On Oct. 3, 2008, Daniel Herzberg, a British expatriate in Spain, called his bank, the Icelandic Landsbanki, to ask if his money was safe. He had read reports about financial difficulties, but got an encouraging reply and told his wife “everything will be fine.”

On Oct. 3, 2008, Daniel Herzberg, a British expatriate in Spain, called his bank, the Icelandic Landsbanki, to ask if his money was safe. He had read reports about financial difficulties, but got an encouraging reply and told his wife “everything will be fine.”

Four days later, his account was frozen and the bank was nationalized.

Herzberg’s fate, reported in the Wall Street Journal at the time, was not unusual. When the U.S. housing bubble burst in 2008, it exposed a complicated web of financial stakes that few were aware of.

Banks in Iceland, Germany and elsewhere — not to mention U.S. institutions such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers — suddenly faced default as a result of their investments in U.S. mortgage-backed securities. Many of the individual depositors who got burned were fanned out across Europe. And the European economy is still reeling from that domino effect.

In the U.S., things are in better shape.

The U.S. housing market is steadily (if slowly) recovering, while New York real estate is breaking one record after another. And once again, capital from all corners of the world is flowing into the Big Apple.

But while New York real estate is widely regarded as safe, ballooning prices have some observers warning of the next crash. And those who are getting in now might have more to worry about than earlier investors.

“You expect that the people that enter [the market] late are usually the ones that have the looser lending standards,” said Mark Scott, founder and principal of the New Jersey-based capital markets firm Commercial Mortgage Capital. “Those that are late to the party usually [don’t do] so well.”

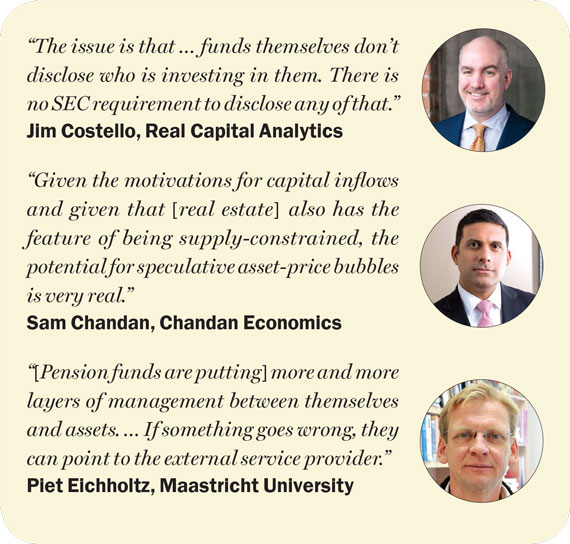

Sam Chandan, head of Chandan Economics and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, put it this way: “Given the motivations for capital inflows and given that [real estate] also has the feature of being supply-constrained, the potential for speculative asset-price bubbles is very real.”

Like most other observers, Chandan dismissed the suggestion that New York’s real estate market as a whole is in a bubble. But he expressed concerned about certain subsectors, most notably luxury condos and office buildings.

In addition, the devaluation of the Chinese currency last month along with the global stock market gyrations that followed, have unnerved investors in general and added another level of caution.

This month, against that backdrop, The Real Deal looked at some of the major stakeholders in New York real estate, those whose financial fates are tied to the market here. The question we set out to answer: Who will be left holding the bag this time, if New York’s real estate market tanks?

What we found is that in the six years since the Great Recession, institutions have not divested from the New York market, but have simply been making more indirect investments.

And untangling the global web hasn’t gotten easier since 2008. Despite the traumatic after-effects of the last crash, there is still no reliable data on where much of the money invested in New York real estate truly comes from. Firms like SL Green Realty and RXR Realty may top the rankings of biggest direct investors, but determining where those firms get their money is trickier.

From left: 140 Broadway in the Financial District and 610 Lexington Avenue

Available data on the types of investors in New York real estate merely scratch the surface.

For example, if the Blackstone Group (see related story on page 70) buys a building, most reports will count that as “domestic investment.” But Blackstone doesn’t actually pay for its properties out of its own wallet — and won’t suffer any immediate losses if the values on those properties plummet. The true stakeholders — the ones who would get hit if values fall — are the limited partners in its funds.

The same principle applies to real estate investment trusts or REITs, which have shareholders from all over the world, and to private developers, who lately have been financing projects through private funds or foreign banks.

And even if a domestic lender finances a deal, it may well securitize that loan and sell it off to investors across the globe.

“The issue is that [foreign investors and institutions] all invest in funds, but the funds themselves don’t disclose who is investing in them,” said Jim Costello, senior vice president at research firm Real Capital Analytics. “There is no SEC requirement to disclose any of that.”

While it’s impossible to know where all the money currently invested in New York real estate originated, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to paint a relatively clear picture.

While some major investors, such as U.S. pension funds and insurance companies, are familiar faces, others are novel. In recent years, the influx of Chinese investors and sovereign wealth funds has produced millions of new stakeholders in the New York market. This means that the number of people with a financial interest in New York is arguably more diverse than ever before.

If the market were to crash, the after-effects would undoubtedly reverberate across the globe. Below is a look at some of the players who have serious cash riding on the New York market.

U.S. and Canadian institutional investors: The indirect route

It’s no news flash that North American institutions got burned during the financial crisis (think mega-insurer AIG and the California savings association IndyMac).

So it would stand to reason that institutional investors — the catchall term for pension funds, banks and insurance companies — would be more cautious when investing in real estate this time around. And on first blush, that would appear to be the case.

Investments from institutional players pale in comparison when stacked up against private companies, such as, say, RXR or David Werner Real Estate. All told, private firms invested a combined $16.31 billion in New York real estate last year, according to RCA, versus institutional investors and private equity real estate funds’ $9.66 billion.

But while institutional investors may not be making as many primary investments in New York as in the past — they invested $23.57 billion in 2007— they invest heavily in other players who are buying big.

For example, institutional investors provide about 76 percent of the capital in Blackstone’s funds, according to a company spokesperson.

And the investor daisy chain extends even further because institutions don’t typically invest their own money. Instead, they serve as conduits for a large and diverse group of savers. And that means if the market sours in New York, those savers are the ones who will lose their shirts.

For example, both public and corporate pension funds, which are responsible for the retirement nest eggs of millions of people, are major investors in private real estate funds.

As of late 2014, California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, had invested more than $16 billion in U.S. real estate funds out of its roughly $295 billion in assets under management. Those investments were made through Savanna, headed by Chris Schlank and Nicholas Bienstock; Starwood, headed by Barry Sternlicht; CIM and other major real estate funds. MetLife, Prudential, AIG and other life insurance companies that act as investment vehicles for ordinary investors are also heavily invested in New York.

Institutional players are also the most dominant shareholders of the big New York–focused REITs.

For example, the mutual-fund manager Vanguard Group — which invests money on behalf of both ordinary investors and institutions — is the largest shareholder of Boston Properties, SL Green and Vornado Realty Trust, according to the investment research firm Morningstar.

That’s particularly noteworthy given that REITs have been on a New York buying spree lately, investing $6.29 billion last year, only slightly below their 2007 peak of $7.83 billion.

Piet Eichholtz, an economist at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, said pension funds, for one, are putting “more and more layers of management between themselves and assets.”

Interestingly, institutional players from Canada have taken a different approach than their U.S. counterparts. Rather than merely funneling money through REITs, private equity funds and other vehicles, they’re buying up property themselves.

The two biggest pension fund buyers of New York properties over the past five years are La Caisse de Depot et Placement du Quebec, which manages a nearly $200 billion pension plan that all workers in Québec are vested in, and the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, which manages pensions for public employees in Ontario.

As TRD reported in June, La Caisse, through its subsidiary Ivanhoe Cambridge, has been the most active direct pension fund buyer of New York real estate over the past five years, scooping up trophy towers like 3 Bryant Park. The firm has invested $3.8 billion directly in New York real estate over the past five years, according to RCA. OMERS, meanwhile, dished out $2.67 billion over the same period through its real estate arm, Oxford Properties Group.

The Chinese: Three waves and counting

The Chinese government has long capped interest rates on bank deposits, prompting many residents with wealth to look to real estate as a first investment options.

The aptly named David Dollar, an economist at the Brookings Institution and former U.S. Treasury emissary to Beijing, estimates that 20 percent of apartments in China are vacant. Many of them were bought as a store of value. In other words, buying an apartment in China is a lot like putting money in a checking account here.

Unsurprisingly, many Chinese looking to bring money overseas prefer buying an apartment in New York over, say, U.S. bonds. There are no conclusive statistics on how many Chinese nationals have bought in New York, but the consensus among brokers is that they’ve become the most dominant group among foreign buyers in recent years.

However, last month’s devaluation of the Chinese renminbi has added a new layer of uncertainty about Chinese investment in New York.

Some argue that by making New York real estate more expensive, the devaluation could keep some Chinese buyers out (see related story on page 90). But the more prevailing view is that the prospect of further devaluation, along with growing concerns over the Chinese economy, could encourage Chinese investors, who are already heavily invested in the New York, to double down here and invest even more.

And the above-mentioned investors are only the tip of an iceberg that includes Chinese development firms, Chinese banks and Chinese insurers.

Chinese development firms are, of course, making inroads in the New York market these days.

China Vanke, which is headed by Wang Shi, is partnering with developer Aby Rosen at 610 Lexington Avenue on a 61-story condo tower. Greenland Holding Group spent $200 million to buy a 70 percent stake in Brooklyn’s Atlantic Yards project, which was promptly renamed Pacific Park. XIN Development, a subsidiary of Xinyuan Real Estate, is building the 216-unit Oosten condo in Williamsburg. And they are just a few of the many Chinese developers in the city.

“This wave first started at the grassroots level and then the developers started to listen to their customers,” said Omer Ozden, a partner in the Chinese private equity fund Beijing Capital and an advisor to Xinyuan.

“There was so much demand [from Chinese apartment buyers], so the developers started to come,” he added.

From left: 7 Bryant Park, 3 Bryant Park and the MoMa Tower at 53 West 53rd Street

But while the first wave gave a large number of wealthy and middle-class Chinese a financial stake in New York, funding for the second wave is more concentrated.

Chinese developers generally invest their own equity in New York real estate, according to Ozden and others. This means no Chinese savers are on the hook for their deals. In fact, non-Chinese investors probably have much more of a stake — and more to lose if things sputter here.

Chinese developers have raised more than $66 billion in dollar-denominated offshore bonds, according to research firm Dealogic, which tracks the investment banking industry.

Greenland issued $2.7 billion in dollar bonds in 2014. Soho China, a stakeholder in the GM building, issued $1 billion in 2012. And China Vanke, which is China’s largest publicly traded developer, has issued $1 billion to-date.

Selling those bonds is attractive for Chinese developers because they are cheaper then Renminbi-based (or onshore) bonds.

But they are risky for foreign investors, because when it comes to recouping money after a default they stand further back in line. The recent default of Chinese developer Kaisa has made this painfully clear. Kaisa’s major foreign bondholders included mega asset manager BlackRock, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Fidelity Investment, and ING Investment Management.

But dollar-based bond sales by Chinese developers have reportedly slowed since Kaisa’s default.

Meanwhile, Xinyuan is also listed on the New York Stock Exchange, meaning U.S. shareholders are also sharing in its profits — and risks.

The third wave of Chinese investment, which is just crashing on New York’s shores, is made up of Chinese institutions.

In terms of funding, this new wave is somewhere between the apartment-buying model and the development-firm model.

When institutions buy buildings here, they typically do so with their own equity, according to Ozden. This means a large number of Chinese depositors each have a small share of their savings tied up in New York real estate. These depositors would only suffer from hypothetical losses if those losses were large enough to threaten the overall health of one of the large Chinese banks, such as the Bank of China, which is unlikely given the size of the bank. This is a major distinction from private banking, where wealthy individuals invest directly and carry all the risk.

Buying buildings, of course, offers potentially higher returns than, say, writing loans, but it also comes with added risk. In the event of a sudden drop in value, equity investors typically absorb the lion’s share of the losses.

The Bank of China, for example, purchased 7 Bryant Park last year for $600 million. In a case like that, the bank is directly on the hook should the market turn.

But the Bank of China has also engaged in more traditional lending, for which its depositors are likely also on the hook. For example, the bank is financing Vornado’s condo tower 220 Central Park South with loans totaling more than $1 billion.

Ozden expects that the fourth wave of Chinese investment will consist of a wider range of institutions and funds, including smaller ones. If and when that wave hits, it will bring more Chinese investors.

The Europeans: New times, new players

The influx of Chinese money has kicked Europeans from the foreign-investment throne. Once the most active foreign buyers in Manhattan, they suffered badly when the bubble burst in 2008.

While European money has since returned, it is coming from decidedly different sources. And that, of course, means that a different set of players will suffer this time around if the market declines.

Prior to 2008, banks from countries across Europe invested in U.S. real estate through direct loans and by buying mortgage-backed securities. That led to several high-profile bankruptcies such as that of Iceland’s Kaupthing Bank and Britain’s Northern Rock and helped usher in the European debt crisis. The after-effects of this financial earthquake continue to be felt today.

Today, European investment in New York real estate is coming from a much smaller number of core countries, said Borja Sierra, the head of U.S. capital markets for commercial firm Savills Studley. Particularly active are investors from Norway and Germany.

Today, European investment in New York real estate is coming from a much smaller number of core countries, said Borja Sierra, the head of U.S. capital markets for commercial firm Savills Studley. Particularly active are investors from Norway and Germany.

Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, Norges Bank Investment Management, has spent $2.61 billion on five New York properties since 2012, according to RCA. That makes Norway, a country with a population of only 5.1 million people, the third-largest investor here, behind Canada

and China.

During the same period, German investors directly bought 13 New York properties for a total of $1.58 billion.

What differentiates today’s investment by European firms from their Chinese counterparts is the large number of stakeholders involved.

While many Chinese firms simply invest their own money, European firms spend the money of thousands — or even millions — of individual investors.

The Norges sovereign wealth fund — which is headed by Yngve Slyngstad — is a primary source of funding for Norway’s pension system, which all of the country’s residents are eligible for when they turn 67. That means that if the market turns, it could impact millions of Norwegian pension holders.

Meanwhile, some of the most active German buyers have a myriad of small retail investors.

Jens Breckwoldt, a 27-year-old college student in Germany and a friend of this reporter, briefly became one of them in 2011, when he invested $100 in a fund managed by Union Investment, a Hamburg-based fund manager, that holds U.S. real estate, including the office building 140 Broadway. He also invested a total of $900 in nine other funds, as a way of diversifying.

This type of small-scale investment is common in Germany, and much of this money makes its way to New York.

Union invests the money of thousands of retail investors like Breckwoldt from affiliated bank branches throughout Germany.

Funds like Union are generally more flexible and liquid than private equity funds and offer the chance to invest smaller sums. In exchange, their returns are lower. “We generally need cap rates of 3.5 to 4 percent,” said Thomas Gnieser, the firm’s head of investment management in the Americas. He added the firm sees New York real estate as particularly attractive. “New York has high liquidity, high rent growth, and offers the opportunity to land great tenants.”

The true volume of European institutions’ investment in New York real estate is larger than news reports suggest, explained Gnieser. “Many invest covertly through other asset managers” such as LaSalle Investment Management or Blackstone, he explained. This offers an opportunity to tap into New York’s real estate market without having to build up a local presence.

Another German fund, Deka Immobilien, which last October bought two retail condos at 522 Fifth Avenue from Morgan Stanley for $170 million in partnership with Ashkenazy Acquisition, also pools money from thousands of German retail investors.

Then there’s the Munich-based fund manager GLL Real Estate Partners, which counts pension funds and insurance companies as its main investors.

Last summer, the company bought two retail condos near Times Square for a total of around $190 million, according to news reports.

“We have become far more active in New York,” said Christian Goebel, who oversees GLL’s East Coast activities. “You can generally say that there is a lot more demand from German investors for U.S. real estate today — especially for New York City.” These funds have no doubt looked closely at how big pension funds got hit the last time the market crashed. Canadian pension funds, for example, averaged losses of 18.5 percent in 2008, according to Canadian newspaper the Globe and Mail.

While GLL and the others might not be fearful of losing their shirts, it seems investors from Southern Europe — who generously (perhaps too generously) poured money into the New York market during the last boom — are. They have mostly disappeared from the Big Apple.

While GLL and the others might not be fearful of losing their shirts, it seems investors from Southern Europe — who generously (perhaps too generously) poured money into the New York market during the last boom — are. They have mostly disappeared from the Big Apple.

“Italian, Spanish and French firms now invest mostly in their own domestic markets,” said Savills Studley’s Sierra, who spent years working in continental Europe. “They are saying: why travel when my backyard is full of opportunity?”

Asia and the Middle East: The giant funds

Non-Chinese Asian institutional investors also have a lot riding on New York’s market. And if these investors get burned, their depositors could ultimately take some of the financial hit.

Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, GIC Private Limited, bought Blackstone’s portfolio of U.S. industrial properties for $8 billion earlier this year. The fund counts the country’s Prime Minister, Lee Hsien Loong, as its chairman.

In New York, meanwhile, Singapore’s United Overseas Bank has been an active construction lender. Last year, the bank financed Hines’ MoMA tower at 53 West 53rd Street with an $860 million loan. And it brought on two more banks from Singapore and one from Malaysia in a syndicate, meaning their depositors are now also backing the project — and sharing the risk.

Among Japanese investors, developer Mitsui Fudosan’s New York deals have been widely publicized. Other Japanese institutions have invested more quietly. For example, the investment bank Daiwa Securities Group is SL Green’s fourth-largest shareholder, according to Morningstar. This means Japanese investors are financially exposed if SL Green’s share price falls.

Most of the Middle Eastern money entering New York real estate comes in the form of sovereign wealth funds. Funds like the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and the Kuwait Finance House have bought Manhattan properties in recent years. As a result, the number of ultimate stakeholders is massive.

On a smaller scale, high-net-worth individuals are also making their presence felt. For example, Garrett Thelander, executive managing director at Cushman & Wakefield, told TRD that he recently worked on a $30 million construction loan for a wealthy Middle Eastern family that is developing a 12-unit condo building in Chelsea — in part to house its own family members.

Investors from India, the world’s second-most populous country, are still largely absent. But even that is starting to change (see related story on page 74). A larger influx of Indian investors would be the latest step in the globalization of New York’s real estate market.