Gregg Singer is not, it turns out, a conspiracy theorist.

Singer had for years blamed his failure to redevelop a former East Village public school on corrupt city officials, a secretive billionaire and even the personal intervention of Mayor Bill de Blasio.

He filed lawsuits, hired lobbyists and told anyone who would listen, but neither judges nor the media believed his far-fetched story about a devious cabal denying him routine building permits. Meanwhile, the old P.S. 64 building fell into disrepair and his debt on it swelled to more than $100 million.

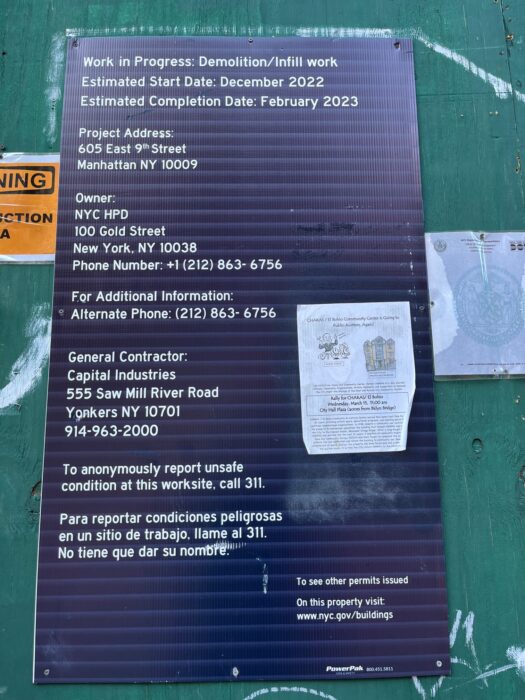

To stave off foreclosure, Singer put the five-story, 152,000-square-foot property at 605 East Ninth Street into bankruptcy. But after 24 years of futility, his chances of salvaging any of his investment, let alone realize his ambition to create a dormitory, seemed dashed.

Then he found the emails.

Public records requests he had filed yielded a treasure trove of messages backing up the claims that no one had taken seriously.

The billionaire, hedge funder Aaron Sosnick, had indeed made requests — amplified by campaign contributions — to city officials to deny the renovation. De Blasio had in turn intercepted the Department of Buildings’ decision to grant Singer’s permits.

The revelation was rare if not unique in the annals of New York City development. And the emails exposed surprising layers to the behind-the-scenes drama.

They showed de Blasio’s senior staff was aghast at the mayor’s plan to buy back and renovate the dilapidated school — a money pit mired in litigation and debt — and lease it to nonprofits, as local politicians and wealthy neighbors wanted. In one email, Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen called the idea “nuts.”

Developers’ projects are often delayed by bureaucracy or killed by politics. What was unusual in Singer’s case is that he was stymied for two decades despite not needing new zoning or elected officials’ sign-off. Getting building permits is supposed to be, and nearly always is, apolitical — a task for anonymous expeditors, not lobbyists and media consultants.

Discovering the emails was life-changing for Singer, who has been pursuing the white whale of P.S. 64 for four administrations and most of his adult life. He bought the building in 1998, when he was 36.

“Think of that — 25 years just to renovate an existing building for any legal use and the government says no,” said Singer.

Not only did the emails vindicate his claims and bestow long-sought credibility, but they give him leverage to extract a huge settlement from the city.

One attorney even used a term Singer hadn’t heard before: “half a brick.” As in, half a billion dollars. That is surely an exaggeration, but the emails have set Singer’s runaway losses on P.S. 64 in a whole new light: As they grow, so does the city’s potential liability.

Singer is suing for damages but also to finally start the project that has so consumed him. But the emails may have come too late to save it.

Madison Realty Capital, known for its relentless efforts to be paid back when borrowers default, is trying to foreclose on the property, and Singer owes more than 30 times what he paid for it. Madison declined to comment.

The Adams administration, for its part, is treating Singer much like de Blasio did. Although desperate for sites to shelter migrants and other homeless people, the city has not inquired about using P.S. 64. It is also dismissing the significance of the emails, which show the previous mayor’s office halting the project as requested by East Village politicians and a wealthy donor.

“Mr. Singer is trying yet again to introduce baseless and unsupported claims into this case,” said a spokesperson for the city Law Department, which has asked a judge to throw out Singer’s lawsuit.

Singer, now 61, is not deterred. He still envisions a dorm at 605 East Ninth Street but says he is open to municipal uses, including to shelter migrants or homeless New Yorkers.

“Ownership is agnostic as to the property’s use,” said his attorney, Ayall Schanzer.

Bad omen

Singer’s odyssey dates back to the Giuliani administration, which auctioned off the former school, known at the time as the Charas/El Bohio Community Center. That day, protesters released thousands of crickets in an effort to stop the sale, but Singer, then in his late 30s, won with a $3.15 million bid.

“Within seconds, people are screaming and jumping on their seats,” Singer recalled 20 years later in an interview with the New York Times.

A deed restriction imposed by the City Council before the sale limited the site’s use to a “community facility.” A dorm — a valuable recruiting tool for colleges — would qualify, but community activists wanted Charas to remain. Singer nonetheless evicted the nonprofit in 2001.

Singer, who is the fourth generation of a New York real estate family and had a background in commercial mortgages, sketched out a plan to convert the five-story building to 27 stories, then pared it back to 19.

But in 2006, activists persuaded the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate his building as historic, effectively freezing its height. The city also restricted what qualified as dormitories, a rule it used later to deny him permits.

In 2012, some 14 years after Singer bought P.S. 64, he lined up its first tenant, striking a deal with Cooper Union to lease the second and third floors. A year later, he inked a lease with the Joffrey Ballet School for the ground and first floors.

Singer argued that Joffrey complied with the dorm rule because it was a nonprofit with sleeping accommodations. But East Village City Council member Rosie Mendez cried foul, and in 2014, the Department of Buildings issued a stop work order. In March 2016, it revoked Singer’s permits, saying his plans did not comply with the site’s zoning or the building code.

Singer’s outside investors grew restless. They sued in 2015, claiming he was lining his pockets with management fees of $30,000 per month. Led by Los Angeles-based Onyx Asset Management, they sought to boot Singer from the project and sell the school. Singer called these allegations “meritless” and said the fees were allowed under the operating agreement. The case was settled in 2017.

Having lost Cooper Union and Joffrey Ballet, Singer found another tenant in Long Island-based Adelphi University, which planned to house international students at the property beginning in September 2018.

Landmarks approved Singer’s plans, but the Department of Buildings went quiet on him for eight months. Behind the scenes, though, it was anything but quiet.

“A big F-U”

The emails show a flurry of activity involving Sosnick, Mendez, the Department of Buildings, aides to de Blasio and Andrew Berman of the activist group Village Preservation.

Sosnick, who owned a penthouse in a condo next to the old school, campaigned furiously to keep Singer from getting building permits to create a dorm and tapped George Arzt — the well-connected former press secretary to Mayor Ed Koch — for public relations and lobbying, according to the emails.

“May I submit that it is urgent if not an emergency for you to reach out, in an informed manner as possible, with as much help to the Mayor’s office as possible as well as to Adelphi University to make the case that this written determination and a dormitory in old P.S. 64 are not appropriate,” Sosnick wrote to Mendez.

The billionaire, who did not respond to a request for comment, was right about the urgency: Singer was close to getting approval. On Aug. 23, 2016, the Department of Buildings’ Patrick Wehle wrote to de Blasio aide Yume Kitasei that the agency had reviewed the lease with Adelphi and that “we’re ok with it.”

“We will be lifting the stop work order and issuing the permit,” Whele informed the aide.

“Hold off,” Kitasei responded.

Kitasei emailed another de Blasio aide, Jon Paul Lupo, that granting the permits “is exactly what Mendez didn’t want.”

Lupo suggested that denying the permits could be a trade-off for a garbage-truck depot that the administration wanted to locate in the Council member’s district.

“This is the building we talked about the other day. Need this as part of negotiations with Mendez re sanitation garage,” Lupo explained. Granting permits for P.S. 64, he added, “would be a big F-U to the community folks and a potential giveaway to the owner.”

Singer, though still awaiting city approvals, was confident enough to borrow $44 million from Madison Realty Capital. The loan was costly, with an interest rate close to 11 percent, but gave him the capital to get the project off the ground. He just needed the permits.

That possibility made local politicians frantic. The Department of Buildings had issued a determination that a permit could be issued if Singer submitted evidence of a lease.

Mendez, then-Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, State Sen. Brad Hoylman and Assemblyman Brian Kavanagh formally asked the agency to rule that the Adelphi lease would not qualify P.S. 64 as a dormitory.

Meanwhile, Paul Wolf of Denham Wolf Real Estate Services, who had been emailing with Sosnick about Madison’s loan to Singer, extended a curious offer to the powerful City Planning Commission chairman, Carl Weisbrod. Wolf wrote in January 2017 that he represented a “charitable entity” that would pay “in excess of $50 million” for the property.

The offer actually came from Sosnick, according to Singer’s lawsuit and emails from the records search. Sosnick continued to email lobbyists about how East Village politicians could persuade the administration to stop the project.

“This seems to be in the administration’s hands….Do we know of anything the Mayor needs from them that they can threaten to withhold?” the hedge funder wrote in early 2017.

The project was still in limbo, but Singer had hired lawyer and former City Council member Ken Fisher and media-savvy lobbyist Richard Lipsky to do public relations and draw attention to his plight. That led Glen to email her fellow deputy mayor Anthony Shorris about the site.

“Personally, I think that having Adelphi in the building meets the requirements of the deed, but it is not my call,” she wrote.

On Aug. 22, 2017, the Department of Buildings determined that the Adelphi lease did not qualify P.S. 64 as a dorm because Adelphi was a trade school, not a university, although it was incorporated as a college in 1896 and has been a university since 1963. The agency also ruled that the agreement did not give the school sufficient control of the building. Singer’s deal was dead.

Less than two months later, the other shoe dropped: On Oct. 12, one day after Sosnick attended a de Blasio fundraiser in Brooklyn, the mayor appeared with Mendez at a town hall meeting and told the crowd he intended to “re-acquire” the property.

De Blasio’s own inner circle, likely unaware that Sosnick had just donated $1,000 to de Blasio’s re-election campaign, was shocked.

“Where did this come from?” wrote Shorris in one email. “This building could be worth over 100 million and there’s not much we could do with it. Who do we think encouraged him to say this?”

Glen responded, “Do you know how much money this is going to cost us??? This is nuts.”

“Reminds me we still have not figured out a credible use for this building yet,” Shorris wrote in another exchange. “Hard to imagine what we would do with it if we had to pay this guy [Singer] what he’d want, but eventually he or someone will have to write this off and move on.”

But Singer managed to hold on to the graffiti-covered property, even as his debt swelled and his lawsuits and permit applications went nowhere. In a November op-ed in Crain’s, he delivered a blistering account of the saga.

“The level of political obstruction against my effort to develop the property I own has been unprecedented,” he wrote. “I have spent millions of dollars fighting a dedicated group of activists, their sugar daddy [Sosnick] and the city of New York. Now the mayor — pandering to his political supporters — is publicly saying he wants to reacquire my property. Mr. Mayor, it is not for sale!”

The next year, 2018, Madison Realty filed to foreclose, saying its loan had matured without Singer paying it off. When Covid hit in 2020, Singer offered up the site as a triage center, but the de Blasio administration wasn’t interested. The pandemic did, however, delay foreclosure.

In early 2022, a state judge ruled that Madison could move ahead. Justice Melissa Crane wrote that Singer’s responses, including a 25-page document that lacked a table of contents, amounted to a “rambling litany of defenses.”

Read more

The bankruptcy filing bought Singer more time, during which his records request came back with the bounty of emails. He also moved his case against the city from state to federal court, where he hopes to have more luck.

But 18 months after de Blasio left office, the developer still does not have building permits. If approved for student dorms, he projects, the building would generate about $12.4 million in net income the first year and up to $16 million by year 10. (Crain’s reported that the Adelphi lease would have netted Singer students’ room charges plus $373,500 annually.)

Financial considerations aside, Singer said he is driven by the principle that owners must be able to use their property as the law allows.

“I am not the type of person to give up when I know what is just,” said Singer. “This is an ‘as of right’ project and what I am fighting for benefits the project and anyone wanting to build or renovate in New York.”

Last weekend, while visiting the old school building for a photo shoot, Singer struck up a conversation with a man and woman sitting on its steps.

James Doukas, 52, said he has lived in the area for a number of years, but ended up on the street after a tenant he was renting from was evicted. He said Niko once went to a homeless shelter, but was assaulted, so he stays by her.

Singer reached into his backpack and showed them the property’s marketing materials, which tout it as potential homeless housing.

Niko, 45, said she remembered the protests over the building and the name Gregg Singer.

“I’m Gregg Singer,” Singer interjected.

The would-be developer launched into his story about how backroom politics and a billionaire neighbor have stopped him from obtaining permits. Twenty-five years in, he is still looking for an audience.