In the bedroom that Andrew Kim shares with his girlfriend, Michelle, and their pug, Emilio, there is a 60-inch TV mounted on the wall, a vanity for Michelle and an automatic feeder for the pup. “It’s a tight space,” said Kim.

The couple, both in their late 20s and employed in creative industries, recently moved from a one-bedroom apartment into a three-bedroom in Ridgewood, Queens. But rather than move so they could have more space, they took on two roommates.

“We decided to move because we wanted to pay less in rent,” Kim said. “So we asked two of our friends to move in with us.”

Kim’s situation is similar to that of many New Yorkers across the board. While roommates are often thought of as a reality that recent college graduates and early 20-somethings have to endure, there is an increasing number of New Yorkers sharing apartments with friends, lovers and sometimes strangers, deep into their adult lives.

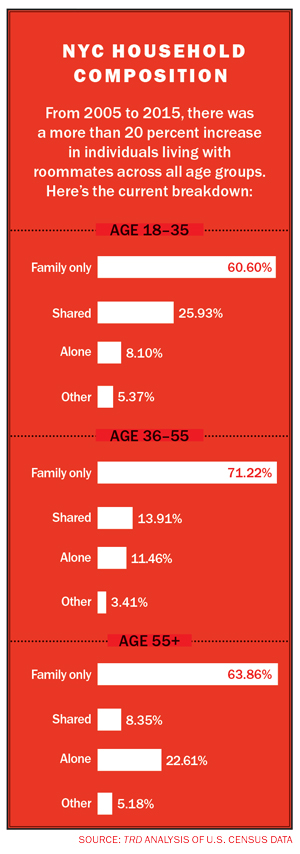

From 2005 to 2015, the percentage of individuals with roommates in New York increased among milliennials, Gen Xers and baby boomers by more than 20 percent across each age group, according to an analysis of U.S. Census data by The Real Deal.

Related: Is co-living’s awkward phase permanent?

In 2015, 26 percent of millennials, who range from 18 to 35, were living with roommates or an unmarried partner, compared to 20 percent in 2005. Among 36- to 55-year-olds, 14 percent were living with roommates, up from 11.3 percent. Those situations include two roommates living together, a family renting out an extra room and other nontraditional living arrangements.

Experts TRD spoke to said more people are sharing space for budgetary reasons, especially as the rise in rent continues to outpace the rise in income. Indeed, median gross rent increased 18.3 percent between 2005 and 2015, while median household income for renters increased just 6.6 percent, according to data from NYU Furman Center.

“Income growth has not kept pace with the growth in for-sale and rental prices,” said Felipe Chacon, a housing economist at the real estate firm Trulia. Both millennials and the midprofession generation “are seeing record rates of living at home, or with roommates.”

The average New Yorker would have to spend 34.3 percent of their income to pay for a one-bedroom apartment. (It’s just a little less for millennials.) That’s above the 30 percent benchmark, which according to federal guidelines would put those individuals in the “rent-burdened” category.

Sharing a two bedroom brings that number down to 20.2 percent of median income, and a three-bedroom to 16 percent, according to an analysis by Trulia.

Sharing a two bedroom brings that number down to 20.2 percent of median income, and a three-bedroom to 16 percent, according to an analysis by Trulia.

Put another way, New Yorkers save 40 percent when splitting a two-bedroom and 50 percent when splitting a three-bedroom instead of renting a one-bedroom apartment. That was the biggest saving out of the 25 markets that Trulia analyzed — but it’s certainly a phenomenon unique to coastal cities like Miami, Seattle and San Francisco, where rent is higher, and there’s a higher concentration of single, professional millennials.

And wealthy millennials are in part to blame. Over 12 percent of millennials in New York rake in six-figure salaries, and many more don’t even pay the rent themselves. Gift Saengpo-Reger, a broker at brokerage and roommate matchmaking platform Nooklyn, said many of her clients have financial support from their parents.

Daniel Parker of the brokerage Hodges Ward Elliott analyzed renter demographics in South Williamsburg and said that the renters with roommates in that area are “getting to be more mature.”

“They have good jobs, they’re making more money, but are living in neighborhoods where because of rents, they’re sharing with a roommate,” Parker said.

Julia, who did not give her last name for this story, is one such renter. She’s 36 and moving from Columbus, Ohio, to New York this summer. She’s looking for an apartment to share with her 33-year-old co-worker. “I’ve lived alone in a two-bedroom apartment for four years, but that’s just not possible here,” she said.

While budget is often the primary reason for choosing to share, cultural factors contribute as well. With millennials staying single longer and getting married later, the family unit is evolving.

“There’s a huge change in the composition of households,” said Paula England, a sociologist at New York University. Many more people are living alone, sharing with unmarried partners or living in what sociologists call blended families. That includes single dads who don’t live with their children, and unmarried partners where one partner has a child.

Stephen Conroy, a housing economist at the University of San Diego, told TRD that millennials are living the legacy of the Great Recession, which explains why they are taking longer to follow the traditional path of marriage and homeownership. Not only did they begin their careers in a rough market and are thus several years behind, but their experience of job insecurity continues to inform their choices, he said.

“Don’t forget that when you’re buying a house you’re not just going to think about your current income, but the next five to 10 years,” Conroy said. “It takes a little while for people to internalize a new reality.”

Others point to preference and say that living alone isn’t everyone’s ideal.

“People are electing to live with roommates so they have a sense of community in their home,” said Moiz Malik, co-founder of Nooklyn. “If you’re not in a relationship or starting a family unit, those roommates become your new family.”

Anamaria Rojas, a 27-year-old communications specialist at the fitness company Tough Mudder, is looking to move out of a three-bedroom in Downtown Brooklyn with one of her roommates.

One Saturday, Rojas toured a sunny new-development building along Fulton Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant with Saengpo-Reger of Nooklyn.

And for Rojas, like many other women moving to New York’s burgeoning neighborhoods, budget is not the only thing on her mind. “I want a roommate,” she said. “I want someone to come home to.”

According to data from Nooklyn, almost 60 percent of its platform’s users — which focuses on Brooklyn in particular — are women. Malik said that after budget and transportation, safety is a huge factor. “Having someone who is thinking about you when you’re on your walk home, is going to make sure you come home that night, is a huge part,” he said.

Similarly, data from Trulia showed that women between the ages of 28 and 32 saw a 16 percent increase in living with roommates from 2009 to 2015, while men saw a 1.3 percent increase.

But not everyone agrees that having a community to come home to is a motivation to share. “New York is a very populous place,” said Jordan Sachs, the CEO of Brooklyn-centric brokerage Bold New York. “If you’re [worried about being] lonely, you can just stand outside.”

It’s also not always the case that renters have to take on roommates because of budgetary constraints . Sachs estimates that the average cost of an apartment share ranges from $1,500 to $2,000 per room in Manhattan and $1,200 to $1,600 in Brooklyn. At the higher end of that price range, there are certainly options that don’t require sharing, and that’s where other considerations — a shorter commute, better coffee shops, rooftop access and a roommate to come home to at night — come into play.

But when it comes to co-living spaces run by startups such as WeLive and Common, the pricing does not cater to the budget-conscious (see story on page 70).

Co-living may not be the answer, but landlords and developers are thinking of new ways to cater to the market as the culture around sharing evolves.

Parker, of HWE, said most multifamily investors will try to reconfigure the bedroom count if possible. In Hamilton Heights, for example, where the prewar buildings are larger, investors might move the kitchen into living room to make space for an extra bedroom, Parker said. Where a true two-bedroom might rent for $2,500 to $2,800, converting it to a three-bedroom can bring in $3,100 to $3,400 a month.

Sachs said that most ground-up developers create as flexible a design as possible, to accommodate all types of living situations. All of the apartments at 1409 Fulton Street, where Rojas toured a unit, were one-bedrooms that could be converted to two bedrooms by throwing up a wall between the living room and kitchen. It would be done in a matter of days, Saengpo-Reger told Rojas.

Jacqueline Urgo of the Marketing Directors real estate advisory firm said that catering to the share market is similar to targeting millennials more generally, since the two groups overlap. That could mean different amenities, such as gaming rooms and roof decks instead of kids’ rooms or a brandy lounge, and open-plan apartments with small bedrooms and more communal areas.

For Urgo, the ideal is to attract college and postcollege renters to buildings including the Forge in Long Island City and House39 in Murray Hill, with the idea that they’ll fall in love with a space and remain even as they graduate to the next stage in their lives.

And if the data is any indication, it may be a while before they take the traditional next step towards marriage, home and family.