After years of taking a backseat to Manhattan’s nearly $2 billion hospitality market and its roughly 90,000 rooms, Brooklyn and Queens are emerging as serious competitors for the more than 56 million visitors who travel annually to New York City.

After years of taking a backseat to Manhattan’s nearly $2 billion hospitality market and its roughly 90,000 rooms, Brooklyn and Queens are emerging as serious competitors for the more than 56 million visitors who travel annually to New York City.

That’s because shadowing the Brooklyn and Queens residential market boom is an unprecedented leap in hotel development that promises to bring thousands of additional rooms to the market over the next few years.

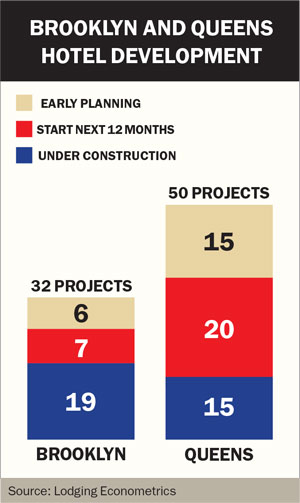

In Queens, there are no fewer than 50 hotel projects under construction or in the pipeline, while in Brooklyn there are at least 32 such projects, according to data provided by hotel industry research firm and consultancy Lodging Econometrics.

In fact, Brooklyn and Queens now account for 82 of the 204 hotel projects currently in some stage of development in the New York City market. These are historic levels of hotel development for both boroughs.

In other words, increasingly, Manhattan is no longer the only game in town.

Multiple factors are contributing to the influx of hotel rooms. In Brooklyn, residential neighborhoods like Bushwick are benefitting from a wave of retail development, which is helping to transform these once-gritty neighborhoods into tourist destinations. In Queens, a borough that has always been a modest draw for lodgers thanks to its two airports, Long Island City has emerged as an alternative budget option that comes with its own caché.

“There’s a coolness that comes into these areas,” said Geoff Bailey, a broker with SCG Retail. “People want to be there.”

Industrial makeover

Driving the outer borough hotel boom is both the decline of the city’s manufacturing sector as well as an unforeseen loophole in New York City’s zoning regulations.

Hotels have sprung up in industrial districts — categorized as M-1 — where residential development is prohibited but where hotels, which are classified as “mixed-use,” are not. “There are n’t too many commercial development sites large enough to accommodate a hotel site,” explained Dan Marks, vice president of investment sales at Brooklyn brokerage TerraCRG. “When larger M-zone sites become available, there are two ways they usually go: office and hotel development.”

Long Island City, for example, is now responsible for 22 of the 48 hotels in the borough’s pipeline, according to Lodging Econometrics. Bushwick, meanwhile, saw three separate hotel filings from three different hotel developers in the month of May alone.

Yet not everyone is a fan of the unimpeded takeover of industrial sites by hotel developers.

Last month, Mayor Bill de Blasio and City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito announced a plan that would limit hotel projects in M-1 zoned areas by requiring developers to obtain a special permit before building new hotels in the city’s Industrial Business Zones, or IBZs.

The measure came amid criticism that as-of-right hotel development in those areas has crowded manufacturers out of zones intended to protect them and also driven up land values in IBZs, thus depriving the city of valuable manufacturing and industrial jobs.

The Gowanus Inn and Yard, which is under construction at 645 Union Street, will have 82 rooms as well as a restaurant. It is set to open in 2016.

“We’re big believers in supporting our tourism sector,” said Alicia Glen, the city’s deputy mayor for housing and economic development, at the time of the announcement. “But while hotels can open in almost any commercial area, these core industrial areas have unique assets that manufacturing firms can’t find anywhere else.”

There is one important caveat to the city’s plan: The proposed requirements do not affect hotel projects already planned or in the ground. City measures requiring special permits for new hotel projects in IBZs would also not affect the area surrounding JFK; those developments would be exempt because they serve “airport-related businesses,” according to the city.

Going global

Zoning aside, real estate experts credit the transformation of the outer boroughs themselves. Up until recently, the majority of Brooklyn hotels were in or around Downtown Brooklyn.

That has changed in recent years, and new hotel projects are now popping up in more up-and-coming areas such as Williamsburg, Bushwick and Gowanus, where there’s easy access to public transportation.

In Williamsburg, the 2012 opening of Andrew Tarlow and Jed Walentas’ Wythe Hotel, at 80 Wythe Avenue, was

considered a catalyst.

Riverside Developers has been trying to finish the 183-room William Vale Hotel down the street at 55 Wythe Avenue, which is expected to open next year, and Heritage Equity Partners is working on a 150-key hotel project at 96 Wythe Avenue, which is slated to open in fall 2016.

The pace of growth in Brooklyn has been startling. For example, in the span of two weeks in May, three developers filed plans for hotel projects in Bushwick — Yoel Goldman’s All Year Management submitted plans for a 112-room development at 71 White Street, while both Riverside and Heritage said they would follow up their Williamsburg projects with a 140-key development at 27 Stewart Avenue and a 144-room project at 232 Seigel Street, respectively.

“You’re getting a lot of people who are familiar with the [Bushwick] market,” SCG’s Bailey said. “They’ve been developing multifamily in the market for years and are now moving to commercial and office and hotel.”

Gabriel Saffioti, a director at Eastern Consolidated, credits the international expansion of Brooklyn’s brand. “My experience is that more and more international tourists are traversing all over Brooklyn — every part of it — more than ever before,” he said.

Saffioti said Eastern receives calls on Brooklyn hotel sites at least once a week, with most calls coming from small funds with experience building smaller, 100-to-300-room hotels, and in some cases backed by private equity.

Saffioti said Eastern receives calls on Brooklyn hotel sites at least once a week, with most calls coming from small funds with experience building smaller, 100-to-300-room hotels, and in some cases backed by private equity.

“I wouldn’t say these are institutional quality-type developers,” he said. “They’re not building 500-room, five-star hotels. A lot of them are local, New York-based developers.”

Four miles to Bushwick’s north, across Newtown Creek, a similar pattern of hotel development is playing out in Queens, particularly in Long Island City. The neighborhood’s proximity to Manhattan — the 7 train takes riders into Midtown in 15 minutes — along with a burgeoning art and dining scene are making the waterfront neighborhood an appealing option for tourists.

Earlier this year, the popular travel guide publisher Lonely Planet shocked the real estate and travel industries when it named Queens 2015’s No. 1 travel destination in the U.S.

While Long Island City tends to grab the headlines, further west in Jamaica, developers are stepping in to capitalize on the proximity to JFK. One of them, Able Management, recently filed plans for a 27-story, 225-room Hilton Garden Inn on Sutphin Boulevard.

Flushing, meanwhile, has also captured the interest of foreign investors drawn to the neighborhood’s growing reputation as a food mecca and its two giant sporting venues. The neighborhood is home to both Citi Field, home of the New York Mets, and the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, which hosts the U.S. Open. With a large population of Asian immigrants, Flushing now rivals Chinatown in its plethora of dining options.

Chad Sinsheimer, a director at Eastern Consolidated, said given that Queens is home to two major airports, it’s “always kind of the hotel borough.” But its appeal, he argued, is distinguishably different from Brooklyn’s. As a result, the two markets are “catering to different crowds,” he said. Many hotel projects in Queens are “of the limited-service variety,” intended to serve business travelers, while Brooklyn has drawn more “boutique” full-service developments for guests happy to spend time exploring the borough.

Put more succinctly, “I think people go to Brooklyn because it’s cool. People come to Queens because it’s practical,” he said.

Flooding the market?

Real estate market observers have long speculated about whether the city’s hotel market is venturing into oversupply.

Through the first nine months of the year, there were 198 hotel projects with 32,000 new rooms slated to hit the New York City market over the next several years, according to STR, the leading research company on the hotel industry. That pipeline has grown by nearly 19 percent from the first six months of 2014.

At the same time, average room rates also slipped this year on a citywide basis. While room rates were up 5 percent nationwide in the first half of the year — climbing 5.2 percent in the 25 largest lodging markets excluding Las Vegas — they dropped 1.9 percent in New York City during the same period, STR said.

At the same time, average room rates also slipped this year on a citywide basis. While room rates were up 5 percent nationwide in the first half of the year — climbing 5.2 percent in the 25 largest lodging markets excluding Las Vegas — they dropped 1.9 percent in New York City during the same period, STR said.

The decline was felt most prominently in Manhattan but did touch Brooklyn as well — even after a slight rebound during the peak summer months, room rates were still down 0.4 percent through September compared to the same period last year. Queens, however, was relatively insulated, with room rates up 2.9 percent, according to STR data.

Despite falling room rates, demand has been steadily climbing.

Jan Freitag, senior vice president of lodging insight at STR, said room demand in New York City has “grown at a healthy clip” over the past few years and that the trend has persisted. After a relatively tepid start to the year, room demand — the number of hotel rooms sold, as defined by STR — was up 6.2 percent in Brooklyn for the year through September and 9.2 percent in Queens.

Occupancy rates have also been relatively strong, hitting 89.2 percent in Brooklyn at the end of September — up 4 percent year-over-year. In Queens, occupancy rates surged to 91.7 percent at the end of September, up a notable 8.9 percent from the year before.

“For all intents and purposes, that meant hotels were sold out,” Freitag said.

He added: “The high level of occupancy is indicative of a healthy market, which is why you get new developments.” So why the lackluster growth in room rates?

One reason could be Airbnb, the controversial home-sharing service, which has roughly 27,000 listings in New York.

“Airbnb is something we hear a lot about from hotel owners,” Eastern Consolidated’s Saffioti said. “It has enormous traction throughout the city. At the end of the day, individuals benefit so much from the fact that you can stay in a home with a kitchen.”

In response to a request for an interview, Airbnb released a statement saying that nearly a third of New York City visitors who used its service last year chose Brooklyn as their destination. That number is “up from the year before, and we see no sign of that slowing down,” the company said.

Amid increased concern over market fundamentals, some developers in New York City have already balked on projects or found it difficult to raise capital to finance hotel developments.

According to Eastern Consolidated’s Sinsheimer, one hotel development deal in Chelsea fell apart because the developer’s equity partners didn’t want to provide any financing. “They didn’t want to take any more hotel projects,” he said.

Nevertheless, there are those who remain bullish on the market. “I would never bet against New York,” Freitag said. “It’s one of the rare cities where it could be said that if you build it, they will come.”

SCG’s Bailey described the anxiety as being par for the course. “Whenever there’s a boom or a perceived bubble for development, there’s always that fear,” he said. “People had it about the residential market as well, and even through the downturn rental rates in Brooklyn stayed the same.They didn’t go down, they held.”

“It may take longer for that [new hotel] inventory to be absorbed,” Bailey added, “but it will be absorbed.”