly, as Cardinal Dolan began undertaking the process soon after being appointed in 2009. But some parishes say they were never consulted.

Catholic Church properties that have changed hands in recent years include St. Ann’s on East 12th Street, near Fourth Avenue, which made room for a New York University dorm, though its facade was preserved; and Mary Help of Christians, a few blocks away on East 12th Street, which was razed to make way for an apartment building developed by Steiner NYC.

On the other hand, St. Vincent de Paul on West 23rd Street in Chelsea, which was tapped for closure under a previous downsizing effort, has sued to stop that from happening. The suit is still active.

Still, for the most recent batch of churches, “we have deliberately not made any plans to sell any of these properties,” Zwilling said. “It is human nature to speculate. But that is not a road that we have begun to travel yet.”

Some brokers agree. “I’m sure they will take their time,” said Bob Knakal, the chairman of Massey Knakal Realty Services, a commercial firm that has sold buildings on behalf of the archdiocese before. “They are very deliberate and very disciplined.” TRD