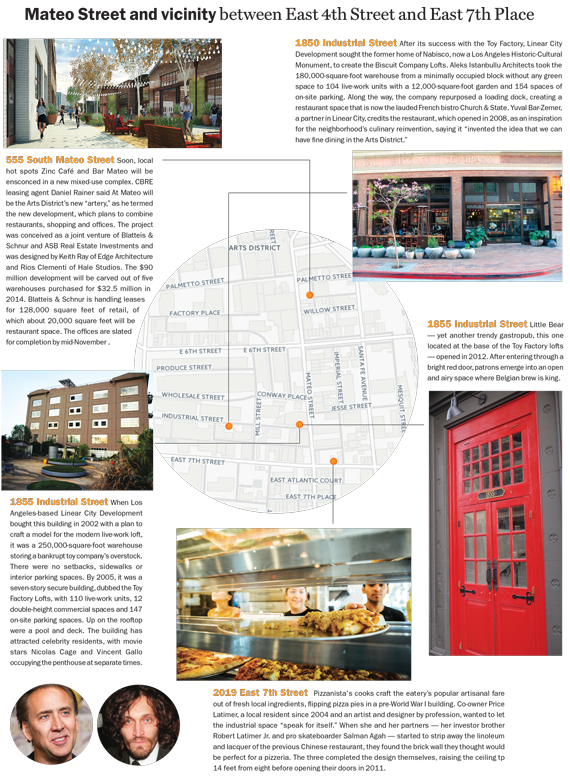

New crops of highly visible developments are seemingly sprouting up on every corner of the Los Angeles Arts District, a former warehouse neighborhood on the eastern edge of Downtown. Museums, cafés, gastropubs, crafts shops, lofts and creative workspaces are all opening up at a lively clip.

The district’s artistic revival could be dated to 2001, when the Southern California Institute of Architecture, known as SCI-Arc, moved its campus to an old rail freight depot here. Then, in an extension of the old live-work lofts of the artists who first colonized the neighborhood, developers started building creative workspaces in former warehouses of American industrial icons such as the National Biscuit Company, now known as Nabisco. The trend continues with the redevelopment of former Ford Motor and Maxwell House Coffee spaces.

All of this activity has been boosting asking rents for restaurants and shops looking to move to the neighborhood. “I’d say that there has been a 35 percent increase in retail rents in the last 18 months,” John Hillman, a 17-year veteran of CBRE, said in August.

Artistic revival

This post-industrial hub still has the factory buildings that characterized the neighborhood in the 1920s, when an industrial boom kept it busy. After manufacturing shifts and global trade required more vertical clearance to stack high-volume shipments, the Arts District’s four- and five-story square blocks of symmetrical floors became obsolete, and the sector was pushed out to areas like the aptly named Commerce, about six miles southeast.

The upper floors of the buildings, left empty for years, were eventually populated, in part, by a migration of New York artists needing cheap and voluminous space. The community of bohemian crafters living in their work studios transformed the mini-factory town into the Arts District. “You couldn’t even lease these places at 10 cents (per square foot). People were living there when they shouldn’t,” Hillman said.

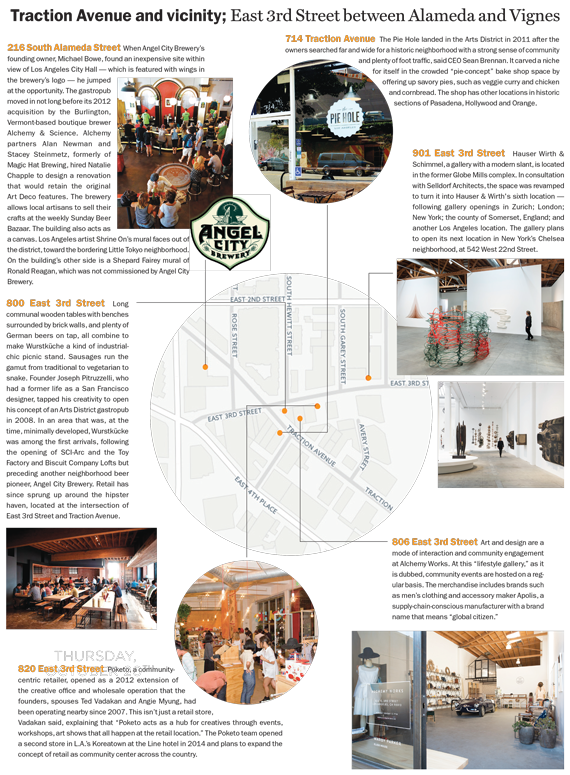

A mural on district anchor Angel City Brewery by Shepard Fairey (inset).

In 1981, the Artists in Residence Ordinance allowed artists to legally live in the industrially zoned units. Then, in 1999, another ordinance allowed a separate set of building standards that relaxed safety-retrofitting guidelines for buildings constructed before 1974, an attempt to preserve space that would otherwise be destroyed because of the costs of retrofitting. The city’s grudging tolerance of the artists’ illegal dwellings, combined with easier redesign for developers, gave rise to the modern urban real estate phenomenon of live-work lofts.

Then developers caught on to an investor’s dream: inexpensive, easily repurposed open space in buildings with good bones.

Two landmark projects from Linear City Development — the Toy Factory Lofts in 2005 and the Biscuit Company Lofts in 2007 — set the stage for converting hollow, neglected factories into mixed-used models of functional high density.

Lately, the emphasis has turned toward offices for media and entertainment companies. Shorenstein Properties is repurposing an old Ford Motor factory into a 255,000-square-foot gleaming corporate campus. New offices are also in the works at 405 Mateo Street, where developer Hudson Pacific Properties is preserving the old Maxwell House Coffee facility’s original wood-stamped concrete ceiling, weathered brick façade and walls, large floor plates and oversized windows.

Carl Muhlstein, regional director at JLL, said the neighborhood’s development success came as a surprise. “The early real estate players were local families,” he said. “All of a sudden the real estate became more valuable than whatever they were doing in that building.”

To a large extent, the district’s story is similar to those of other former industrial neighborhoods in other post-industrial cities — progressing from students and artists moving in as residents to funky retailers opening up shop, with an influx of office space as the final phase.

“It’s not different from Santa Monica’s creative areas, where downtown Santa Monica and Third Street Promenade hit it out of the park and the offices followed,” Muhlstein said.

This familiar pattern has some longtime denizens worried about the risk of spiking rents and fading neighborhood character. Across the river — in the adamantly anti-gentrification neighborhood Boyle Heights — the Arts District is regularly cited as a cautionary tale. The term “artwashing” is applied. Even longtime galleries have to defend their authenticity to an anxious community. An original Shepard Fairey mural on the exterior of the district anchor Angel City Brewery, warning of legislators available for purchase, shows the neighborhood’s spirit of art as subversion.

CBRE’s Hillman said that while chains like Umami Burger are coming in, and the recent changes are “just the tip of the iceberg,” the district’s artistic core will remain. “Even with institutional investment, the Arts District hasn’t lost that artistic spirit,” Hillman said. “You’re not going to see a Foot Locker. You’re not going to see a Starbucks.”