Anyone who has banked online, shopped on Amazon or shared digital photos recently can understand why real estate firms are clamoring for new technology.

Anyone who has banked online, shopped on Amazon or shared digital photos recently can understand why real estate firms are clamoring for new technology.

It’s been a decade since the listings portal StreetEasy debuted, making data accessible to New Yorkers. But there have been few game-changing startups in its wake.

To fill the void, a burst of activity on the real estate tech front over the past two years has challenged the sector’s reputation as slow moving and resistant to change.

Call it real estate’s tech arms race.

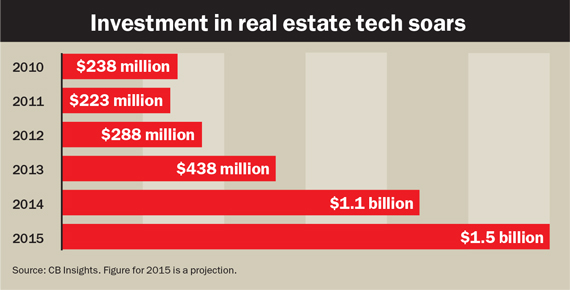

Overall, investors threw a projected $1.5 billion at real estate tech startups in 2015, according to venture capital database CB Insights. That’s a jump from the $1.1 billion in venture funding in 2014 and represents a more than 350 percent increase from 2010.

New York is home to several of 2015’s top tech fundraisers, such as residential brokerage Compass, which has raised $123 million to date, and VTS, a cloud-based tool for the commercial leasing sector that’s raised $32 million.

Of course, tech entrepreneurs have been starting to circle real estate (and making headlines) for several years, seizing on an industry that’s lagged behind other sectors like finance and publishing.

“It’s a huge market with lots of pain points, and there really hasn’t been a lot of technology applied to the industry,” said Caren Maio, founder and CEO of listings database Nestio, which raised $8 million last month in a funding round led by Trinity Ventures, bringing the company’s total investment to $11.9 million.

While the early wave of real estate tech — including companies like StreetEasy, which was acquired by Seattle-based Zillow — put data in the hands of consumers, today’s startups are, more often than not, looking to arm real estate professionals and companies with tools to broker deals faster and compete with rivals.

“There’s just been an explosion, frankly, of the number of startups aimed at the real estate industry,” said Noel Fenton, co-founder of Trinity, a pioneer in funding the real estate sector. The firm has invested in LoopNet, a commercial real estate listings service, and DotLoop, which provides an online system for handling paperwork associated with real estate transactions, as well as others.

Noel Fenton

Fenton described a sort of marketplace tipping point, saying residential and commercial firms alike are rushing to use new technologies to ensure they are “not to be left behind.”

In addition, many real estate firms, particularly on the commercial side, are under pressure from their institutional backers who are used to tracking their dollars in real time through the financial markets. Startups have now seized on that as an opportunity to create technologies that enable these firms to better quantify their performance for themselves and investors.

“When you have this much industry money being poured into the market, these guys demand information,” said Nick Romito, co-founder and CEO of VTS.

Fenton said even though many startups are bound to fail, there’s no going back for the industry. “There are 175 startups trying to change the real estate industry,” he said. “Most of them will fail, but the movement will not fail. People that don’t embrace it will be left behind.”

Follow the leader

While commercial brokerages have embraced real estate tech, residential firms are playing catch-up.

The gap may explain investors’ outsized interest in Compass, a tech-enabled brokerage founded in 2013 by Robert Reffkin and Ori Allon, which has an $800 million valuation.

Clelia Peters — Warburg Realty’s director of strategy and innovation and the daughter of firm head Frederick Peters — said Compass’ valuation has made her firm rethink its tech strategy. “Certainly, it’s motivated a lot of discussion and thought for us,” she said.

Reffkin put it this way: “This is an industry where companies aren’t investing in technology, so what people had two years ago — in the vast majority of cases — is what they have today. Things have not changed much, which creates great opportunity.”

It’s no secret that Compass has struggled to explain its technology to skeptics. But Reffkin described a suite of tools aimed at making agents more efficient. It recently rolled out a real-time market report. Other tools automate tasks like valuing properties, designing marketing materials quickly from online templates and creating itineraries for residential showings in the most logical sequence.

“Time is money to an agent,” he said.

Of course, the firm, which has indisputably disrupted the residential world by poaching top talent from rivals with its tech approach and promises of equity stakes, was not the first to combine tech and brokerage. But the others operating today have struggled to garner anywhere near as much funding and attention.

Tech-powered brokerage RealDirect, which launched in 2009, gives sellers access to data so that they can track their property in terms of time on the market and pricing, in order to make prudent decisions. The company has raised $2.7 million to date.

RealDirect’s technology can also draw custom floorplans for clients and has a proprietary tool for brokers that generates leads for new deals.

Doug Perlson

“Most brokers think that the technology you’re going to utilize is going to make your listing sell better, faster,” said founder and CEO Doug Perlson. “The truth is, most real estate brokers care about, ‘How do I get more listings? How will I generate more leads?’”

Other tech-powered brokerages are TripleMint (formerly Suitey), a residential brokerage launched in 2011 that raised $1.7 million and offers online property search tools, and LG Fairmont, a five-year-old firm that’s building a data set on buyer behavior. (Metrics include things like how many times a broker showed a unit as well as more indirect data like subway ridership in the area.)

“Data, for the most part, is driven by the supply side — what is for sale, attributes around properties,” said co-founder Derek Lee, who has a background as a quantitative trader. The firm, which raised $1 million, has 130 agents and said it sold $150 million worth of real estate in 2015.

On the commercial side, there’s also TheSquareFoot, which launched in 2010 and has raised $2.5 million.

Industry observers, however, said it’s been Compass’ phenomenal fundraising and out-of-the-gate success that’s been the real wake-up call for the industry.

“I think that pushed other firms to say, ‘Man, how do we replicate that?’” said Nestio’s Maio.

At a lunch meeting late last year, Bill Raveis — head of the suburban residential brokerage William Raveis — told his brokers that they shouldn’t think of the firm, which he founded in 1974, as a real estate company. Instead, they should consider it a marketing and technology firm that happens to be in real estate. The company recently spent $1 million to establish a 25-person team to focus on digital marketing and technology. And it plans to spend $1.5 million on digital marketing and technology in 2016.

What has that money gotten Raveis so far? An automated valuation model, an open-house app and new 3D capability to show properties. The firm, which operates a mortgage arm, has also created a paperless mortgage process.

Build or buy?

As brokerages seek to expand their tech offerings, a key question is whether to build or buy a technology platform.

There are clear advantages to both: By developing technology in-house, companies control and customize all aspects of the product — though it could take years to develop. Partnering with a tech startup can lead to immediate results, but companies may end up with only 80 percent of the features they want. It can also be more expensive in the long run.

“If you’re not innovating on the technology for lead generation, you will pay a lot of money to third parties,” said RealDirect’s Perlson.

On the other hand, Ryan Masiello, co-founder of VTS, said one of the company’s early challenges was convincing real estate companies to eschew their own platforms.

“People were leaning on the fact that they had an internal system they’d built,” he recalled. To woo clients, the startup demonstrated how it could customize its leasing platform to fit different needs.

Today, VTS’s client roster includes SL Green Realty, Vornado Realty Trust, JLL and CBRE, which all use it to track rent rolls and analyze performance. For example, from a mobile device these mega firms have real-time access to their leasing portfolio and can easily spot which properties have vacancies and leasing coming due — or analyze market trends.

Last January, VTS scored a major coup when private equity giant Blackstone Group, which has nearly 100 million square feet of office space globally, had a “build or buy” moment, said Romito. It opted to buy a $3.5 million stake in the startup.

Last January, VTS scored a major coup when private equity giant Blackstone Group, which has nearly 100 million square feet of office space globally, had a “build or buy” moment, said Romito. It opted to buy a $3.5 million stake in the startup.

These days, most (if not all) residential brokerages have consumer-facing websites and apps. But few firms offer the means to build on the information they provide.

That hole, however, is starting to get filled.

Douglas Elliman has spent the past 12 months making a “big push” on technology, said Stephen Kotler, the firm’s chief revenue officer.

Five years ago, it launched a customer relationship management (CRM) platform called Elliman Edge, with robust tools such as “Find Buyers,” which uses reverse analytics to show sellers and brokers which buyers are looking at their properties. (Potential buyers are identified based on their registration on Elliman’s website, where they plug in their preferences.)

“The old approach to real estate was a shotgun approach. You’d market to everyone,” said Kotler. “Instead of having an email blast sent to 1,000 people, we’re laser-targeting the buyers who want to buy this kind of property.”

The Edge also has a “Seller’s Report,” an automated analysis for sellers showing activity in their segment of the market over the last seven days.

Kotler said the firm has invested “substantially” in upgrading the Edge since introducing it. And last year it hired Chief Technology Officer Jeff Hummel, a former technology executive at ING Direct and Capital One, who will launch a set of new tech tools during the first quarter.

Meanwhile, in 2015, Town Residential introduced a cloud-based platform, developed in-house and accessible anywhere, which gives agents access to listings, email and the firm’s transaction system.

And the brokerage is now evaluating ways to adapt its offerings for potential buyers and renters. “It’s no secret that millennials do most of their shopping online,” said Jared Cohen, Town’s marketing manager. “When it comes to real estate, [we’re asking ourselves], ‘What can we give them from an information and content perspective prior to them reaching out to one of our agents?’”

To address that question, Town looks at how consumers search its website and then “merchandises” listings that fit their interests. “If someone has been looking at penthouses, we [show them] penthouses on our site,” Cohen said.

Appetite for partners

Even as brokerages bolster in-house tech, other firms are seeking partnerships to get a leg up.

Historically, real estate companies felt threatened by new technology — particularly if it reduced the role of agents. “There’s some apprehension in the brokerage community about some of these startups coming directly after them,” said Fenton. “They say relationships are more important than technology, and they dismiss this stuff. … But as it turns out, you can’t just dismiss it, because when change is happening, change is happening.”

Warburg’s Peters, who is also a co-founder of MetaProp, a New York City-based real estate technology “accelerator” that mentors startups, echoed the sentiment.

“There really is a lack of sophisticated tools to allow brokers to do their business more effectively — tools that assume the broker will still exist,” she said. “That’s where we definitely see an opportunity, in terms of working to develop those tools.”

To that end, Warburg has a two-pronged approach to rolling out tech to its agents. The firm is both developing broker tools to make it easier to complete transactions and keeping a close watch on third-party tech offerings.

To that end, Warburg has a two-pronged approach to rolling out tech to its agents. The firm is both developing broker tools to make it easier to complete transactions and keeping a close watch on third-party tech offerings.

Via MetaProp, Peters has a birds-eye-view of nascent technologies that could upend the industry. Peters (personally) and Warburg have both invested in MetaProp’s cohort of startups. “It hasn’t happened yet, but theoretically MetaProp gives us early exposure to companies in the industry that might be important to us as customers or strategic investors,” she said.

Others firms are also starting to partner with tech startups.

In October, CBRE inked an agreement with VTS to utilize the startup’s leasing management and client reporting system. Elliman is working with Nestio to access open listings data for rentals, and Maio said she’s getting calls from teams within large firms.

Meanwhile, Zillow is hosting hackathons — in which hundreds of coders gather to come up with computer programs that apply public data to real estate uses. By hosting these sessions, Zillow can get an early read on potential startup ideas and consider whether to monetize the technology itself.

Brokerages are also demonstrating an appetite for acquiring technology elsewhere.

In 2014, Realogy Holdings — which owns Corcoran Group, Citi Habitats and Sotheby’s International Realty, among other brokerages — paid $166 million for ZipRealty, a California-based brokerage that uses an Internet marketing platform.

There’s also been recent activity on the commercial side. In November, CBRE bought Forum Analytics, a Chicago-based company that uses data to forecast where to build or lease retail locations. And just last month, JLL said it was buying Corrigo Inc., a cloud-based facility management provider. “Two years ago,” said Zach Aarons, another co-founder of MetaProp, “you wouldn’t start a real estate company and think, ‘My exit will be JLL.’”