Now more than ever, the “Spitzer” in Spitzer Engineering refers to son Eliot, the fallen governor who continues his efforts to reinvent himself as a real estate mogul.

Bernard Spitzer, founder of the real estate company that supported his son’s now-sullied political career, died last month from Parkinson’s disease. His will named his youngest son, Eliot, as his successor at the helm of the family firm.

For a company that eschews formal titles, the move symbolically confirms what the industry has known for some time: that Eliot Spitzer has been playing an ever-larger role in running the company since he returned to its office at 730 Fifth Avenue following his resignation as governor in 2008, after he left Albany as a result of a prostitution scandal.

And now that it’s “The Eliot Show,” the company is getting back into large-scale development, a business it hasn’t been in for 25 years.

“We’ve yet to see him really get his hands dirty and build a building,” said Peter Hauspurg, Eastern Consolidated CEO, who met with Spitzer last year to discuss finding high-profile assets to invest in. “I guess that’s what he’s about to do now.”

Second bet on Far West Side

Spitzer recently made a second move on his most visible project, which is planned for the Hudson Yards area, The Real Deal has learned.

A year ago, he paid $88 million to buy a development site at 511 West 35th Street. Then several months ago, he quietly acquired control of a land lease on a plot adjacent to the development site, a move that doubles the project’s development potential.

The second plot, at the northwest corner of 35th Street and 10th Avenue, allows for 172,000 square feet of buildable space as of right. Through a pair of building bonuses available to projects in the neighborhood, that total can be increased to 414,600 square feet.

Spitzer plans to build a hotel with retail and possibly a residential component on the site he owns next door, which holds 414,744 buildable square feet. If combined, the two sites could allow for a large building holding nearly 830,000 square feet — a project that would plant the Spitzer name in one of the city’s hottest new neighborhoods.

An active developer in the area, Jorge Madruga of Maddd Equities, purchased a 99-year-lease on the corner property earlier this year for $62 million. Neither Spitzer nor Madruga would comment, but a source unconnected to either said Spitzer now controls the site.

An active developer in the area, Jorge Madruga of Maddd Equities, purchased a 99-year-lease on the corner property earlier this year for $62 million. Neither Spitzer nor Madruga would comment, but a source unconnected to either said Spitzer now controls the site.

Spitzer also hired the law firm Sheldon Lobel, which specializes in land-use and zoning matters, to lobby the Department of City Planning regarding the portion of the site he owns outright.

The project is a complicated one with lots of moving parts, and something that may be difficult for a first-time developer, but observers say Spitzer has surrounded himself with industry professionals who can pull these kinds of deals off.

Those people include Charles Morisi, the man who served as Bernard Spitzer’s right-hand man for more than 25 years, and Jeffrey Moerdler, an attorney at the firm Mintz Levin who has advised Spitzer Engineering for a similar period of time.

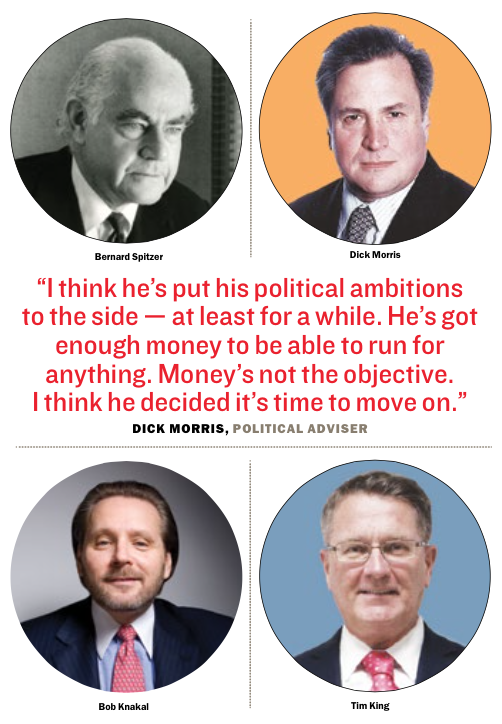

He’s also working with Bob Knakal, the Massey Knakal chairman who brought Spitzer the deal for 511 West 35th Street. Knakal said he’s “always looking for sites for Eliot.”

“He’s clearly a very smart guy,” said Tim King, managing partner of the Brooklyn-based commercial brokerage CPEX. “All the smart people I know typically surround themselves with the kinds of people who can make whatever needs to happen, happen.”

Spitzer also went into contract earlier this year to buy a large development site on the Williamsburg waterfront, a long-stalled project with an affordable-housing component that comes with a different set of potential stumbling blocks.

“Anything involving waterfront has its own challenges,” King said. “But if there are challenges, then there are benefits. From what I’ve seen so far, I think they’ll do very well.”

Reinventing himself

Since leaving Albany, Spitzer has tried his hand at several endeavors. He began penning columns for the online magazine Slate and served as an adjunct professor from 2009 to 2012 at City College, his father’s alma mater, teaching political science courses.

Spitzer also had unsuccessful stints hosting shows on CNN and the former Current TV, and briefly threw his hat back into the political arena with failed bid for New York City comptroller last year.

But now, with a pair of large development projects in the works, Spitzer appears set on making his name in real estate, an industry that he has eschewed for most of his life.

“I get the impression it’s sort of an afterlife,” said political adviser Dick Morris, who worked with Spitzer for more than 10 years and ran his two successful campaigns for attorney general. “I think he’s put his political ambitions to the side — at least for a while. He’s got enough money to be able to run for anything. Money’s not the objective. I think he decided it’s time to move on.”

Morris, whose father Eugene was an attorney who counted the likes of Donald Trump, Sam LeFrak and Bernard Spitzer as his clients, said the son inherited a few of his father’s character traits, including his driven personality.

“They’re both very disciplined and very goal-oriented, and they can be somewhat harsh to those close to them in pursuit of their objectives,” Morris said. “Neither has a soft touch.”