Modular construction is gaining ground in New York City, but its future here may be determined on distant shores. That’s because after several projects made with locally built modules, the next building, a hotel in Williamsburg, will be constructed with units made in Poland.

Outsourcing construction overseas is a surprising shift, and some skeptics question the logic behind it. But if the experiment is a success, the Williamsburg Pod Hotel could turn modular construction in the city on its head, even as some in the industry were hoping that rising interest could be a boon to homegrown companies making the units.

The city’s first modular building, the Stack, opened in Inwood in early 2014. Its prefabricated modules were built by DeLuxe Building Systems in Berwick, Pennsylvania, a town southwest of Scranton, about two-and-a-half hours away from the 28-unit rental building.

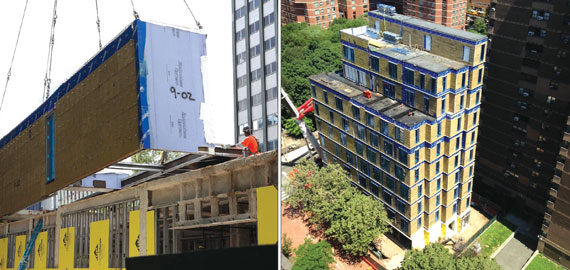

In late June, Monadnock Development finished stacking the city’s second modular building, Carmel Place in Kips Bay. The 55 units that make up the micro-apartment building (previously called My Micro NY) were made by Capsys Corp., a Brooklyn Navy Yard-based manufacturer that shares a founder, Nicholas Lembo, with Monadnock. The building, slated to open in December, cost $300-to-$400 per square foot to build, according to Tobias Oriwol, project developer at Monadnock.

The Stack

And in Brooklyn, construction of Forest City Ratner’s Tower B2 in Pacific Park, which is slated to be the tallest modular building in the world at 32 stories, got back on track in recent months, after suffering severe delays due to a dispute between its lead contractor and the developer. In a twist, Forest City took over the modular production facility, also at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, from the contractor, Skanska, and established a new subsidiary to run it, FC Modular. In June, the developer hired Susan Hayes, a veteran construction executive, to head the new venture.

From certain angles, the momentum of Brooklyn-based modular construction appears strong. The method is seen by many as fueling a symbiotic relationship between local manufacturing; union labor (which has started a new branch to adapt to the two-tiered process) and developers, who stand to benefit from dramatic reductions in building time and costs.

“I’m a staunch advocate of local production. I think that local production reinforces the relationship between design and production. It reinforces the relationship between the local building community and what they are seeing built around them,” said Jim Garrison, principal of Garrison Architects. “That’s the ideal.”

Given that view, it seems contradictory that the Garrison Architects-designed, 255-room Pod Hotel that CB Developers and Ironstate Development plan to build in Williamsburg will be crafted with modules imported from a town more than 4,000 miles away, in the north of Poland.

Attitudes across the industry run the gamut from apprehension to outright disbelief.

“I was very shocked to see that,” said Robby Kullman, general manager of Capsys. “They found a way, I guess, to ship it.”

Craig Rosenman, director of acquisitions at the Daten Group, which recently finished three modular rental buildings in White Plains, said he would never consider importing modules, due to a combination of shipping costs, the difficulty supervising production, and concerns about meeting local codes and passing inspections. “It wasn’t really a thought in our minds.”

Why Poland?

Charles Blaichman, owner of CB Developers, said the Polish company he selected for the Pod Hotel, Polcom Modular, won the contract after impressing him with a pitch that proved a thorough understanding of the luxury hotel product he needed. Pod Hotels offer small rooms at what is billed as “budget” prices (about $220 to $275 per night), but emphasize design, amenities and modern connectivity.

Polcom has built CitizenM hotels in London and Amsterdam and is reportedly being considered by Brack Capital Real Estate to supply modules for a planned CitizenM hotel on the Bowery. Brack directed inquiries to a representative for CitizenM, which said it was too early to comment.

Blaichman was concerned by the constraints of U.S. companies, which tend to be small and limited in their product selection. For example, Rosenman said that only certain companies manufacture wood modular units rather than steel, and of those, few can do a multi-family style project. For a specific luxury product like the Pod Hotel, sources agreed there is little competition stateside.

“The American companies we were dealing with were really having a hard time grasping it, because they had never done this level of high-end finishes in their projects,” Blaichman said.

Blaichman ruled out his Northeastern options, and almost settled on a modular company in Indiana, before switching to Polcom “at the eleventh hour,” he said. “It was cheaper to transport from Poland by boat than to do it by truck from Indiana.”

Potential drawbacks

Architects and developers who have worked on projects using local or semi-local modular production often worry about oversight, both in terms of design and city building standards.

“Personally, I found it very important to be close to the factory as a designer,” said Eric Bunge of nArchitects, the designer of Carmel Place, which won a design competition held by the Bloomberg Administration to build the city’s first “micro apartments.”

Bunge said he visited the Capsys factory on a weekly basis during production. These regular inspections let him catch mistakes early in the construction process that fewer visits might have missed. That saved the project from larger setbacks that may have been costly.

“You have more control and precision,” Bunge said. “You develop a rapport with them.”

Daten Group’s Rosenman seconded the importance of factory visits. “You’re going through and you’re punchlisting out the work, just like you would if they were building it on site,” he said.

Patricia Lancaster, former commissioner of the Department of Buildings, said that New York City codes are among the most stringent, partially due to the city’s density. That means that things like fire safety standards get taken up a notch. “You’d want familiarity with the city and how it does business,” when going through the inspection process, she said.

Jack Dooley, the U.S. director of Polcom, acknowledged that adhering to local standards in the various countries the company supplies to — everywhere from Singapore to Canada — is “not an easy feat by any means.” Each region, and often different regions within the same country, has its own list of acceptable accrediting agencies. The inspectors hired for the Pod Hotel project are Americans who travel to Poland as many times as necessary.

Garrison said he had already been to Poland twice by mid-July, and planned to go roughly once a month during production. He admitted that grappling with building standards like fire codes is a challenge with overseas production, but ultimately thought it could be overcome.

“You can organize your way into a reasonable situation with this,” he said. “I don’t really have anxieties about that.”

Kullman, of Capsys, said, however, that the inspection process is not the biggest problem. “I think shipping is.”

In the long term, Polcom would prefer to set up a production plant in the U.S., and has looked at several East Coast locations, including the Brooklyn Navy Yard. “At this stage we are testing the market,” said managing director Luke Slominski. “We need to make sure that there are enough projects to keep the factory busy.”

Modules made in Brooklyn are put in place for Carmel Place, the micro-apartment project in Kips Bay

The wage question

Blaichman did not cite lower wage rates in Poland as a boon to his balance sheet, but the cost of labor is certainly a concern in the debate over importing modules.

Richard Lambeck, chair of the construction management program at NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate, said that while he is optimistic about the situation Forest City has worked out with unions, “That’s not to say that people won’t be very creative and say ‘let’s go to China,’ like we have for curtain walls and steel and everything else,” he said. “People feel like they can build it cheaper in China.”

Barry Hersh, a professor of real estate at the Schack Institute, also said that he doesn’t see Poland as the place developers will flock if they decide to take advantage of overseas production en masse. “The wage rates in Poland are lower than the U.S., but they are not as low as other parts of the world,” he said.

Polcom’s Dooley said that the cost of employing skilled laborers like welders in Poland and the U.S. is very comparable, whereas there is a “significant difference” between wages for simple installers in the two countries.

With land costs in New York City spiraling ever upward, Lambeck said importing modules could be particularly appealing to developers of affordable housing. “Land is going to be a fixed cost,” he said. “How are you going to save on the construction side?”

The potential for successful importing also puts the potential for American modules becoming an export in jeopardy, observers said.

Modules as U.S. export

Forest City Ratner CEO MaryAnne Gilmartin bore the brunt of growing pains for New York City-based modular with the problems related to Skanska and Tower B2. Construction on the tower stalled from August 2014 until March as Forest City and Skanska sued each other over the project plans and execution, including alleged misalignment of some of the modules that were already stacked.

MaryAnne Gilmartin

But Gilmartin came up swinging, and is looking for ways to export FC Modular’s product in the future.

In June, at TerraCRG’s One Brooklyn Summit, Gilmartin said that part of her successful pitch to get construction unions on board with modular was explaining that the units could someday be exported.

Asked to elaborate last month, Gilmartin said that right now she is focused on finishing the Pacific Park building. “With that said, FC Modular is a business and we are of course looking to see what the possibilities are for the future,” she added.

Some peers find the concept mind-boggling.

Monadnock’s Oriwol said the benefits of using a producer in the city are local knowledge and decreased transportation costs, but the product cost is undeniably higher.

“It’s not that Capsys is expensive, it’s just that New York is expensive,” he said. “So I don’t think the export market from here is that viable.”

Rosenman agreed, saying that when Daten Group compared the cost of buying from New York City to buying from other Northeastern manufacturers, it determined that time was the only thing saved.

Of a potential New York City-based export industry, Rosenman said, “They have to pay New York City labor rates even for their factory workers. So I don’t truly understand how that model makes sense.”

And even Kullman said that aside from very specialized products (Capsys once exported classrooms on wheels to Venezuela, complete with Spanish-language learning materials), he doesn’t understand who would buy from the U.S.

In March, Capsys’ space at the Navy Yard will be taken over by Steiner Studios, and it is still looking for its next home, which will likely be outside the city. At that point, FC Modular will have a corner on the New York City-based modular industry, complete with a location that couldn’t be more convenient for shipping — at least for the time being.

Former Buildings Commissioner Lancaster, for one, has great faith in Hayes, a longtime friend, to make strides as FC Modular’s new chief. “She’ll take it worldwide,” Lancaster said.

And why not? While Bunge doesn’t like the idea of working with imported product, he has no qualms about exporting his designs. “We can send things to the moon. Why can’t we send them across the ocean?”