Let’s face it. Stories about people’s taxes don’t typically lend themselves to juicy scoops for journalists. The federal IRS code is complex and confusing even for the most erudite tax specialists. And given the privacy of individual filings, the facts can be difficult to nail down and will likely involve making a presumption that no one other than the person in question, and his or her accountant, can confirm.

Still, when the New York Times revealed that Republican nominee Donald Trump posted a staggering personal loss of $915.7 million in 1995, it was the biggest story of the 2016 election campaign season.

In this case, the critical presumption, which Trump did not refute, was that the developer had not paid any income tax for 18 years, because losses can cancel out future income.

The ultimate takeaway, however, was that property investors are notoriously good at working the tax code to their advantage. As reported in the Washington Post, the average firm in real estate development pays just over 1 percent of its income in taxes, according to data compiled by Aswath Damodaran, a professor at New York University. Compare that to the average for all industries, which is almost 11 percent.

This past month, The Real Deal spoke to tax accountants, attorneys and industry sources to learn how real estate investors most commonly game the tax code. What we discovered is that typical maneuvers like switching from condos to rentals, leveraging land into an ownership stake in a development, and even refinancing a property all have tax implications. While it’s impossible to deduce the precise tax strategies at play, it is clear that opportunity abounds.

It helps that the U.S. government has flip-flopped over the years on the way it views real estate as an investment vehicle. For example, in 1986, Congress passed a law that treated virtually all investments in rental real estate properties as passive investments, much like stocks or bonds. This meant property owners could no longer deduct any operating losses on their properties from their taxable income. However, in the following years, property prices went into a tailspin and legislators changed the rules again to allow rental property owners to deduct operating losses on their properties from their taxable income, provided they spend at least half their working hours and at least 750 hours a year as a real estate professional.

It helps that the U.S. government has flip-flopped over the years on the way it views real estate as an investment vehicle. For example, in 1986, Congress passed a law that treated virtually all investments in rental real estate properties as passive investments, much like stocks or bonds. This meant property owners could no longer deduct any operating losses on their properties from their taxable income. However, in the following years, property prices went into a tailspin and legislators changed the rules again to allow rental property owners to deduct operating losses on their properties from their taxable income, provided they spend at least half their working hours and at least 750 hours a year as a real estate professional.

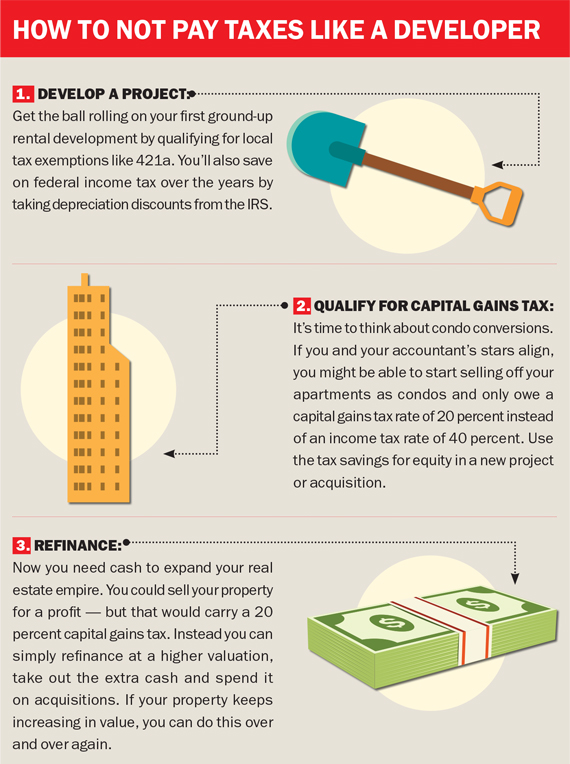

Depreciation, of course, is the most well-known — and counterintuitive — way real estate investors can shrink their tax bill. The IRS treats properties as assets that lose value over time, along with cars, desks and refrigerators. But unlike cars and desks, which actually do become less valuable over time due to wear and tear, buildings in New York City and other major metropolitan markets tend to steadily gain value over the years.

The rules allow property owners to deduct a certain portion of a property’s value every year until that value reaches zero. For residential rental properties, the typical depreciation period is 27.5 years, according to the IRS’ website.

Another way developers can drastically lower their annual income tax bill is through a cancellation of debt, or outstanding debt that has been forgiven after negotiations. Typically, this kind of debt forgiveness is treated as income on a tax bill, but current laws allow taxpayers to deduct this debt if it is tied to Chapter 11 bankruptcy (which Trump entities had undergone four times by 1995) or if the taxpayer is insolvent, meaning that the debt is greater than the total market value of assets.

After selling the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, Hilton Worldwide said it would use the proceeds to buy five new hotels as part of a 1031 exchange.

But even those who don’t meet those criteria have another way out of paying income taxes. In 1993, after Congress passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation act of 1993, underwater real estate moguls with forgiven debt who didn’t meet either of the criteria had a new way to get out of paying income taxes. A line added to the tax code that year allowed canceled debt tied to “real property business indebtedness” to qualify for gross income exclusion, significantly broadening the pool of real estate owners eligible for major tax markdowns.

“It was in response to a crash in real estate, and Congress perceived a need to bail out real estate operators whose properties suddenly lost value and whose debts had to be canceled by banks,” said Richard Beck, a tax law professor at the New York Law School. The canceled debt, Beck said, “created a lot of phantom income” that would otherwise have been taxable.

In part because of the lenient tax code, real estate investors are especially zealous in avoiding or delaying taxes, sources said. After the Times’ story broke, tax services firms sought to seize the moment by sending out email blasts advertising their tax reduction services. One email from South Florida-based Property Tax Appeal Group, titled “Donald Trump Knows How to Avoid Taxes in Real Estate,” urged investors to file property tax appeals and “take advantage of what the law allows.”

“This is truly a win-win situation,” the email read.

New York City players, however, are likely already ahead of the curve. Below are some recent high-profile real estate deals examined through the lens of federal tax rules that make it possible to defer or avoid paying Uncle Sam.

Pivot from condos to rentals

During the development of One57, Extell Development, led by Gary Barnett, initially planned to keep 38 apartments in its condo tower as rentals. Barnett, however, ultimately changed his mind. Citing a weak high-end rental market, he decided to list the units for sale in May 2015 — first in bulk and later one by one as condos.

His decision to sell drew attention mostly for what it said about the market, but the change in strategy also happened to come with a potential tax advantage: Developers typically have to pay income tax on any profits from new-development condos, while sales of rental units — which are considered investment vehicles — are taxed at the far lower capital gains rate, that of 20 percent as opposed to nearly 40 percent.

Fred Berk, co-chair of the real estate group at accounting firm Friedman LLP, said that, in general, property investors are “always trying to turn ordinary income into capital gains. There are simple and complex ways to do that.”

Highlighting gray areas in the real estate tax code, tax attorneys interviewed by TRD disagreed on how Extell could achieve a capital gains tax rate on the sales of the rental units. Some tax experts said Extell would need to keep the units as rentals for five years and then sell them in bulk in order to get capital gains tax treatment. Others said that the developer could sell them earlier and one by one under certain circumstances. Mayer Greenberg, an attorney at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan LLP, wouldn’t comment on One57 but said the IRS typically looks at the developer’s intention: If the developer can credibly claim the plan was to keep units as rentals, he can possibly get capital gains tax treatment on a subsequent sale.

Extell declined to comment.

The developer is by no means the only one shifting to rentals and opening themselves up to such tax benefits. In 2007, the Related Companies broke ground on a 669-foot-tall, 58-story apartment and hotel tower, dubbed MiMA, with a total projected cost of $900 million. The building plans called for 623 rental apartments on the lower floors and 151 condos at the top. But the following years turned out to be a terrible time to sell condos. The housing bubble had just popped, and by September 2008 the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy and ensuing global financial crisis sent the luxury apartment market into a tailspin.

By the time the building was completed in 2011, Related had changed tack and decided to rent out the 151 former condos. It sold the units in December 2015 to Kuafu Properties for $260 million.

Ponte Equities is partnering with Related Companies on the development of 70 Vestry.

While it may have been driven by market timing, the sale of the units could be advantageous taxwise. Again, as with the One57 example, some experts said that because Related had rented out the units for years, the sale could have qualified as a capital gain, whereas had Related sold the apartments one by one as condos back in 2008 or 2009, it would have had to pay income tax on its profits.

Related declined to comment.

On a smaller scale, there are numerous examples of developers buying and holding units in their own developments long enough to qualify for a capital gains tax once they sell. William Zeckendorf, for example, took over a three-bedroom apartment on the 41st floor of his condo development 15 Central Park West in 2005. Five years later, in November 2010, he sold it for $40 million. Provided he did not use the unit as his primary residence, selling the unit after five years becomes a capital gain.

Structure a ‘mixing bowl’

In 2014, Ponte Equities agreed to a $115 million sale of a six-lot development site in Tribeca to Related Companies. Together, the two firms would sponsor one of the most extravagant condo projects ever proposed Downtown, a 46-unit tower at 70 Vestry Street with a target sellout of over $700 million. Having amassed a portfolio of parking garages, warehouses and auto shops in the neighborhood over the years, the Ponte family had in the past partnered with the big development firm. Just this year, the pair completed 460 Washington Street, a 10-story, 140,990-square-foot residential building.

As property owners-turned-developers, the Pontes are among those in the real estate industry who have access to significant tax opportunities. In what’s known in industry circles as a “mixing bowl” transaction, property owners can defer capital gains taxes by contributing land in return for a stake in a joint venture.

In other words, Ponte could have paid no taxes on the $115 million sale of its properties to Related had it used the proceeds to acquire a stake in the project.

“Basically, you get a tax-free exchange of the property,” said one Manhattan tax attorney who has arranged similar transactions in the past for real estate investors. The strategy, the attorney added, is known to “top people, but not necessarily every mom-and-pop lawyer knows how to do it.”

It should be made clear that while TRD found that 70 Vestry is a joint venture between Ponte and Related, it is not known whether the deal was structured as a mixing bowl transaction. Requests for comment by phone and email to individuals at Ponte Equities were unreturned.

Do a 1031 exchange

In 2015, Hilton Worldwide sold the Waldorf Astoria hotel for a record $1.95 billion to the Chinese insurer Anbang. When the sale closed, the hospitality company announced that it would divert the funds from the sale of the landmark Manhattan skyscraper into five new hotels in Florida and California as part of a like-kind exchange, also known as a 1031 exchange. Under this arrangement, any taxes owed on the money used to purchase those hotels could be deferred indefinitely.

The case illustrates how tax tricks aren’t always about not paying the taxes, but instead often about not paying them right now.

“Anybody’s who’s a [serious] real estate investor will constantly be doing exchanges,” said Michael Packman, CEO of the wealth management firm PNI Capital Partners.

Tax-deferred 1031 exchanges nationally exceed $100 billion in property sales annually, according to Packman’s estimates. Joe Koicim, a Marcus & Millichap broker who helps find exchange properties for middle-market investors, says most investors in the market are trying to take advantage of 1031 exchanges, and the numbers are increasing. “Sixty to seventy percent of our [clients] will do exchanges,” Koicim said. Typically, he added, they will do multiple exchanges.

“It’s an amazing tax-deferral mechanism,” said William Timlen, a partner at the EisnerAmper accounting firm, who said the overwhelming majority of his real estate clients have completed these exchanges in the past.

Moreover, investors can delay paying taxes indefinitely by repeatedly doing 1031 exchanges — which, according to experts, is common at the highest levels of the real estate business.

“In real estate, unlike in stocks and securities where you pay tax on your trading gains, you can just keep rolling over, so people do this for decades and decades,” attorney Stephen Land of Duval & Stachenfeld said.

Decades and decades … until the owners die. Because once they do, the accumulated unpaid capital gains tax on years of property exchanges simply disappears. Those years paying no taxes are laid to rest with the taxpayer.

“The old saying in the industry is swap ‘till you drop,” said Packman, “because when you die your heirs get the stepped-up cost basis,” meaning that the tax new basis is equal to the market value of the property, so no capital gains tax is owed at the time of sale because on paper, at least, there was no profit margin.

Not surprisingly, 1031 exchanges have often been the subject of proposed reform or repeal in Washington. President Obama’s proposed budget for 2017 would cap deferrable gains at just $1 million. But other politicians have advocated ditching 1031 altogether.

Brian Sidman, a business partner of Packman in a new venture called Keystone National Properties, which will cater to 1031 investors, warned that abolishing 1031 would “completely devastate not only the commercial real estate economy, but it would even trickle down to the everyday individual that’s holding a hammer.”

Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has not proposed abolishing 1031, but similar to President Obama has included a $1 million deferment cap on 1031 exchanges in her own taxation agenda, a proposal that would return $50 billion in tax revenue in 10 years, according to a September report from the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Refinance

In May, the Paramount Group refinanced its office tower 31 West 52nd Street with a $500 million loan from an unnamed lender. The new mortgage replaced a $413.5 million loan that was set to expire in 2017.

In doing so, Paramount potentially tapped into a tax-free piggy bank: a building that’s rising in value.

Dustin Stolly, a capital markets broker at JLL, said there are many reasons why property owners may choose refinancing over selling. “Tax considerations is one of them,” he said. Property owners who want to benefit from an asset’s increase in market value have two options: They can sell or they can refinance. If they sell (without doing a 1031 exchange), they pay capital gains tax on any profit. Refinancing, however, doesn’t typically count as a “realization event” in the eyes of the IRS, explained tax attorney David Spencer — meaning there is no profit to be taxed.

The flip side of refinancing, of course, is that the loan will have to be repaid. That can be a challenge if the property’s value falls. But in New York City, real estate prices have been rising more or less continuously for decades (with a few dips). This means that property owners who time cycles well can take millions in cash out of their portfolios without paying taxes by repeatedly refinancing at higher valuations. According to Stolly, structuring a portion of a building’s debt as mezzanine debt rather than a senior mortgage is another way landlords can lower their tax bill. Unlike senior debt, mezzanine debt doesn’t carry the 2 percent mortgage recording tax. But the downside, Stolly said, is that mezzanine debt is often easier to foreclose on.

Take a (really) long view

As mentioned, deferred capital gains taxes do not pass on to heirs after an owner’s death, making the strategy of holding property until one dies the ultimate tax escape plan. And despite hefty estate taxes, real estate is still often well positioned to hand down to the next generation, said estate planning attorney Edward Renn of the Withers Bergman firm.

“Real estate is a terrific asset to play with because it usually has predictable cash flow,” Renn said.

Estate taxes, which kick in after the first $5.4 million is passed down to heirs, can be as high as 40 percent, and the myriad ways estate planners and accountants chip away at that liability are not simple. But as with the depreciation of real estate, the game here is to manipulate the estate so heirs can claim it’s worth less than it really is.

“People create entities designed to artificially depress the value of the estate, such as limited control partnerships where you argue that because members can’t easily liquidate it, it’s worth less,” Land said.

Real estate moguls and others can use family limited partnerships to transfer interests in assets on to their children. A lowered face value of these interests is achieved through what are called “valuation discounts,” or techniques that allow the heirs to claim that pieces of the estate are not worth as much as they look like. Common examples include claiming that minority interests are not controlling interests and that this limitation inherently makes them worth less. Another discount stems from a lack of marketability for such an interest that can not be easily converted to cash.

However, family limited partnerships, which Renn described as “middle-class millionaire” maneuvers, are not necessary for many real estate operators, he said, because the LLCs through which they own properties are often organized such that they qualify for valuation discounts anyway.

Estate planning CPA Kim Dula, of the accounting firm Friedman LLP, said these kinds of valuation discounts usually add up to around 30 percent that can be taken off the taxable value of her clients’ estates — a huge difference for any estate.

But as with 1031 exchanges, these write-offs are now under a well-focused microscope in Washington. This year, the IRS proposed regulations that could severely limit the extent to which people can apply some valuation discounts to their estates. “The stakes are very, very high,” Dula said.

Land, who chairs the tax section of the New York State bar, said that people were overstating the planned reforms, but he acknowledged that the IRS is “certainly limiting some of the techniques in a major way.”

“You hear people that say the sky is falling down,” he added. Land is currently working on a report looking at whether the change constitutes a legitimate exercise of IRS authority. “This has been a staple of estate planning for decades. So there’s a lot at stake,” he said.