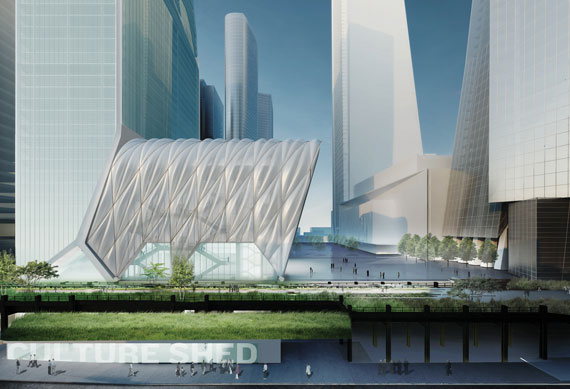

The Hudson Yards Culture Shed, a yet-to-be-built arts and performance space at 10 Hudson Yards, just might wind up being the Batmobile of buildings. Dormant, it’s a glassy fortress. Animated, it will be able to extend its wings so-to-speak by sliding out a retractable exterior as a canopy.

The design is a window into the future of New York City construction — and the role technology will play. This isn’t to say that a fleet of moving buildings will invade New York anytime soon, but the projects of the future will be smarter, more adaptive and, of course, more awe-inspiring.

“I think you’re going to start having more and more facades that are more kinetic, that react to the environment,” said Tom Scarangello, CEO of Thornton Tomasetti, a New York-based engineering firm that’s working on the Culture Shed.

For example, Westfield’s Oculus, the World Trade Center’s new bird-like transit hub, features a retractable skylight whose function is more symbolic than practical: It opens only on Sept. 11.

As a whole, developers are moving away from the shamelessly reflective glass boxes of the past, instead opting for transparent-yet-textured buildings as well as slender, soaring towers à la Billionaires’ Row.

They are already beginning to experiment with different building materials, such as trading steel for wood in the city’s first “plyscraper,” which is being planned at 475 West 18th Street. And, sources say, developers will continue to find new ways of using a building’s “skin” to do some of the expensive work of heating and cooling, partly by allowing buildings to “breathe” through ventilated facades.

New York’s future buildings will also take less time to construct and design — through 3D modeling — with the click of a mouse.

On the most basic level, these innovations are being driven by a necessity to deal with the city’s aging office stock. Much of Manhattan’s office space was built before 1970, a fact the business community argues puts New York at a disadvantage compared to other global cities such as Hong Kong and London.

In addition, many of today’s aging buildings have antiquated heating and energy systems.

In 2014, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city would aim to reduce its greenhouse emissions by 80 percent by 2050, building on Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s goal of 30 percent by 2030.

Vishaan Chakrabarti

From a marketing standpoint, it’s also increasingly difficult for outdated office inventory, usually featuring low ceilings and intrusive interior columns, to compete with today’s modern buildings. Companies — whether they’re law firms, banks or media firms — are often looking for high ceilings, open space and ample natural light. The buildings that will dot New York’s future skyline will incorporate these qualities, through new design and innovation, but some experts predict they will also return to old-school prewar aesthetics, like brick and operable windows.

“There’s a desire for these buildings not to be hermetically sealed boxes,” said architect Vishaan Chakrabarti, who previously worked at the Lower Manhattan-based architecture firm SHoP but just opened his own firm, Partnership for Architecture and Urbanism. “It’s kind of a back-to-the-future moment where we discover what was great about our buildings.”

With help from some of the city’s biggest developers, architects, construction executives and engineers, The Real Deal examined several key industry trends that will be the epicenter of change in the not-so-distant future. Think of it as an early rendering.

Onward and upward

Competing for height is in New York City’s blood.

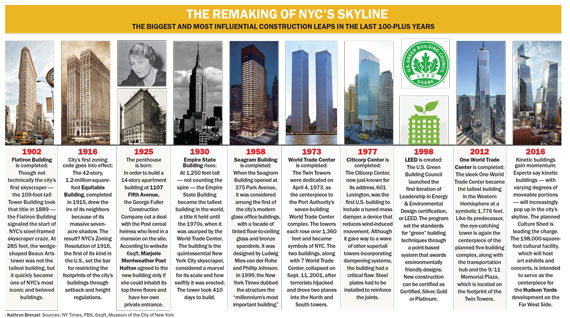

Since the early 1900s, with the advent of steel frames, developers have attempted to set height records with their buildings.

The 792-foot Woolworth Building, which opened in 1913, was the city’s tallest tower until 1930, when it was surpassed by the Chrysler Building at 1,046 feet. That was followed by the Empire State Building at 1,250 feet in 1931, and then the first World Trade Center at 1,368 feet in 1973.

Today, Extell Development Company’s Central Park Tower is poised to be the city’s tallest — save, symbolically, for One World Trade Center — at 1,555 feet. But developers’ mad dash to one-up each other could lead to a new (and even taller) wave of supertalls.

Making it all possible are leaps in construction technology.

A rendering of the Culture Shed, a planned cultural venue at Hudson Yards

Reinforced concrete — a composite of concrete and a pliable material, often steel — has become stronger and allowed developers to move away from exterior support columns. This means the building’s core bears the bulk of the responsibility of keeping the building upright, while the facade can be entirely glass with unobstructed views.

JDS Development is incorporating concrete with a 14,000-pounds-per-square-inch compression strength at 111 West 57th Street, its “skinny” condo tower that’s set to top out at more than 1,400 feet. One World Trade Center also features concrete with the same degree of strength. By comparison, 10 years ago, the strongest concrete used in buildings in the city was 10,000 pounds per square inch.

Looking ahead five to 10 years, concrete and steel are likely to see a 50 percent increase in strength, according to Stephen DeSimone, who runs the structural engineering firm DeSimone Consulting Engineers.

This evolution will usher in towers that reach 2,000 feet or even 2,640 feet — a half a mile — DeSimone told Crain’s last July. That’s about two Empire State Buildings stacked on top of each other.

While it may sound outrageous, it’s not out of the question. Dubai’s mixed-used Burj Khalifa — which opened in 2010 and is currently the world’s tallest tower — rises 2,716 feet. And, Saudi Arabia’s planned Jeddah Tower is expected to best that at 3,280 feet.

“There’s really no technical limitation,” said Jason Gabel, spokesman for the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. “Really, the limit is, is there going to be enough money for these projects?”

Indeed, just because it’s possible to build taller, doesn’t mean New York developers will do it. The demand for uber-luxury properties here is already not quite matching the supply, threatening an over-saturation of the market.

A rendering of Extell Development’s Central Park Tower, which will top out at 1,550 feet tall when it’s complete in 2019.

The other impediment is One World Trade Center. Extell’s original renderings for Central Park Tower whipped up controversy when they showed the project would likely exceed the World Trade Center’s 1,776 feet. Following some heavy public backlash, the firm’s latest renderings dropped the project’s contentious spire.

“There’s kind of an unspoken agreement that One World Trade Center will not be surpassed in height,” Gabel said. Whoever attempts to dwarf it will have to have a pretty compelling argument, he said.

Joseph Maraia, executive vice president of construction giant Lend Lease, said that after 1,000 feet, other factors also come into play. For instance, it becomes more difficult (and expensive) to transport materials to the top of buildings during construction. While that and other challenges won’t necessarily deter New York developers from reaching greater heights, they mean that the buildings might not make financial sense.

“There comes a point of diminishing returns,” said Maraia, whose firm is working on several of the city’s under-construction supertalls, including 432 Park Avenue. “It remains to be seen if it will be cost effective to go above the 1,500 feet that we’re playing [with at] the latest rounds of supertalls.”

Of course, a central motivator for developers is the price that these stratospheric properties can fetch. Last January, a penthouse in Gary Barnett’s One57 busted the city’s record for priciest condo sale when it closed at $100.5 million.

Extravagant penthouses elsewhere in the world — like one listed for a reported $400 million in Monaco — could inspire developers to aim even higher.

However, David Farnsworth, a principal at global engineering firm ARUP who leads the firm’s tall buildings team in the U.S., predicted that 432 Park would hold the residential height record for at least the next 10 years.

On top of the wavering demand, there’s a limited amount of Manhattan land that can handle supertall towers, since the taller a building soars, the more space it needs at its base. Farnsworth said developers are likely to continue to test the limits of slenderness and said buildings will continue to do “crazy gymnastics” to optimize space, like cantilevering over adjacent properties where the developer has scooped up air rights.

On top of the wavering demand, there’s a limited amount of Manhattan land that can handle supertall towers, since the taller a building soars, the more space it needs at its base. Farnsworth said developers are likely to continue to test the limits of slenderness and said buildings will continue to do “crazy gymnastics” to optimize space, like cantilevering over adjacent properties where the developer has scooped up air rights.

There are other challenges associated with height.

Buildings have been getting lighter, necessitating devices that hedge the swaying impact of wind on buildings. So-called dampening systems act as counterweights to a building’s sway and are being used on the city’s slender skyscrapers, like 111 West 57th, 432 Park and 220 Central Park South. A “tuned mass damper,” for example, is a steel or concrete weight mounted at the top of the building to resist the tower’s movement, while “slosh tanks” use tanks of water for the same purpose.

A rendering of B2 BKLYN

While dampers don’t make the headlines, they are key players in a developers’ quest for greater heights and will likely become even more commonplace in New York construction going forward.

Forest City Ratner, for example, is installing a new type of damper at B2 BKLYN, the first residential tower at the high-profile Pacific Park project, to counterbalance its lightweight, modular construction. The technology, known as a “fluid harmonic disrupter,” consists of a series of water-filled pipes at the top of the building. It was originally developed by NASA in 2009 to absorb vibrations strong enough to detach an astronaut’s retina. But in the real estate industry, it’s now being billed as a lighter and smaller solution to reduce wind-induced vibrations.

In some ways, the success of the city’s supertalls depends on these dampening systems: Residents at the top of these towers are the most affected by a building’s sway. And if there’s sway, they may not pay eight-or-nine-digit price tags — even if they get a spectacular view. “As buildings get taller, and also lighter, it makes the accelerations you may feel even more an issue,” said Thornton Tomasetti’s Scarangello, who is also working with Forest City on B2.

Skin in the game

A lot of the innovations in building design are being incorporated into exteriors — meaning that much of the city could have a far different look 10 or 20 years from now.

Over the past decade, low-iron glass has been used to create transparent buildings. Now, new features are making the exterior more integral to how a building functions.

“We’re seeing a lot of emphasis on getting more to happen at the building’s skin,” said Brian Stacy, principal at ARUP, whose work includes the Fulton Street Transit Center and Columbia University’s Jerome L. Science Center.

For example, at the Related Companies’ massive Hudson Yards development, low-emission coatings on glass are being used to maximize visible light while assuring that the buildings aren’t overheated. That means that during the summer, the glass ensures that heat is reflected from the building, while during the winter, it prevents heat from escaping.

A rendering of Hudson Yards

“It’s literally microns thin, but it makes a huge difference to us,” Stacy said, adding that he expects an increasing number of buildings to incorporate low-emission glass going forward.

Architects and developers are also being more strategic about where they’re using glass.

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and Tribeca Associates flanked the north and south sides of the Baccarat Tower — the hotel and condo on 53rd Street — with glass facades while covering the east and west sides in metal panels.

TJ Gottesdiener, managing partner at SOM — which also designed One World Trade Center — said the glass was applied to the sides with the best views and the greatest amount of sunlight. Those types of strategies will become more popular in the future, he said.

Meanwhile, at the Culture Shed, which is still in the planning stages, Related is using a transparent plastic called ethylene tetrafluoroethylene that’s increasingly being employed in building facades instead of glass because it provides better insulation and is lighter and less expensive, according to Scarangello.

The building is also kinetic, meaning it can change its form to accommodate different kinds of performances. The structure, which includes both a stationary portion and a moveable portion, has a retractable roof that can roll out in order to create a larger space for film screenings, musical performances or art exhibits.

Rob Otani — who leads Thornton’s special-structures unit and is currently working on Cornell Tech’s new campus on Roosevelt Island — said that whole buildings are not likely to be kinetic since that would require considerable maintenance that few developers would be willing to take on. But kinetic facades will likely be incorporated into more designs, he said. This means exteriors that respond to the environment, shifting in response to the sun or blocking high winds. The Milwaukee Art Museum, for example, features a wing-like Brise soleil — a sun-shielding structure designed by Santiago Calatrava, the architect behind New York’s Oculus — that opens during the day and closes at night or during bad weather.

More (outdoor) play

While many of today’s new residential buildings incorporate private penthouse terraces or communal rooftops, they are just scratching the surface when it comes to constructing towers with outdoor space.

“There’s going to be a time in New York City where living without a substantial outdoor space is just going to be unacceptable. It’s going to be like living in the suburbs without a backyard,” Eran Chen, founder of ODA New York, told TRD. “All these towers that don’t have them are going to lose their value.”

Chen is already testing new ways to achieve that goal.

At the residential project at 303 East 44th Street that ODA is designing for developer Triangle Assets, it carved out open space by creating 16-foot-high gaps supported by ligament-like columns. The gaps contain private gardens for 11 units in the 41-story building, starting on the 23rd floor. The design maximizes outdoor space, while also achieving a striking (and futuristic) effect.

Scarangello said keeping the inside of the space efficient is key when adding outdoor space. “People want to live in apartments and work in offices where the interior is very functional,” he said. “So I think what we’re seeing is people are using the facade to create drama, [but] not twisting the building into a pretzel in order to create drama.”

Eran Chen

And going forward it will not just be residential buildings getting serious outdoor space. It will eventually become the norm for office towers, sources say.

Michael Samuelian, vice president of Related, said almost every major office tenant at Hudson Yards will have their own outdoor terrace. Other office buildings are likely to follow suit. “We haven’t really been keeping pace with the rest of the world when it comes to creating new office space in New York,” Samuelian said. “Hudson Yards represents the future of office space in New York.”

Rick Cook, founder of the architecture firm CookFox, which is designing 550 Vanderbilt in Pacific Park, said architects will increasingly turn to biophilic designs, which emphasize the bond between humans and nature. Green walls and roofs, covered in vegetation, can help collect and store rainwater, cool a building or shade glass curtain walls and cut down a building’s overall carbon footprint, he said.

The roof of CookFox’s Chelsea office, for instance, is a sea of greenery. Employees harvest their own honey at the office’s private beehive.

“It’s just an amazing thing to watch when you create a framework for nature to take off,” Cook said. “You’re not going to see any tech that’s more complex than what nature does in front of our eyes all the time.”

Speed = consolidation

As developers seek out bold innovations, there’s a huge challenge hanging over the industry: Will there be enough construction workers to carry out these new high-tech designs in the future?

“There are just not enough contractors and skilled workers to go around,” said Bob Barone, senior managing director of CBRE’s valuation and advisory services construction management group. “Anytime we’re in a deep recession there’s a percentage of people who leave and leave forever.”

The 2008 housing crisis, coupled with the earlier economic downturn in 2001, quashed new construction in the city, forcing many experienced designers and construction workers to flee the industry, said attorney Barry LePatner, who specializes in construction.

Construction employment hit a 13-year low in 2011. After three years of consecutive growth, it’s now slowly recovering, with the New York Building Congress reporting 121,200 private-sector jobs in the first quarter of 2015, compared to 128,300 in the first quarter of 2008.

Still, as a deluge of new projects floods the market, there is a dearth of experienced professionals.

“Today we see a shortage of people with seven to 15 years of experience at every level of the industry,” LePatner said. “We’ve lost almost half a generation in the design and construction world that has not been made up.”

That labor shortage is one of several issues that have prompted developers to acquire construction companies and suppliers, such as glass and crane firms. Doing so not only allows developers to assert more control over their projects, in terms of cost and available resources, it also means they will always have workers on hand.

Developers are seeking to “control their destiny by controlling the supply chain,” said Maraia, of Lend Lease, which is itself getting into the New York development game (see related story on page 50).

“I think a lot of the big developers have gone down that route, and I would expect that we’d see others follow in their footsteps,” he said.

These cross-industry consolidations are a mounting trend that experts say will redefine how the New York development and construction industries operate. A developer will likely wear many hats — construction manager, manufacturer and designer.

It’s already happening. Related opened a facility in Pennsylvania this summer that will produce the curtain walls being used at Hudson Yards and its other projects. The move was a response to months of delays on glass panels intended for the developer’s Hunter’s Point South project in Long Island City.

“With the logistical issues, small number of producers and growing costs, we’d rather bet on our ability to domestically produce and control the supply,” Bruce Beal, Related’s president, recently told the Wall Street Journal.

In other words, who needs to hire a company when you can just buy one or create one?

Joe McMillan, the CEO of DDG — which has developed projects such as 345 West 14th and 12 Warren streets — and JDS’s Michael Stern also said they believed that developers would continue to buy more construction-related companies in the future. Both firms are ahead of the curve on that front.

A rendering of the residential project at 303 East 44th Street

For the last six years, DDG has designed, developed and built all of its own projects. McMillan said doing so gives the firm control over the “whole life cycle of the project.”

Similar to DDG’s model, JDS does all of its construction in-house. “There’s an efficiency to it,” Stern said. “We like having the same people at the design table who are going to build the building.”

Technology is also enabling developers to plan and envision their buildings in a more detailed fashion as well as better estimate a project’s bottom line. The industry is increasingly using Building Information Modeling, a process that involves creating 3D digital representations of projects that test materials and designs to provide a clearer picture of a building’s potential cost and appearance.

At the Barclay’s Center, for example, digital modeling enabled the designers and developers to figure out the dimensions of thousands of glass panels without having to draw each individually, said Chris Sharples, principle at SHoP, which designed the stadium. Since it’s digital, there is more real-time communication, McMillan said.

“The days of paper planning are largely behind us,” he said.

Modular’s mission

Asked about the future of modular, Susan Hayes, head of Forest City’s modular division, recently told TRD, “I feel like I’m sitting at the base of a rocket ship here. People are looking for something new and better.”

It’s a bold statement considering the circumstances. As a construction trend, modular has gone from being a possible savior to at risk of being an overhyped fad.

When Forest City announced in 2012 that it would build the world’s tallest modular steel tower at Pacific Park, then named Atlantic Yards, the company said it had “cracked the code” of prefabrication, a construction method that could halve construction costs and shave at least six months from building schedules.

It was also billed as a boon for the city, since it would bring affordable housing units — 50 percent of the 363 apartments in B2 BKLYN — to market quickly.

But things didn’t go as planned.

Construction halted in August 2014 after only 10 floors had been installed. In dueling lawsuits, Skanska — who co-owned the modular factory with the developer — and Forest City blamed each other for tens of millions of dollars in cost overruns.

Forest City ended up buying out Skanska’s stake in the factory. It commenced construction on the tower in December 2014, the month it was initially supposed to be finished. B2 is now slated for completion in the third quarter of 2016.

More ominously, Forest City recently announced it might have to lay off more than 200 employees from its modular division if it isn’t hired for additional projects over the next few months.

Hayes, however, said the warnings about potential layoffs are not an “indication of a lack of interest” in prefabrication but are just part of the natural “ebb and flow” of business. She anticipates that modular construction will become a mainstream method for multi-family homes, hospitals and dormitories in the next five to 10 years.

While many agree that the building method is far from dead, the verdict is still out on how widely used it will be in New York.

Experts who spoke to TRD seemed confident that modular construction has a future in the city, if not for entire buildings then for parts of projects.

Lend Lease’s Maraia said prefab bathrooms could be 10 percent cheaper than constructing a bathroom from scratch. But, he said, the difficulty in transporting large prefabricated materials throughout the city will likely impede the proliferation of full-building modular construction.

Other developers are taking a wait-and-see approach.

“I think modular construction is very interesting, and I think on a certain scale, you’ll see it become more popular,” Stern said, adding, “I’m definitely intrigued by it, and I think I’m going to keep an eye on it, but I’m not going to be the pioneer.”