Newmark’s “friends and family” offering seemed like manna from heaven. At $18 or $19 a share, it was a sizable discount from the original high of $22 that the firm’s executives boldly predicted the stock would trade at once it hit the opening bell.

While all of those figures were eventually lowered, a number of brokers and executives at the company opted in, buoyed by CEO Barry Gosin’s infectious enthusiasm.

“Barry owns a bunch of stock and he was very much like, ‘We’re all in this together,’” said one person involved in the initial public offering. “A lot of big brokers put a lot of money into that.”

But much of that money vanished on Day 1.

When Newmark debuted on the NASDAQ — one year ago, in December 2017 — its stock clocked in at just $14 a share, wiping out about a quarter of the value of the “friends and family” investments.

Things have only gotten worse for Newmark’s shareholders since.

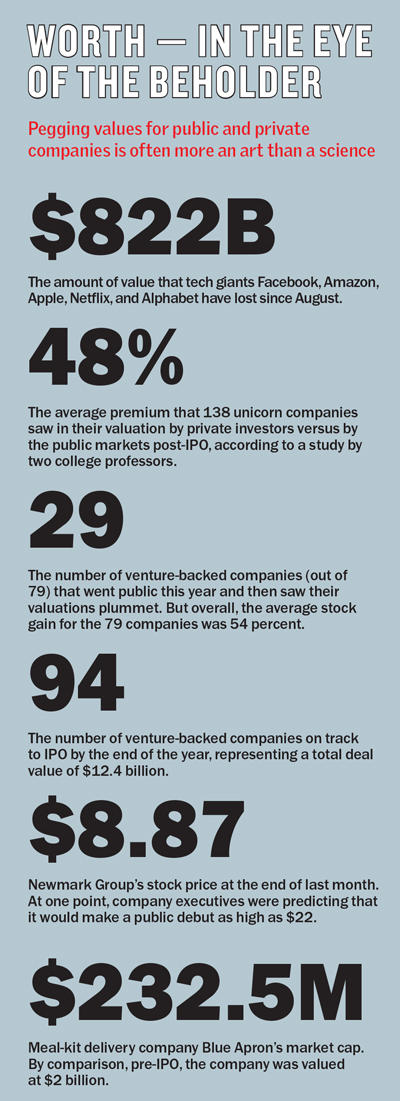

The low point came in late October, when S&P Global Ratings downgraded Newmark Group to junk-bond status. Last month, the company’s stock stood at just under $9.

Analysts trace Newmark’s IPO flop to a number of factors — bad timing, accounting irregularities and confusion over earnings, to name a few. But there was also a bigger issue at play.

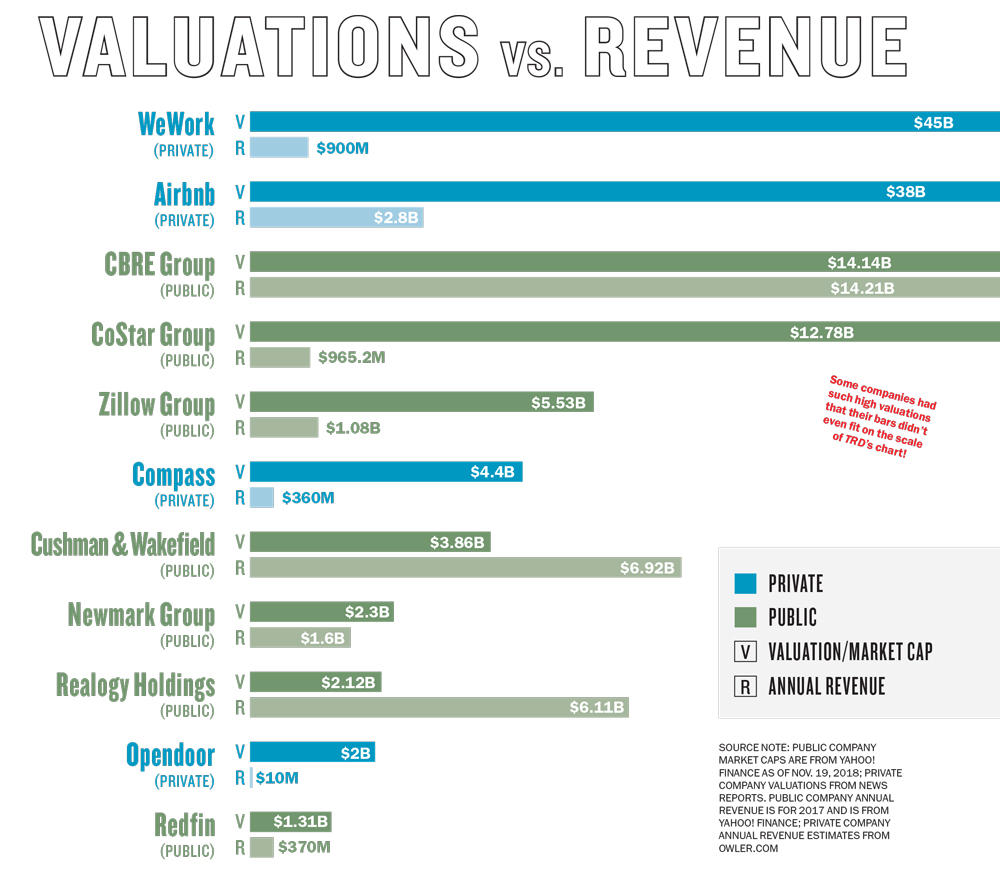

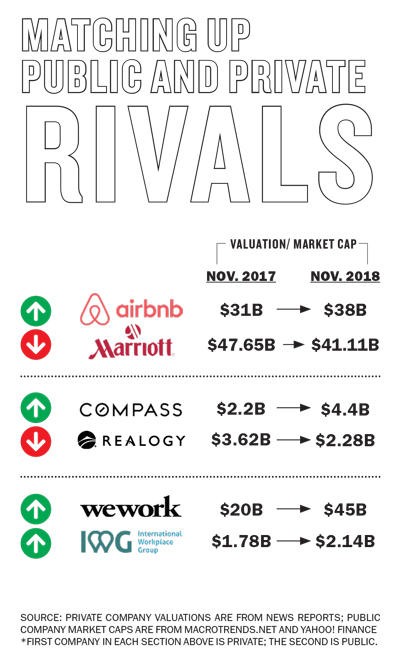

As mega-investments from venture capital funds inflate the valuations of private startups to never-before-seen levels, the disparity between public and private companies is on the rise. Sources say that the delta is wider than it’s ever been — creating problems for public companies that are now scrambling to keep up and for investors who’ve weathered billions of dollars in losses.

Meanwhile, eye-popping valuations assigned to companies like WeWork, Compass and Airbnb — along with the mixed reception some IPOs have received on Wall Street this year — have made private companies think twice about going public. In real estate circles, that’s stoked fears of a bubble, with some predicting that these venture-backed firms will be unable to sustain their growth.

“It’s unusual for there to be so much price speculation based on an IPO that’s out in the distance,” said Rett Wallace of Triton Research, which analyzes pre-IPO companies.

He said there’s a “scarcity value” to some of these firms — meaning they are seen as commanding names in the market. But when they go public, the stories they’ve sold to investors are tested. “Sometimes the narrative is true, and sometimes the narrative is less true,” he said.

Already, the harsh reality has hit several newly public tech firms like Blue Apron, which was once valued at $2 billion and is now worth $232.5 million. And Snap, the parent company to messaging app Snapchat, was valued at $16 billion in 2015, but is now worth $8.4 billion.

Last month, Snap confirmed that it is facing scrutiny from regulators over its 2017 IPO — specifically, whether it sufficiently disclosed the competition it faces from Instagram. The allegations were first raised in a class-action lawsuit filed in May 2017.

Beyond Snap, investors are looking at tech stocks more critically, resulting in a major sell-off. Since the end of August, tech giants Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Alphabet (Google’s parent company) have lost a combined $822 billion in value, as the New York Times reported late last month.

There are also those who believe that regulators should be looking at why private company valuations bear little resemblance to reality.

For example, WeWork, which has 10 million square feet of office space leased, raised another $3 billion last month at a stunning $45 billion valuation. That valuation is far higher than major landlords like Blackstone Group, which has 230 million square feet of office space and is worth $38 billion.

“[Blackstone] owns millions of square feet that are tangible assets, yet WeWork has a higher valuation,” said Michael Beckerman of research firm CREtech.

While the co-working company may be growing at an insane clip, it is also losing $1 billion a year — perpetuating the need for more capital. All of that has raised questions about its long-term prospects and the fate of other VC-backed firms.

“I don’t know when the reckoning comes,” Beckerman said.

Mind the gap

The simple explanation of why private companies appear so much more valuable on paper is that publicly traded stocks are based on real-time performance, while VC-backed firms are valued based on their potential for growth.

In other words, if investors think a company has promise, they’re willing to pour in capital and hope for a big payday down the road.

Triton’s Wallace said those VC-backed companies are buoyed by a “belief system for what they can become.”

However, that belief is often little more than a fantasy, according to business professors Ilya Strebulaev from Stanford University and Will Gornall from the University of British Columbia.

Last year, the duo co-authored a study of VC-backed unicorns that found a serious gap between “post-money” valuations, or the numbers that are often reported in the press, and the companies’ fair value.

The study — which looked at 135 companies, including Compass and WeWork — discovered that on average, post-money valuations were 48 percent higher than fair values, which they determined by analyzing the companies’ financial terms and legal filings.

“That’s a pretty large gap by any standard of imagination,” said Strebulaev.

The disparity has been front and center this year as real estate stocks have taken a hit.

IWG, the WeWork competitor formerly known as Regus, saw its stock plummet 20 percent to $238 per share in August after the company ended takeover talks with suitors. Still its current market cap of $2.1 billion is up slightly from $1.78 billion last year.

While IWG’s path forward is uncertain — it lost its finance chief in September — other public companies are pulling out the stops to compete with well-funded, private rivals.

The rise of iBuyer programs — in which companies buy and sell homes directly from consumers — embodies that phenomenon fully.

Over the last 18 months, Zillow Group, Redfin and Realogy Holdings have all jumped into the sector to better compete with market leader Opendoor, which was founded in 2014 and has raised $1 billion to date at a $2 billion valuation.

At Realogy, the residential brokerage giant with $6.1 billion in 2017 revenue, executives are fighting to turn things around after losing a staggering $2 billion in value over the last 12 months. The firm had a market cap of $2.12 billion as of mid-November.

By comparison, Compass is projecting $1 billion in revenue this year, but is valued at $4.4 billion after a $400 million injection from SoftBank and the Qatar Investment Authority in September.

With $1.2 billion of investor capital in its coffers, Compass has been scooping up regional firms and grabbing market share. All the while, Realogy’s stock has been in a downward spiral. As of last month, it was down 40 percent year over year.

“I know shareholders expect better results,” Realogy CEO Ryan Schneider said on an August earnings call.

This fall, analyst John Campbell of Stephens Inc. characterized Realogy’s situation as a “perfect storm,” fueled by competition for top agents, rising commission payouts and a housing slowdown. “People view it as the dinosaur,” he said.

Although the lopsided playing field for public and private companies has infuriated Compass’ rivals — who say the company’s burn rate isn’t sustainable and question its profitability — investors write big checks precisely so that startups can grow fast and annihilate the competition.

Kenneth Chenault, former American Express CEO, told Forbes in October that growth rate for VC firms is a matter of survival.

“The reality is that you’re not going to be around long-term unless you’re able to grow and generate attractive economics,” said Chenault, who sits on the board of Airbnb and was an early investor in Compass.

But public companies are held to a different — and far more punishing — standard.

Zillow is another case in point.

The Seattle-based listings giant was rebuked by the markets in a big way last month, losing $2 billion in value overnight, bringing its market cap down to $6.5 billion, after a disappointing earnings report. On Nov. 6, after reporting that more agents had stopped advertising on its Premier Agent program than expected, the company watched its stock sink by roughly 20 percent to $29.99 per share.

CEO Spencer Rascoff fired off 14 tweets, acknowledging that “change is always hard” but reassuring investors and agents that Zillow had already made adjustments to the program. “Premier Agent issues are very solvable,” he told analysts.

But those attempts to reassure the Street didn’t stop a massive sell-off by investors.

On Nov. 7, Zillow’s investors went bonkers. Trading volume hit 21.8 million shares, compared to a daily average of 2.4 million. Rascoff — generally a prolific tweeter — was radio-silent the entire day.

Though analysts predict the road back will be long, its stakeholders are doubling down.

Richard Barton, the company’s co-founder and executive chairman, bought $19.2 million worth of Zillow stock late last month; Jay Hoag, a venture capitalist who sits on Zillow’s board, shelled out $25 million to up his stake in the company, regulatory filings show.

In some cases, investors and stakeholders have taken their disputes over valuations to court (see related sidebar).

In November, Forest City Realty’s former CEO Albert Ratner attempted to slam the brakes on Brookfield Asset Management’s bid to buy the REIT, arguing in a federal lawsuit that the $6.8 billion purchase price was a “shameful value giveaway.” But a judge declined to halt a vote by shareholders, who on Nov. 15 approved the deal.

As a segment, REITs are their own beast. But they, too, have been grappling with falling stock prices stemming from low cap rates and fears of rising interest rates.

While SL Green Realty’s stock price hit a five-year high of $134 in March 2015, it’s lost about 30 percent of its value since then. Last year, the REIT kicked of an aggressive $2 billion share buyback program to return some value to shareholders.

To raise money for that buyback, SL Green is selling off a handful of assets including a 48.9 percent stake in 3 Columbus Circle and an office condo at 1745 Broadway for $633 million.

“Our discounted stock price continues to be the best investment opportunity we see in the city,” the REIT’s president, Andrew Mathias, told The Real Deal last month.

Preserving privacy

Given how vulnerable public companies can be to the whims of the market, mega-fundraising rounds are giving VC-backed companies an option that didn’t exist in the past: staying private for a lot longer.

But investors seem to be on board with that delay, even though IPOs generally mean they can cash out.

“You can sell stories in the private market much longer without having to face the accountability of a liquid public market,” said Triton’s Wallace. “Without SoftBank, you might see WeWork going public in the next year. But not everyone wants to be public.”

Take Airbnb, which is reportedly worth $38 billion.

According to Bloomberg, an internal dispute over when to go public resulted in CFO Laurence Tosi’s resignation in February. CEO Brian Chesky reportedly told the finance chief that Airbnb would not go public this year.

The company’s founders and early employees have already cashed in $350 million in equity and have little incentive to go public, Bloomberg reported. That’s even though Airbnb was profitable last year with $93 million in earnings on $2.8 billion in total revenue.

“I’ve met a lot of CEOs that say, ‘I’m very long-term-oriented,’” Chesky told Forbes in October. “But the only metrics they review at a board meeting [for public companies] are the metrics about the sales of the product, essentially.”

Over the summer, SoftBank’s Justin Wilson said the Japanese conglomerate gives the companies it invests in leeway in deciding when to go public.

“What we actually think we bring is long-term, patient capital,” he said. “It’s not that we’re going to invest and hold forever … but we’re aligned in our vision and mission to support entrepreneurs in backing what they think is right.”

While IPOs are a payday for investors and other stakeholders, there are benefits to remaining private.

“The positive for staying private would be the ability to raise capital at a valuation you somewhat pick and use the competition in the private funding arena to determine that private valuation,” said Jeffrey Berman, a general partner at real estate venture capital firm Camber Creek. “When you have that amount of money, you can buy your way out of trouble.”

The downside has been a nonissue for some companies backed by SoftBank, which is famously headed by Masayoshi Son. The company has been known to buy out stakes of some early investors, several sources said.

Despite all of the hemming and hawing about when to go public, the number of IPOs is soaring.

According to research firm PitchBook, there are 94 VC-backed companies on track to IPO by the end of the year, representing a total deal value of $12.4 billion. That’s more than any year since 2012, when Facebook went public.

And unlike a decade ago, investors are backing companies with steep losses, banking on the fact that it costs money to grow quickly.

In 2017, 76 percent of companies that went public were not profitable, according to research by professors at the University of Florida.

But the end game is still “IPO or bust,” said one investor. “No other options exist.”

High bar for IPO

Recent IPOs have been a litmus test for private valuations.

Of 79 VC-backed companies that went public this year, 28 saw their valuations plummet, according to an analysis by TRD. But overall, the average stock gain for the companies was 54 percent.

When discount brokerage Redfin went public in July 2017, CEO Glenn Kelman said the market volatility was the enemy he most feared.

“We didn’t want the stock to go down, but we didn’t want it to go up too much either,” he wrote in a LinkedIn post four months after the firm’s IPO.

“When the stock price doubles on the first day of trading, it makes for a nice headline, but leaves you with shareholders set up for disappointment,” he said.

Beyond the first day, the pressure on public companies to generate profits is very real. Many argue that it’s way too real.

In 2012, former Goldman Sachs partner Greg Smith penned an explosive op-ed explaining his decision to resign from the investment bank, which went public in 1999. His piece detailed the bank’s “toxic” and “destructive” culture, which was hyperfocused on quarterly profits. “To put the problem in the simplest terms,” he wrote, “the interests of the client continue to be sidelined in the way the firm operates and thinks about making money.”

And real estate companies across the board are facing those quarterly pressures today.

Even just the whiff of competition may be taking a toll on CoStar — the powerful data provider, which is worth $15 billion. Since August — when rival Moody’s announced plans to buy Reis Inc. for $278 million — CoStar has seen a sharp drop in its stock. But analysts aren’t convinced that’s the sole reason for CoStar’s dip, which they attributed to the market slowdown. “You can compete with part of CoStar, but not the whole lot,” one said.

As of mid-November, the firm’s stock price was just over $351, down 20 percent from $442 in August.

No doubt private companies are watching these market fluctuations closely to time their own IPOs.

“The ‘X factor’ is the market, the IPO window,” Wallace said. “Some companies want to go public and can’t because the IPO window isn’t there for them.”

Even when the timing is right, going public isn’t as simple as flicking a switch.

As Cushman & Wakefield prepped for its IPO this past August, the commercial brokerage enacted a painful round of cost-cutting, which sapped broker morale and prompted high-profile brokers to jump ship. Top producers including Paul Massey, Bob Knakal, Peter Hennessy, Gene Spiegelman and Gus Field all left before the IPO.

But the belt-tightening paid off with a successful stock market debut. Shares closed at $18.55 on the first day of trading, and after some bumps this fall, the stock was trading around $17.75 per share in mid-November.

In the case of Redfin, Kelman documented in unflinching detail the mixed signals he received during his harrowing two-week roadshow meant to drum up investor support ahead of the IPO.

On a flight from Chicago to Seattle, he called Redfin Chairman Robert Mylod to warn him that the IPO was going to be a “fiasco.” After each investor pitch, underwriters from Goldman Sachs — who were facilitating the IPO — had been tracking stock orders. On a line chart, the lackluster orders “looked like a dying slug.”

Ultimately, the orders poured in, and Redfin’s stock skyrocketed 45 percent to $21.70 on Day 1.

But as of the middle of last month, the stock was at around $15 per share. And on a third-quarter earnings call, after reporting that Redfin’s net income tumbled 67 percent to $3.5 million, Kelman said: “We’re not ending the year market-wide with a bang but with a whimper.”

Too big to fail?

It was sheer coincidence that WeWork announced its latest funding on Nov. 13, the same day New York Times columnist Andrew Ross Sorkin — the author of “Too Big to Fail” — penned a piece arguing that landlords can’t afford to let WeWork go bust.

“If they were to let WeWork fail,” he wrote, “those landlords would risk depressing commercial real estate prices to such a degree that it would create a serious sense of pain for the country’s largest real estate owners.”

While not everyone agrees, WeWork is clearly setting the market in cities like New York, where the company recently became Manhattan’s largest office tenant, with a total of 5.3 million square feet — and counting.

“WeWork is an enormous consumer of space … and that’s generally helped keep things tight in the market,” SL Green’s Mathias said during an October earnings call, two days after WeWork inked a deal with the REIT to lease out all of 609 Fifth Avenue.

Whether inflated valuations constitute a bubble, though, has been a matter of fierce debate.

Camber Creek’s Berman said there’s no question the overall market is frothy. “Low interest rates have fueled massive amounts of capital available to be deployed,” he said, noting that not all investors are making disciplined bets. “If there’s a great company, there’s competition to get in the round. Opportunities for founders to take in gobs of capital from these ravenous venture firms are real.”

Last fall, Hans Nordby, CoStar’s managing director of portfolio strategy, said the current climate feels similar to the run-up to the 1999 dot-com bust.

“WeWork’s valuation is out of whack,” he was quoted as saying by National Real Estate Investor. “Some tech companies like Apple and Google have real profits … WeWork isn’t a bad idea, but we’ve done the math and we’re confused.”

But others — including CREtech’s Beckerman — argued that today’s valuations aren’t as speculative as they were back then. “It’s not dot-com 2.0,” he said. “There are customers, there are people using these platforms.”

Likewise, Berman argued that the ecosystem of real estate tech firms is still young. “Certain companies are attracting valuations that seem quite high,” he said. “At the same time, we’re at the beginning of just realizing the value they can create in the largest asset class in the world.”

‘Stuff of fairy tales’

All of this hasn’t stopped economists and attorneys from warning that inflated valuations put investor capital at risk.

The concern is more acute when funds use workers’ retirement savings and pensions, according to attorney Darren Robbins, a corporate securities lawyer and partner at Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd in California.

In an April essay, published on a Law.com-affiliated website, he cited Union Square Ventures — a backer of location-search app FourSquare, crowdfunding platform Kickstarter and Flip, which helps renters sublet and find flexible leases.

Union Square’s roster of investors includes pension funds in California, Oregon and Wyoming. “Sometimes, unicorns really are the stuff of fairy tales,” Robbins wrote. “When the truth about such companies is revealed, the value of those investments often evaporates.”

Even when investors aren’t deploying people’s life savings, those who invest later — and pay more per share — can get burned if the company goes public and the stock tanks.

“If I’m an early investor in Compass or WeWork — if I invested at the $10 million, $20 million or even $100 million valuation — I’m still going to do great,” said Camber Creek’s Berman. (Compass’ Series A shares were priced at $10 per share while its Series F shares were priced at $118.57 per share, according to PitchBook and company documents.)

But not all investors enter the fray early on.

And even assuming founders aren’t intentionally spinning a yarn, 30-something entrepreneurs haven’t lived through a recession or drop in valuation.

Strebulaev, of Stanford, said it’s dangerous for investors to conflate private and public valuations because it can give them a false sense of wealth.

“It’s a matter for regulators,” he argued. “There are more and more investors who are not professional venture capitalists; they’re less sophisticated, specifically in the private market.”

For a time, regulators seemed to be headed in that direction.

During a 2016 speech, the former chairwoman of the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission Mary Jo White cautioned that “being a private company comes with serious obligations to investors and markets.”

White, who was nominated to the position by President Barack Obama, took particular aim at tech unicorns, whose “eye-popping valuations” are highly subjective and had raised concerns among regulators, she said. “The concern is whether the prestige associated with reaching a sky-high valuation fast drives companies to appear more valuable than they actually are,” she said.

She also noted that the IPO process is not just about raising cash, and that it’s also about shedding light on its operations and ensuring investors are protected.

Under Chairman Jay Clayton, who was nominated by President Donald Trump, the SEC is looking to ease disclosure rules and regulations surrounding capital raises — a move that’s elicited mixed reactions.

“You need both,” said a former SEC enforcement official. “You need good disclosure rules that are easy for entrepreneurs to follow that want to raise capital, and you need those same people to be honest about the future prospects of their enterprise.”

The potential for investors to lose money increases when they’re in the dark.

“This is the criminality of Wall Street,” said one investor. “The folks that are underwriting the deal, who have no capital in the deal, they don’t care what happens to the stock.”

This fall, Compass said more than 1,100 agents participated in an Agent Equity Program, which lets them use commission payments to buy company stock options.

While that might sound enticing, one New York brokerage executive called the offering “golden handcuffs” that ensure Compass can retain agents and meet its self-imposed growth hurdles.

And Stephen Shapiro, co-founder of Beverly Hills-based Westside Estate Agency, called the offering a “risk that I don’t think most agents are going to understand.”

In the case of Newmark, the “friends and family” who purchased options lost their shirts when the stock sank early on and never recovered.

“The people who lose are the small fish, the employees and brokers,” said one industry veteran, adding that Newark’s agents probably signed multiyear contracts to stay with the company.

“Now,” the source said, “they’re not even in the money and they’re stuck with the lock-in.”

— Rich Bockmann contributed reporting to this article. Kevin Sun compiled the data on both charts.