It was one of many signs last year that a growing number of New York City condo developers are on borrowed time.

Bank OZK had committed $108 million to finance a 92-unit condo building at 615 10th Avenue back in 2015. But last April, with the project stalled, the construction lender dialed that back by $20 million, forcing the developer to grab a lifeline from mezzanine lender Mack Real Estate Credit Strategies.

The troubles brewing at that Hell’s Kitchen project are playing out across Manhattan as condo developers run out of extensions on their construction loans. With billions of dollars in debt coming due over the next few years, and sales in the doldrums for the foreseeable future, developers are under increasing pressure from lenders to slash prices or convert to rentals to generate cash.

Many developers are resorting to short-term, high-interest inventory loans in the hope of waiting out the slump, sources say. But the oversupply of high-end units, new state taxes, a drop in overseas buyers and renewed fears of a pied-à-terre tax suggest that debt collectors may come calling before new buyers do.

“For luxury condos, it’s a perfect storm of bad things,” said Andrew Heiberger, who founded Citi Habitats and now-defunct Town Residential. He said many listings are still overpriced, and the market has been hurt by fewer foreign buyers, the SALT and mansion taxes and oversupply.

“Additionally, many developers are going to have a hard time with velocity and selling enough units to cover their debt service,” Heiberger said.

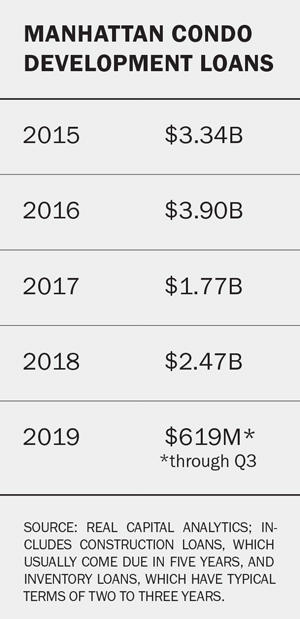

Since 2015, condo developers have borrowed more than $12 billion for projects in Manhattan alone, according to data firm Real Capital Analytics, though some of that debt may have since been paid down, the company said.

Over that same period, RCA’s data shows, more than 8,000 new Manhattan condo units were built or announced, creating an inventory glut that’s now weighing heavily on the luxury market. In the third quarter of 2019, there were 1,951 luxury units on the market, a jump in inventory of 33 percent over the same period in 2018, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel.

Manhattan condo development loans reached a peak of $3.9 billion in 2016 but dipped to $1.77 billion the next year, while 2019 is expected to mark a new low point, with less than $630 million in financing booked by the end of September, according to RCA (see table).

Manhattan condo development loans reached a peak of $3.9 billion in 2016 but dipped to $1.77 billion the next year, while 2019 is expected to mark a new low point, with less than $630 million in financing booked by the end of September, according to RCA (see table).

Most construction loans have three-year terms plus two one-year extensions, according to bankers, so much of the $7.24 billion that developers borrowed in 2015 and 2016 will be coming due over the next two years. And any inventory loans — which typically have terms of two to three years — will have to be paid back even sooner, increasing pressure on developers.

“The activity is not what everybody had hoped for,” said Andy Gerringer, a managing director with the new development advisory firm Marketing Directors.

Gerringer said banks have been calling him over the last few weeks asking what kinds of rents unsold condos can fetch.“This is the next step, to try to get some kind of cash flow coming in,” he said. “I think it will be very interesting what happens next.”

Converting to rentals creates immediate cash, but it makes developers wait much longer to recoup their investment, so most resist the move as long as possible.

Instead, developers are rolling out increasingly extravagant incentives and amenities to woo buyers. Five months after offering to waive common charges for up to 10 years at One Manhattan Square, Gary Barnett’s Extell Development launched a rent-to-own program in September for the 815-unit tower at 225 Cherry Street, allowing tenants to apply a full year’s rent toward the purchase of a unit, which amounts to a discount of nearly 4 percent.

And Broad Street Development recently made headlines with its offer of in-home IV therapy drips at its 61-unit building at 40 Bleecker Street.

But nobody expects nutrient-infused IVs to get luxury condo sales off life support.

As of mid-December, 278 contracts had been signed for units priced $4 million and above in 2019, versus 415 for the same period in 2018, according to brokerage Olshan Realty. That drop comes after years of relative stability. There were 429 signed contracts in the same period in 2017 and 427 in 2016, per Olshan.

The bleak sales outlook is leading bankers to lean harder on developers to find ways to move inventory or generate cash flow.

“Lenders are becoming more impatient because they want their loans paid back,” said Andy Singer, CEO of the Singer & Bassuk Organization, which arranges financing for developers. “There’s lots of tension.”

Rowdy partners

Increasingly, that tension is among the developers themselves.

Developer Ian Bruce Eichner faced an ugly legal battle for control of the 83-unit condo tower at 45 East 22nd Street in Flatiron, which he built with cash from preferred-equity players Dune Real Estate Partners and Fortress Investment Group, as he resisted their pressure to slash prices.

Only an 11th-hour inventory loan of $168 million from Madison Realty Capital in June 2018 saved Eichner from defaulting and losing control of the project.

Such struggles within joint ventures are becoming more common as partners with different timelines face conflicting incentives when juggling slow sales and debt payments.

The developers behind the ultra-luxe 82-story tower next to the Museum of Modern Art at 53 West 53rd Street — a team including Hines, Goldman Sachs and Singapore’s Pontiac Land Group — had to resort to arbitration early last year over how deeply to discount its slow-selling units.

The $860 million in construction financing they secured from Singapore’s United Overseas Bank Limited in 2014 is coming due, and Hines wanted to slash prices at the Jean Nouvel-designed building. But Goldman and Pontiac — with deeper pockets to wait out the slump — wanted smaller discounts.

The average list price for the 64 apartments for sale as of Dec. 13 was $3,600 per square foot, putting them firmly in the hard-to-trade territory of $3,000-plus per foot, brokers say.

A spokesperson for the project declined to comment or make developers available for an interview.

Such high-priced units became even harder to move last year after taxes went up on luxury homes. In July, not only did transfer taxes increase, but the mansion tax expanded. Before the change, that levy was a flat 1 percent on all homes priced at $1 million or more. But now that 1 percent applies only to homes priced from $1 million to $2 million, and pricier homes pay higher rates on a sliding scale — up to 3.9 percent for $25 million-plus properties.

Still, developers are resisting steep discounts for fear of setting off a downward spiral, according to a lender who asked to remain anonymous because he originates loans to many condo developers.

“What we are hearing is that developers are trying to hold the line at 10 percent to 12 percent off their current ask,” the lender said. “Everybody is trying to avoid the impression of desperation and a fire sale.”

Buzzworthy discounts

Few of the current crop of luxury projects caused more buzz when it launched than the condo conversion of the upper floors of the Woolworth Building, the iconic 58-story 1913 skyscraper at 2 Park Place.

Few of the current crop of luxury projects caused more buzz when it launched than the condo conversion of the upper floors of the Woolworth Building, the iconic 58-story 1913 skyscraper at 2 Park Place.

But the Woolworth Tower Residences also provided one of the more buzzworthy discounts among ultra-luxe condos when the five-story unfinished penthouse — dubbed the Pinnacle — was reduced last fall from to $79 million from $110 million, a discount of more than 28 percent.

The project has limped along since sales launched in 2014, with just 10 of its 32 units sold, according to public filings.

Nonetheless, the developers have so far managed to keep discounts on the remaining unsold units from breaching the 10 percent threshold, according to Ken Horn, founder of Alchemy Properties, who is developing the project along with BlackRock Private Equity Partners.

Horn downplays the burden of the unsold units’ carrying costs — common charges plus loan interest — and said he has paid off about 70 percent of his $220 million construction loan from United Overseas Bank.

“We feel no financial pressure to dump these units,” Horn said.

Other developers, however, are feeling the heat from their bankers to unload inventory, and it’s rankling their brokers.

Aby Rosen’s RFR Realty and Chinese firm Vanke, developers of the 96-unit, 63-story condo at 100 East 53rd Street, appear to have resorted to slashing prices as they labor under a mountain of debt — including $360 million secured from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China before Chinese firms began pulling back investment.

For example, unit 45A, a two-bedroom, was listed this winter at $4.95 million, down from $8 million in 2016 — a 38 percent discount.

As of Dec. 13, just 23 of the property’s units had closed, according to public filings, and 12 of those were recently listed as rentals on StreetEasy.com. Such quick-turnaround rentals can be a sign that investors are snapping up units in bulk, according to lawyers and lenders, suggesting deep price cuts.

The building’s brokers admit to feeling pressed, but deny any sense of desperation.

“I don’t think there’s a single new development building that has not come under pressure from banks,” said Leonard Steinberg, the Compass agent directing sales. “But it’s not like there’s a gun to our heads.”

Lenders just need to sit tight, Steinberg insisted.

“You need to put on your big-boy pants,” he said. “This market requires a different level of patience.”

Running out of gas

Some developers may be able to rely on the tender mercies of indulgent lenders, at least for a while.

Tessler Developments has propped up its sagging 69-unit condo building at 172 Madison Avenue with a succession of loans from the same bank.

The developer secured a high-leverage construction loan of $141 million from Deutsche Bank in 2014, which amounted to roughly 88 percent of the project’s total projected cost of $160 million, according to boutique advisory firm Maverick Capital, which arranged the financing.

But since it began marketing in 2015, the 33-story development at the edge of the NoMad neighborhood has cycled through four sales teams: Keller Williams, Corcoran and Compass — twice — sometimes because the brokers threw up their hands.

In 2017, with construction still not complete, Tessler secured a $164 million inventory loan from Deutsche Bank and private equity firm TPG. At the time, about 43 units were under contract, according to the marketing team.

Fast-forward to 2018 and the sales team had changed again, but the sales figures hadn’t budged. Tessler got another bailout, in the form of yet another partial inventory loan from Deutsche Bank — this time for $94.5 million — to retire the 2017 debt.

Since then, only a few more units have sold, with 47 units having closed by mid-December, according to public filings.

Most of the remaining apartments are listed for around $2,600 per square foot. But nearly a third of the project’s planned $321 million sellout total seems to rely on the unfinished penthouse. The five-level, 20,000-square-foot aerie with 11 bedrooms, a pool and up to 23-foot ceilings is listed at $98 million — or $4,900 per square foot — making it the most expensive new unit on the market.

Whether Deutsche Bank will quadruple down on its bet with Tessler in the current sales climate remains to be seen. But the German bank — famous for continuing to lend to the Trump Organization for years after most other banks stepped back — is known for taking risks in the service of increasing its American market share.

Calls and emails to Tessler CEO Yitzchak Tessler went unreturned.

Other lenders are more conservative about continuing to bankroll the luxury condo sector, but bankers are not hitting the panic button yet. It’s for a reason, however, that developers don’t want to hear: Values remain about 1.5 times the equity in most projects, according to lenders, so there’s still room for prices to come down before loans are imperiled.

For example, one of the top construction lenders in New York, Bank OZK, has 26 outstanding loans to condo-only projects, with a total commitment of $2.95 billion. But its chair, George Gleason, told TRD that the bank’s exposure is no cause for worry. The average weighted loan basis per square foot is just $989 — well below the asking price of even discounted luxe units.

Gleason said that of the 61 loans his bank has made in New York City for projects that include condominiums, 31 have been paid off. Some of those were made whole through late-stage inventory loans, he said, but he declined to provide a list, citing company policy.

Bank OZK did ratchet back its support for the 615 10th Avenue project, rising on the site of a former Hess gas station, but Gleason is confident its remaining investment is safe.

“They did have some issues, but they have addressed those issues,” he said.

In 2017, the project’s original developer, Xinyuan Real Estate, handed over management of the project to Kuafu Properties, which negotiated an extension until 2021 for the truncated OZK loan.

For now, the developers are standing by their offering plan promising a $165 million sellout, and expect to price units at about $2,000 per square foot when — or if — sales eventually begin, according to a source close to the project.

Kuafu did not return a call for comment, but the source said the project could still make money — if not as a condo, then as a rental property.

“We think the project is very viable,” the source said. “The rental market there is on fire.”