When a Chinese buyer scooped up a $70 million co-op at the Sherry-Netherland, the deal was a Herculean effort, and not just because the original asking price was $95 million. The March 2015 transaction marked the first time the co-op board of the iconic building on Fifth Avenue allowed a foreign buyer to join its ranks.

When a Chinese buyer scooped up a $70 million co-op at the Sherry-Netherland, the deal was a Herculean effort, and not just because the original asking price was $95 million. The March 2015 transaction marked the first time the co-op board of the iconic building on Fifth Avenue allowed a foreign buyer to join its ranks.

While New York City’s notoriously exclusive co-ops have been taking steps to increase their marketability for several years now — whether it be by adding gyms or renovating common spaces — in the last six to 12 months, they’ve ramped up their efforts in new ways.

Not long after the Sherry-Netherland sale, the board of the Pierre, which sits one block north, quietly signaled to brokers that it, too, would consider a well-qualified foreign purchaser.

“Everyone stopped and said, ‘Here’s a co-op that has done quite well by that shareholder. Can we mimic that?’” said Stan Ponte of Sotheby’s International Realty, who specializes in high-end Manhattan co-ops.

And the Pierre was not the only one. Some other high-end co-ops, such as River House on East 52nd Street and 898 Park Avenue, have also loosened their rules.

That may be because although co-ops still represent the lion’s share of New York’s residential market, a recent dip in sales has taken a toll on the sector.

That may be because although co-ops still represent the lion’s share of New York’s residential market, a recent dip in sales has taken a toll on the sector.

In 2015, there were only 6,805 co-op sales — down 11 percent year over year, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel. Condo sales, on the other hand, rose 2 percent to 5,150 during the same time.

“The people that you would imagine who can afford everything, they want to be on the 60th floor with sweeping views of the George Washington Bridge,” said Douglas Elliman’s Richard Steinberg, describing the allure of soaring new condo towers.

Co-op boards, said Steinberg and others, are looking to stay competitive as condos increasingly eat into their market share.

Some boards are appealing to buyers with more lenient construction and renovation rules or financial requirements, according to attorney Eva Talel, the head of the co-op and condo board group at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan.

Some boards are appealing to buyers with more lenient construction and renovation rules or financial requirements, according to attorney Eva Talel, the head of the co-op and condo board group at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan.

But not all boards are rushing to overhaul the rules.

While a slew of high-end co-ops are opening up a bit, the toniest Manhattan buildings don’t see any reason to. To the contrary. Many co-op boards became emboldened by the recession, said Aaron Shmulewitz, head of the co-op and condo practice at the Manhattan-based law firm Belkin Burden Wenig & Goldman.

“Lots of co-op boards took the position of, ‘We’re healthy because we have been so restrictive,’” he said.

In fact, during the financial crisis many condos mimicked co-ops and looked more carefully at buyers, particularly those whose wealth was tied to large stock portfolios.

But even while not all co-op boards are chasing condo prices, they still want to maintain their market value. “They want the resale prices in their buildings to be at or ahead of the [rest of the] co-op market,” said Shmulewitz. “Co-op and condos are just two completely different markets.”

Financing freedom

The biggest change reverberating around the residential market is that some co-ops are allowing financing for the first time.

Last year, the co-op board of the River House — which in 2014 turned away the French ambassador to the U.S. — bit the bullet.

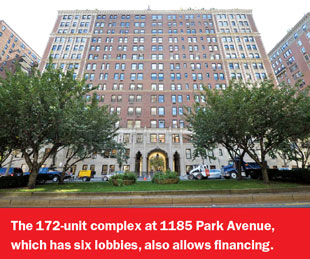

Six months ago, 898 Park Avenue, a Romanesque building with just 15 apartments, followed suit, allowing up to 40 percent financing. Buildings such as 1021 Park Avenue and 1185 Park Avenue, the 172-unit complex with an interior court, driveway and six lobbies, now allow financing as well.

Six months ago, 898 Park Avenue, a Romanesque building with just 15 apartments, followed suit, allowing up to 40 percent financing. Buildings such as 1021 Park Avenue and 1185 Park Avenue, the 172-unit complex with an interior court, driveway and six lobbies, now allow financing as well.

Sotheby’s Ponte said financing restrictions were designed to keep unqualified buyers at bay. Easing those rules, not surprisingly, has increased demand.

“For co-ops that require 100 percent cash, well, that reduces your buyer base,” said Ponte. “That reduces demand, which in turn can reduce value.”

Although the changes are recent, co-ops have been feeling a pinch from the condo market for some time. But the current influx of high-priced condos — roughly 6,500 hit the Manhattan market in 2015 — has widened the gulf between the two markets.

While Manhattan prices have reached record highs, those gains are largely thanks to condos.

The median co-op price was $755,000 in 2015 — a 2 percent jump from 2014 and a 12 percent increase from 2006. Those gains pale in comparison to the condo market, which had a median price of $1.52 million in 2015, up nearly 13 percent year over year and up a whopping 52 percent from a decade earlier.

“These [changes] are all reactions to the surge in demand and the price increase in condominiums,” Steinberg said. “Co-ops have to be proactive now. They have to be on equal footing. They’re seeing these huge numbers that people are paying for condos and they’re saying, ‘Why aren’t we getting these prices?’”

Kathy Braddock, co-managing director of William Raveis NYC, told The Real Deal last year that co-ops on Park and Fifth avenues “used to be a place where families went, especially if you were well-heeled.” That’s no longer the case, she said.

Kirk Wallack, whose eponymous firm manages 65 city apartment buildings, said one of his Park Avenue co-ops, where apartments go for $4 million to $5 million, changed its policy three months ago to permit up to 50 percent financing from zero.

“It was a shareholder who had been there a long time who asked the board to consider it. The board reviewed it and agreed it was time to do it,” he said.

According to Wallack, co-op boards are considering simple economics.

“At this particular time, in my opinion, the upper end of the market has come to a standstill,” he said. “Buildings that did not [allow] financing before are looking at it now to see if, in fact, they should permit it so that they can be more competitive,” he said.

Buyer identities

Despite the Chinese buyer’s $70 million deal at the Sherry, co-op boards have historically eschewed foreign buyers.

“Remember, it’s a co-op. You own shares that entitle you to live in the apartment. If one person stops paying and all their money is in some other country, how do you effectively get that money?” Ponte said.

Boards that now welcome foreign buyers, he said, are still focused on making sure the buyer has significant assets in the U.S.

Boards that now welcome foreign buyers, he said, are still focused on making sure the buyer has significant assets in the U.S.

For domestic buyers, many co-ops have permitted acquisitions through a trust since the 1980s, and within the past year or so, some boards have become receptive to buyers purchasing apartments through limited liability corporations and family limited partnerships.

Shmulewitz said they permit such transactions only with safeguards in place, such as occupancy and transfer restrictions.

Of course, time seemingly stands still at certain grand buildings that have not made changes, such as 834 Fifth Avenue, 740 Park Avenue and 820 Park Avenue.

“Co-op boards feel that they’re there to keep the barbarians outside the gate, to not let bad people or people with bad finances into their co-ops, and thus keep all their shareholders’ finances secure,” Shmulewitz said.

“Co-op boards feel that they’re there to keep the barbarians outside the gate, to not let bad people or people with bad finances into their co-ops, and thus keep all their shareholders’ finances secure,” Shmulewitz said.

Of course, many of those “barbarians” want nothing to do with the rigors of dealing with a co-op board anyway.

Melanie Siben, an agent at Rutenberg Realty, had a client who put it this way: “He said he’d rather have surgery without anesthesia than subject himself to a snotty co-op board.”

Renovating space

No matter the address, the majority of co-ops have in the last two to three years installed gyms, roof decks and gardens where possible — allowing boards to raise property values and quality of life for a relatively low cost.

Rutenberg’s Siben said 220 Madison Avenue, a 198-unit co-op in Midtown South, has replaced its elevators and updated the hallways and the roof deck. And at 200 Central Park South — a co-op whose values have risen thanks to its proximity to condo towers like One57 and 220 Central Park South — the board approved a new gym, roof deck, package room and garden in recent years.

“Shareholders know they’re living a few feet away from neighbors who swim with unlimited amenities,” said Siben, who lives in the building, “and no co-op in that neighborhood wants to be seen as the old lady on the block.”