Trending

NYC’s new global investment fix

The Chinese pullback and rising interest rates led to a slow few years, but the city’s commercial market may stand to gain from today’s international tensions

More than half a year after China imposed strict capital controls, the country’s nearly $1 trillion sovereign wealth fund reportedly struck a deal to invest in a prime Times Square office tower.

China Investment Corporation’s bid for a 49 percent stake in 1515 Broadway — home to Viacom’s world headquarters and the famed Minskoff Theater, where “The Lion King” performs — valued SL Green’s 54-story asset at nearly $2 billion in the summer of 2017. And the sovereign wealth fund appeared to have narrowly edged out its competitors, including the Munich-based insurance giant Allianz.

“We provided a quote, and then we were told that we were not the winning bidder,” Christoph Donner, Allianz Real Estate of America’s CEO, recalled.

But then China’s fund, which had been operating without a chairman since February, began to dial back its dealings, and the German investor got a second chance.

“Throughout the summer, there was some noise in the market, and we had an opening to come back in,” Donner said. “And being the reliable investor that we are, we were able to provide a relatively short time frame to close … and were able to execute on that.”

Allianz bought a 43 percent stake in the 1.9 million-square-foot tower that fall in a deal that made it one of the country’s most valuable buildings at the time.

The German investor followed up its Time Square investment with two more on Manhattan’s West Side. It nabbed a roughly 30 percent stake in L&L Holding and Normandy Real Estate’s $900 million Terminal Stores warehouse late last year. Then this summer, Allianz bought a 49 percent stake in WarnerMedia’s office condominium at Related Companies’ 30 Hudson Yards in a sale-leaseback that valued the 26-floor chunk of the building at a whopping $2.2 billion.

Meanwhile, China’s CIC — which shelled out big bucks for stakes in One New York Plaza and the former McGraw-Hill Building at 1221 Sixth Avenue in 2016 — has not done any deals in the city since its bid for 1515 Broadway fell through.

“I don’t think we’ll ever see another wave of money that comes in so fast and goes out so fast,” said Marcus & Millichap associate broker Eric Anton about the broader sea change in Chinese investment in New York City. “The Japanese in the ’80s took a decade to deploy and a decade to recede. This was more like three years in and three years out, so it’s quite incredible.”

Related: The foreign buyer fallout

At the same time, a strong U.S. dollar, volatile interest rates and other macroeconomic factors helped dampen foreign investment in the city to the benefit of other markets in the U.S. and around the world. The 10-year Treasury climbed as high as 3.2 percent in 2018, and European and Korean investors, in particular, faced mounting costs pegged to currency hedging as a result, said CBRE’s Bill Shanahan.

“The market today is very different than what it was two years ago,” the veteran investment sales broker noted. “When the Chinese started pulling back, interest rates were very low and then started to rise. That pushed a lot of [other] people out of the market.”

Now, as interest rates decline and recession fears mount, commercial property investors around the globe are getting caught up in a whirlwind of shifting economic and geopolitical tides that could alter the playing field once again. In the thick of Washington’s trade war with China and other countries, growing uncertainty around Brexit, civil unrest in Hong Kong and political crises elsewhere in the world, all eyes are on the New York City market.

But while some investors have managed to uncover opportunities in the five boroughs in the midst of the turmoil, others have decided to wait it out.

“Whenever you have the headlines every week, every day about trade wars with China, immigration, tax reform and a lot of sweeping changes in the works, that just has a negative impact on consumer confidence,” said Pierre Debbas, a founder and managing partner of the boutique real estate law firm Romer Debbas.

“I meet with a lot of potential clients from overseas, and you get the sense that they’re just going to wait it out,” he added. “They’re a little worried about political stability and don’t mind seeing how the next election goes.”

Foreign buyers in flux

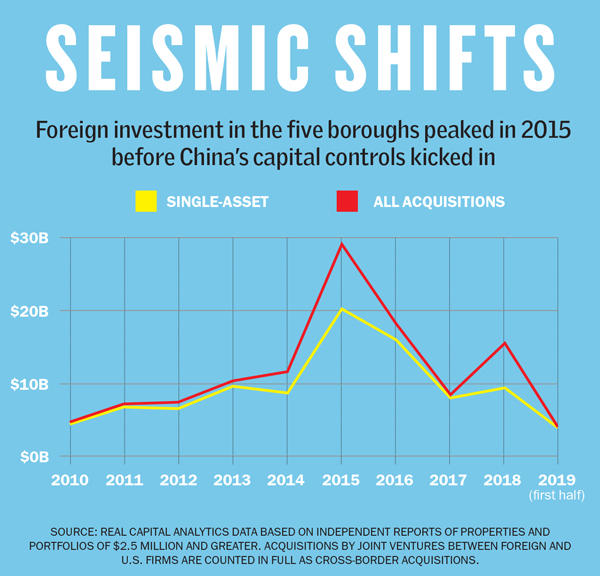

Excluding mergers and portfolio deals, cross-border investment in the Big Apple has dropped off noticeably since the boom years, according to data from Real Capital Analytics.

Foreign buyers acquired just under $8 billion worth of commercial property in the five boroughs in 2017 and $9.5 billion last year, down from about $20.2 billion in 2015 and $15.8 billion in 2016.

“Ultimately, there’s really no way to get back to where investment was in 2015 and 2016 without a significant Chinese presence,” said Moody’s Analytics director Adam Kamins.

As Chinese capital continues to recede, though, a new foreign investment landscape has emerged with a diverse mix of other cross-border players.

With its big-ticket Manhattan acquisitions, Allianz may have emerged as the top foreign investor in New York’s commercial market since 2017. But Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management is the other contender, depending on how you slice the numbers.

Brookfield was by far the largest buyer of real estate in the Big Apple from July 2017 through June 2019, with $7.5 billion worth of deals involving more than 50 commercial properties, according to RCA’s data. The catch: Those numbers include Brookfield’s $6.8 billion acquisition of Forest City Realty Trust, which propelled it to become the city’s largest commercial landlord.

“Individual asset sales are the bedrock of the market. That’s where pricing signals come from [and] where you get the temperature of the market,” said RCA Senior Vice President Jim Costello.

“If someone is buying a company to get at the real estate assets, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they like all the markets they’re exposed to,” he added.

Related: Planting flags in the Big Apple

Narrowing down the data to single-asset deals only, Allianz comes out on top. But Brookfield lands high on that ranking as well, taking the No. 2 spot.

The firm’s standout single-asset deal in 2018 was its $1.29 billion acquisition of the ground lease at Kushner Companies’ troubled 666 Fifth Avenue with an option to buy.

That deal prompted the Qatari government — which owns a 9 percent stake in Brookfield through its sovereign wealth fund — to “reconsider” its investment strategy in light of Jared Kushner’s ties to the president and Saudi royalty, Reuters reported in February.

Outside of Allianz and Brookfield, most cross-border investors were involved in just one or two deals in NYC over the past two years. Other top buyers in this period included pension funds from Canada, Australia and the Netherlands, sovereign wealth funds from Norway, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates and private players like Japan’s SoftBank, South Korea’s Daishin Securities and Switzerland’s UBS.

“The Canadians and the Germans are really the two groups that are most active in the [New York City] market,” Shanahan said. “And really it’s Allianz that’s a big deal for the Germans.”

Learning to let go

While Donald Trump’s trade war has yet to take a visible toll on cross-border investment in New York City, the larger economic picture is still shaking out.

“I think all of us are increasingly worried about where the trade war is going,” said Kamins, who pointed to other concerns beyond China — including last year’s trade tensions between the U.S. and Canada.

A split between the two countries would seriously impact cross-border investment in New York and other major markets, he noted.

“Those are the kinds of tensions that I think are the biggest short-term existential risks,” Kamins said.

As cross-border acquisitions have slowed, meanwhile, sales of New York commercial properties by foreign investors have continued at roughly the same rate, RCA’s data shows. And some previous big-time buyers are finding themselves on the other side of the negotiating table.

After dishing out $467.5 million in cash to scoop up 685 Third Avenue — its sixth property in the city — in late 2017, for instance, Tokyo-based Unizo Holdings reversed course and began selling off various properties.

Until just recently, the company was facing a hostile takeover bid from the Japanese travel agency H.I.S., while New York-based Fortress Investment Group, which is now owned by SoftBank, has made a less aggressive buyout offer.

The winding down of Unizo’s $1.3 billion New York City portfolio comes amid a “capital recycling program” that includes the sale of commercial assets in Washington, D.C., and Tokyo as well, according to the company. Unizo told analysts in May that “it’s difficult to acquire properties that meet our criteria in Japan and the United States.”

“At this point, we cannot comment on whether or not we will sell our remaining assets in New York” a spokesperson for Unizo said in an email to TRD.

But perhaps no trade involving a foreign owner was as striking the Abu Dhabi Investment Council’s 80 percent discount on its sale of the Chrysler Building in April, after the property’s ground rent more than quadrupled in a market-rate reset.

The iconic skyscraper attracted the attention of another foreign investor, though, with the Austrian real estate firm Signa Holding making the property its first U.S. investment, in partnership with Aby Rosen’s RFR Holding.

And under China’s capital controls, several firms that once seemed destined to take over the city’s trophy real estate market — including the beleaguered Anbang Insurance Group and HNA — continue to shed many of the outsized investments they made during the boom.

“We’re advising many of the large and medium-sized Chinese companies that came over,” said Marcus & Millichap’s Anton. “In certain instances, they can’t sell, for any number of reasons, or they’re in the middle of a project and just need additional capital.”

His firm recently brokered a deal to restructure the joint venture behind the long-stalled development at 520 Fifth Avenue, which saw partners Ceruzzi Properties and Shanghai Municipal Investment take a back seat to New York-based Rabina Properties.

“There’s every conceivable type of story out there, given the amount of deals that were made in those few years,” Anton said about the sea change in Chinese investment.

Even with the decline in cross-border deals in recent years, sources say New York’s commercial real estate market remains one of the world’s most active.

“The U.S., and New York in particular, is a very large investment market, and by no means were the Chinese the only investors,” Allianz Real Estate’s Donner said. “It’s not like they went away and all of a sudden you had a big gap that needed to be filled. I don’t think the Chinese disappearing has dramatically changed the market.”

Currency conundrums

One of the key differences between domestic and cross-border investment is currency risk, sources say.

Foreign investors will often try to hedge against that risk by trading in currency forwards or futures, which brings interest rates into the equation as well.

In recent years, the strong dollar and rising rates in the U.S. have caused currency hedging costs to surge for many European and Asian investors, leading them to seek out alternative destinations for their capital.

That could even drive more American real estate investors to seek opportunities in other countries, sources say.

“A strong dollar means it’s hard to make money on the currency side,” said Michael Rotchford, capital markets co-head at the London-based commercial brokerage Savills. On the flip side, he noted, “we’re recommending to some of our U.S. clients that they should be looking overseas at some of the real estate assets there, because it’s actually very favorable from that perspective.”

Though U.S. buyers have been enjoying historically low interest rates, “they’re not that low relative to other countries,” Rotchford added.

The European Central Bank’s main refinancing rate has been at zero since early 2016, while the Bank of Japan’s key short-term interest rate has remained at negative 0.1 percent over the same period.

“A quarter of the world’s government bonds are at negative yields right now,” said JLL global capital group head Riaz Cassum. “So a lot of investors who may have bought Treasuries or German bunds are looking elsewhere for cash flow. And real estate — specifically U.S. real estate — is a really attractive option for them.”

Currency considerations pushing investors away from New York have also led to a surge of interest in London office properties, despite (or perhaps because of) the looming threat of Brexit. That comes as the value of the pound has plummeted relative to the dollar and Euro.

“Some of the buyers are buying in London despite the political uncertainty surrounding Brexit, because they actually think it’s a good currency arbitration opportunity,” Cassum said.

The British capital has emerged as a prime target for South Korean investors in particular. Last year, South Korean investment in the city’s office properties ballooned to $3.3 billion — eight times the prior year’s volume. Nearly half of that came from the Korean National Pension Service’s buy and leaseback of Goldman Sachs’ new London headquarters, Plumtree Court.

But a number of other big London sales to Korean investors have stalled amid the uncertainty of Brexit, while other Korean buyers have found themselves saddled with London office properties they are unable to fully syndicate to investors back home.

“Even with the threat of a hard Brexit, there’s a significant amount of foreign interest in U.K. assets,” Rotchford maintained.

He argued that the latest political tensions in the U.S. are unlikely to impact foreign investment on this side of the pond for the same reason. “I don’t think the geopolitical issues would scare people away from investing in the U.S.,” Rotchford said. “I think it’s strictly the currency.”

New waves from Asia

South Korean investors haven’t been all that quiet on the American front, either.

The same Korean pension fund that bought Plumtree Court also owns a 27 percent stake in SL Green’s under-construction One Vanderbilt, for example.

In the past year, Daishin Securities acquired the 20-story office building at 400 Madison Avenue for $194.5 million and teamed up with Ken Horn’s Alchemy Properties on a $158 million purchase of an Upper West Side development site owned by the West End Collegiate Church.

Global real estate plays out of South Korea began to take off in 2015, after regulatory changes in Seoul made it easier to invest abroad. In recent years, though, currency concerns have led Korean firms to focus more on debt investments than property acquisitions in the U.S., according to industry insiders.

“They tend to be shorter-term investors, like five- to seven-year players, and sometimes less,” Marcus & Millichap’s Anton noted. “They like the steady cash flow, and in that way it’s easier for them to hedge against currency risk.”

In August, however, Korea’s Mirae Asset Financial Group was reportedly nearing a $5.5 billion deal to buy Anbang’s 15-property U.S. luxury hotel portfolio — a sign that foreign investors may once again be ready to make big bets on the States.

Another country that has become increasingly active in the U.S. more broadly, sources say, is Singapore.

Last September, Temasek Holdings’ subsidiary Ascendas-Singbridge entered U.S. markets by scooping up a 33-building office portfolio spread across Raleigh, San Diego and Portland, Oregon.

That same month, the Singapore-based real estate investment trust CapitaLand purchased a 16-property West Coast multifamily portfolio from Starwood Capital for $835 million. And this June, CapitaLand acquired Ascendas-Singbridge for $4.4 billion, creating the largest diversified real estate company in Asia.

Singapore’s REIT market is “a growing source of capital, and a somewhat newer entrant to the market,” JLL’s Cassum said.

The Singaporean investment surge, however, has so far eluded New York City, where cap rates tend to be too low to suit these investors’ preferences.

“They’re more cash-on-cash players,” Rotchford said, adding that many of Singapore’s REITs raise money from large institutions and retail investors. “And there’s an administration cost and all that, so they really need something that’s north of a 5 [percent cap rate]. It’s hard to find quality assets in New York at those rates.”

Weathering the storm

But on the global stage, overall, New York’s position as a trophy investment magnet has remained strong, and recent political and economic shifts could actually work in the city’s favor, observers say.

Many cited Hong Kong’s months-long protests as a cause for concern there, while some local developers have already scrapped major development plans and delayed luxury apartment sales as a result of the unrest.

“I think you’re going to see more Asian money coming towards the U.S.,” Shanahan said. “Hong Kong has its issues, and then South Korea and Japan are having their own little trade war over there.”

The two countries — whose top trading partners are the U.S. and China — became embroiled in a trade dispute in July rooted in World War II-era grievances and national security concerns pegged to North Korea.

South America has been another politically driven source of investment in the U.S., Shanahan added. Instability in Venezuela, the election of Brazil’s far-right government and recent political uncertainty in Argentina have all pushed more investment toward the U.S., he said.

At the same time, the Federal Reserve started to lower its benchmark interest rate this summer after upping it by a full percentage point over the course of last year.

And then, of course, there’s the lure of a city that’s still seen by many as the world’s financial capital, with plenty of new and historic towers.

“When it comes to big trophy properties, or prestige investments,” Kamins of Moody’s said, “it’s hard to rival New York.”