There’s an eyebrow-raising issue playing out in the private equity world right now. While funds have pulled back on the amount of money they’re pouring into real estate deals, they’re also looking to raise more money than ever for new deals.

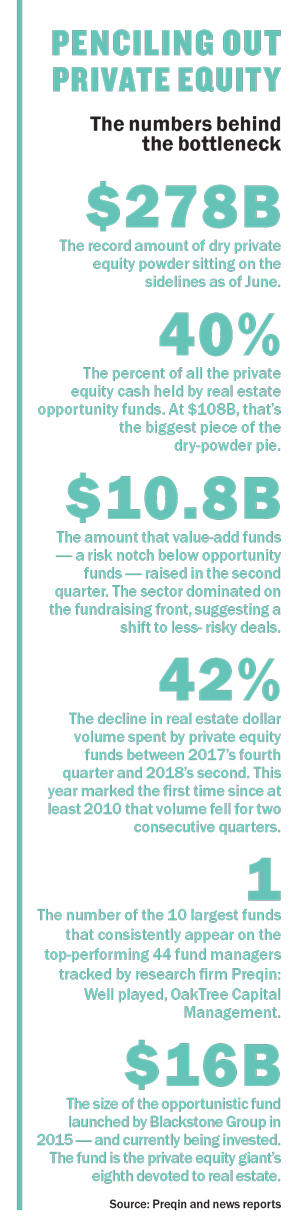

And those fundraising efforts come on top of a record amount of dry powder already sitting on the sidelines. Private equity research firm Preqin pegged that dry- powder figure at a record $278 billion at the end of June.

Meanwhile, the opportunistic deals that many funds are searching for are still rare, property valuations are high, competition is stiff and interest rates are rising.

“All this capital’s been raised, and now it’s potentially a sort of tricky time to put it to work,” said Tom Carr, head of Preqin’s real estate group.

And the numbers are starting to reflect that skittishness.

Real estate deal volume among private equity firms declined in 2018’s first two quarters following a peak at the end of 2017, according to Preqin. That marks the first time since at least the beginning of 2010 that the number of transactions fell for two consecutive quarters.

Nonetheless, funds are aggressively hunting for even more cash.

In July, there were 624 investment vehicles looking to raise a record $206 billion.

And since funds have been so active in selling assets over the past several quarters, they’ve been redistributing the proceeds from those sales back to investors, Carr said.

That means that those investors, who are still eager to deploy their capital, are in play for other funds.

“You always sort of get the impression that if investors are willing to put money in, then managers will be willing to raise,” said Carr.

“You always sort of get the impression that if investors are willing to put money in, then managers will be willing to raise,” said Carr.

However, he added that funds could increasingly branch out to different regions or segments of the market in their quest for stronger returns.

“In certain areas it’s definitely very competitive,” he said.

Rethinking risk

The biggest chunk of private equity money in real estate has long targeted opportunistic, high-risk investments with big payoffs — often for fix-and-flip properties.

In July, opportunity funds held about $108 billion in capital — or 40 percent of all the private equity money earmarked for real estate. That was the largest percent of the dry-powder pie.

But investors are starting to show signs that they have less of a stomach for those kinds of deals.

That’s partly because those opportunistic investments tend to do better during the earlier, high-growth times of the real estate cycle, experts said. In New York, that time was in the early years of the recovery starting in 2010, and is now a distant memory.

Toward the end of a cycle — which many economists have long predicted the New York market is already in — less-volatile investments with guaranteed revenue streams (such as fully leased office buildings with at-market rents) tend to attract more investors.

Sources say that the private equity world is also roiling now because too much money has been allocated to opportunistic funds during this cycle. Since the deep correction those funds were banking on has yet to come, there is a massive shortage of those deals to go around.

“I would imagine that certain groups tried to get ahead of the potential downward trajectory,” with the goal of investing in opportunistic assets when the market started falling, said Mo Beler, head of investment sales in New York for JLL.

But, he noted, “that simply has not yet occurred in New York.”

Beler said that of the about 40 Manhattan office buildings on the market, only seven could be considered value-add investments.

With these deals so few and far between, private equity funds are starting to rethink their strategies.

During the second quarter, funds seeking value-add investments — a notch below opportunistic investments in terms of risk — dominated on the fundraising front. They pulled in nearly half of the $22.4 billion raised during the quarter.

And managers are increasingly raising funds focused on debt, a space many investors are turning to as a risk-adjusted alternative to pricey equity stakes.

For example, the Midtown-based Cerberus Real Estate Capital Management and TCI Real Estate Partners — the property arm of London’s Children’s Investment Fund — are raising some of the biggest funds in the market at $4 billion and $3 billion, respectively.

Blackstone president and COO Jonathan Gray

Meanwhile, GreenOak Real Estate closed a $1.55 billion value-add fund in the second quarter. It’s the third private equity fund for the firm, which was founded in 2010 by a trio of former Morgan Stanley real estate executives.

Over the past two years, GreenOak has been more of a seller than a buyer, but now it’s changing its ways as it’s finding more reasonably priced deals. And the company is looking beyond its core markets, mainly in New York and San Francisco, to places such as Seattle and Washington, D.C.

The new fund has already made two New York investments. The first is the 464-unit Biltmore rental at 271 West 47th Street, which it picked up with Slate Property Group for more than $250 million. The second is the Gansevoort Park Avenue hotel — which it bought with Highgate Hotels for $200 million and has rebranded as the Royalton Park Avenue.

In May, GreenOak partner Sonny Kalsi told Bloomberg that he sees hotels as an area of opportunity in New York.

“We had been nervous about oversupply in New York but now feel like the market is close to or at the bottom and that there are pockets of good value,” he said.

Small, but mighty

With so many funds looking for investors, competition is intense. But capital is increasingly concentrated among fewer firms.

“The bigger guys are raising more money, and a lot of smaller guys are not raising what they were able to,” said Michael Rotchford, co-head of the capital markets group at Savills Studley. “Pension funds and other institutional investors continue to sharpen their focus on the number of managers they want to have at any given point in time.”

Meanwhile, institutional investors — such as insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds — have for some time been limiting the number of funds they work with as a way to keep fees down. That’s shifted the balance of power from funds to investors, who have more leverage when it comes to negotiating fees and other terms.

But while larger funds may be having an easier time raising money, bigger is not always better for real estate private equity — at least on a dollar-for-dollar basis.

Major private equity players, including the Blackstone Group, Lone Star Funds and Brookfield Property Group, have several billion dollars at their disposal at any given time. But the smaller funds actually tend to generate better returns.

Of the 44 consistently top-performing fund managers tracked by Preqin, only one — OakTree Capital Management — appears on the company’s list of the 10 largest fund managers.

Smaller companies such as the Philadelphia-based Arden Group — which launched its private equity fund business in 2012 — regularly rank in the top tier of managers.

Here in New York, Arden signed a contract in July to buy the Viceroy Hotel on Billionaires’ Row for $41 million from the now-liquidated New York REIT — a steal compared to the $149 million the seller purchased it for in 2013.

And last year, Arden launched its first debt vehicle: a $300 million fund that in May provided a $34 million condo inventory loan to JDS Development Group’s 613 Baltic Street in Brooklyn.

Other top-performing funds include TH Real Estate — the property arm of the mega asset manager TIAA — which is now unloading assets in New York. The company is shopping its 49 percent stakes in 470 Park Avenue South and 8 Spruce Street, as well as the Midtown office property at 730 Third Avenue.

Blackstone, meanwhile, is currently investing its eighth real estate private equity fund — a $16 billion opportunistic vehicle launched in 2015.

But the company, the world’s largest real estate private equity fund manager, is looking overseas amid concerns about interest rates in the United States.

Blackstone president and COO Jonathan Gray told CNBC in July that interest rates are “one of the headwinds here in the United States” compared to Europe, where they are expected to stay lower longer.

“We found the investment environment, on balance, a little bit better,” in Europe, despite the fact that U.S. economic growth is stronger, Gray said.

On a July earnings call, Gray also said the company is getting ready to launch its newest global real estate fund, which could close by the end of the year.

A spokesperson for Blackstone declined to comment further.

But investors, especially those in high-risk opportunistic funds, have been asking for vehicles with longer life spans.

Tim Bodner, head of the real estate private equity group at PricewaterhouseCoopers, said investors are trying to figure out what to do with the capital that’s been returned to them.

“To some degree, it’s hard to reinvest that capital and get the same level of return they may have gotten on a prior fund,” Bodner said. “Having that capital tied up for a longer period of time means a lower return, but it takes away some of the risk of having to reinvest it.”

There may also be larger systemic changes that could shake up the way investors and managers are allocating dollars.

David Eyzenberg, founder of the Manhattan-based commercial real estate investment-banking firm Eyzenberg & Company, predicted an increase in demand for safer investments because of broader demographic changes.

As baby boomers retire and the defined-pension plans that they draw down from look to invest more money, Eyzenberg said investors will be less concerned with monster returns and more interested in stabilized properties that produce what’s akin to a stock dividend. “It’s not about me getting a pop on my money. I can do that buying Apple or Amazon,” he said. “What I need is a current return.”

“There’s probably a lot more demand from investors on a global basis — from the grandmother in Ohio to the sovereign in Dubai,” he added. “They want stable, current returns. And there’s probably much higher demand for that, and that’s probably where a lot of that money is going to be going.”