Chinese developer XIN Development made headlines last year when it landed a $165 million loan from Fortress Investment Group to build its South Williamsburg condominium, the Oosten. Now, the developer is looking for another $50 million via the much-ballyhooed EB-5 program.

Chinese developer XIN Development made headlines last year when it landed a $165 million loan from Fortress Investment Group to build its South Williamsburg condominium, the Oosten. Now, the developer is looking for another $50 million via the much-ballyhooed EB-5 program.

The immediate obstacle? Lining up 100 individuals who want to help fund the project.

Under the EB-5 program, foreign investors are granted a green card in exchange for a $500,000 investment in a U.S.-based venture that creates at least 10 jobs. But despite enormous popularity among investors and the real estate developers tapping into the cash, the program is a lengthy, labor-intensive and complex process, even in best-case scenarios. And the delays are getting worse.

“There really are hoops to jump through because it is a government program,” said Julia Park, managing director of the Manhattan-based Advantage America New York Regional Center, which acts as an intermediary between developers and investors.

The program is also battling a multi-layered public perception problem, with critics saying it allows wealthy foreigners to buy their way into the country and that it breeds fraud.

Despite the program’s shortcomings, demand has been surging over the past few years, particularly among Chinese investors. But that surge has further bogged down U.S. immigration officials, who are processing thousands more visa petitions than they used to.

The processing time for I-526 petitions — the first hurdle in the long process of obtaining a green card through EB-5 — is currently 14 months, up from roughly six months in 2011. And the delays are set to grow: On May 1, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the federal agency that oversees the program, imposed a Chinese “retrogression,” or wait list, for Chinese investors seeking EB-5 visas, meaning that anyone who applies now automatically takes a spot at the end of the line.

The wait list was put in place because the EB-5 program dictates that no more than 7 percent of visas can be allocated to investors from a single country. Until now, the program was underutilized; if investors from other countries didn’t use their alloted visas, the visas were offered to Chinese investors.

“At this point, the U.S. government is not processing any visas for people who haven’t initiated the process two years ago,” said Heidi Learner, chief economist at Savills Studley’s New York office, who published a white paper in March on EB-5’s impact on real estate.

Even if the backlog doesn’t depress demand — and many say it won’t, because investors’ top priority is obtaining a green card — the extra wait will be passed on to developers. And there’s a good chance some will balk at longer loan terms. “It reduces the overall universe of eligible projects,” said Justin Gardinier, a managing director at Greystone, who is establishing a new EB-5 platform for the Manhattan-based financial services firm.

Controversial start

From its inception, EB-5 generated backlash.

A 2013 routine audit by the Department of Homeland Security’s office of the Inspector General concluded that the U.S. government was “unable to demonstrate” the economic benefits of EB-5 investment.

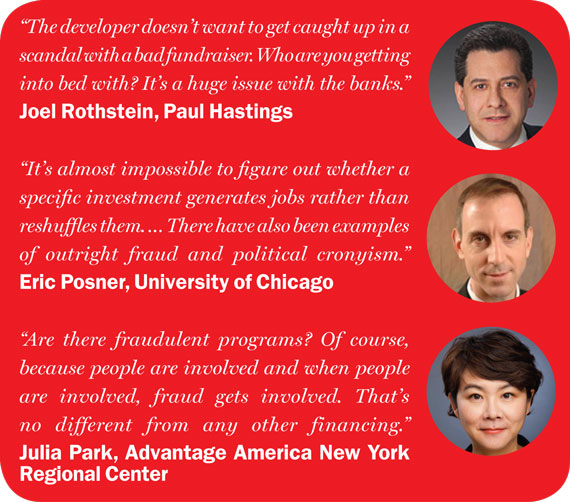

As recently as last month, University of Chicago Law School professor Eric Posner lambasted the program in an article published by Slate. Voicing the views of many critics, Posner said of EB-5: “It’s the worst combination of bad economics, political cronyism and unfairness.”

One of the biggest complaints about EB-5 is that it offers wealthy foreigners the chance to buy U.S. citizenship, but Posner also argues that the cost of entry is far too low.

“Among other things, it’s almost impossible to figure out whether a specific investment generates jobs rather than reshuffles them from one place to another,” he wrote. “There have also been examples of outright fraud and political cronyism.”

Critics say the program can be dodgy, citing some less-than-honest promoters who used the program to defraud investors.

Simon Henry, a co-founder of the Chinese property website Juwai.com, which is headquartered in Shanghai, said EB-5 investment had “quite a bad reputation” in China until about a year ago. Early on, the quality of projects and caliber of developers seeking EB-5 funding was lacking, he said. “A lot of Chinese got burned pretty badly,” he said. While that has changed, EB-5’s cottage industry has retained dubious elements.

Joel Rothstein, an EB-5 attorney at the law firm Paul Hastings who splits his time between Los Angeles and Beijing, said he’s seen countless EB-5 events and presentations in hotel lobbies in China.

“There are all these agents and promoters out there earning fees to rope in investors and that part has a little bit of sleaze to it,” he said. While those agents are generally not affiliated with established New York City developers, those developers often have to deal with the fallout of overall negative perceptions of the program.

On the domestic side, regional centers funnel deals to developers — for a fee. There are currently more than 640 regional centers throughout the U.S., including 62 in New York. In addition, nationwide there are another 340 applications pending.

On the domestic side, regional centers funnel deals to developers — for a fee. There are currently more than 640 regional centers throughout the U.S., including 62 in New York. In addition, nationwide there are another 340 applications pending.

And yet, there are only a few dozen regional centers a developer would want to do business with, said Rothstein.

“The developer doesn’t want to get caught up in a scandal with a bad fundraiser,” he said. “Who are you getting into bed with? It’s a huge issue with the banks. EB-5 is the wild west of finance,” he said.

Rothstein added that banks still don’t like to participate in deals with EB-5 money.

“They do deals notwithstanding EB-5, not because of it,” he said.

In 2014, a scandal in Chicago fueled critics of the program after authorities charged EB-5 promoter Anshoo Sethi with fraudulently raising $160 million from investors. According to the indictment, Sethi provided phony documentation to investors that suggested the project had backing from the U.S. government and certain major developers. He also allegedly spent most of the $11 million in fees he collected from hundreds of investors. Ultimately, Sethi settled with the SEC and was fined several million dollars.

Most recently, the EB-5 program came under fire amid allegations that the former director of USCIS influenced immigrants’ petitions at the behest of influential Democrats.

A March report by Homeland Security concluded that former Director Alejandro Mayorkas accelerated the approval of EB-5 applications as a favor to Anthony Rodham, brother of presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton and chief of global EB-5 investor relations and government affairs for the Philadelphia-based Global City Regional Center, as well as former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe.

Park, of the Advantage America Regional Center, dismissed the notion that EB-5 is saddled by widespread fraud. Instead, she said high-profile incidents have become politicized and have been seized on by critics of the program.

“Is there fraud? Yes. Are there fraudulent programs? Of course, because people are involved and when people are involved, fraud gets involved,” she said. “That’s no different from any other financing. I don’t think EB-5 is special in that way.”

Government crackdowns

Ayush Kapahi, a principal at HKS Capital Partners, said EB-5 is compelling because the cost of capital is so low, but he said it’s a long road.

“Look, I think the nicest way to put it is, if you have the patience, you could pursue EB-5 capital for your project and pay significantly less,” he said. But the process “inevitably leaves all fundamentals of business and real estate aside because it has to go through the government.”

Allegations of fraud have spurred increased regulatory oversight, both in China and the U.S. In 2011, the Chinese government imposed regulations on marketers of EB-5 projects.

“The Chinese are doing a little more due diligence,” said attorney Mona Shah, principal at Mona Shah & Associates in New York, speaking at The Real Deal’s New Development Showcase and Forum last month. “They will not rely on the American counterpart going across … they want to come over here and visit [the project] themselves.”

The Securities and Exchange Commission, too, is cracking down on EB-5, in the wake of both the indictment in Chicago and the latest Inspector General’s report.

Kate Kalmykov, an EB-5 attorney at Greenberg Traurig, said the beefed-up SEC oversight, including closer examinations of the broker-dealers who source investors and the soundness of regional centers, reflects the evolution of EB-5 as a market.

“It was in its infancy until 2009, 2010,” she said. “As it’s grown and developed, many billions have been raised. There has to be more compliance.”

Currently, regional centers are required to file annual compliance reports. This past fall, Kalmykov said the immigration agency indicated it would begin conducting site visits to see how investor funds were being used. “They haven’t done that yet, to my knowledge,” she said.

Of course USCIS can shut down a regional center if it doesn’t file the right forms, or if it fails to “promote economic growth as required,” according to the agency’s website. As of May 7, it terminated 29 regional centers, including the Buffalo Regional Center, the only terminated center in New York.

But it’s notoriously difficult to pin down the efficacy of a regional center.

“USCIS is not transparent, and generally makes very little information or data available for public release,” wrote Jeanne Calderon, a professor at NYU, and attorney Gary Friedland, in their recent paper, “A Roadmap to the Use of EB-5 Capital: An Alternative Financing Tool for Commercial Real Estate Projects.”

Further, there are “few requirements or standards” placed upon regional centers. And those centers and owners, the report said, are not required to possess any special qualification, education or experience.

“Many Regional Centers,” the paper states, “have not sponsored even a single project resulting in a successful EB-5 capital raise.”