Call it the Icarus Effect: Flying higher than anybody sends you crashing back to Earth. That rule seems to apply to Manhattan’s office rents, which are declining more sharply than those in other U.S. markets, though it’s probably due to a soaring multi-year run-up.

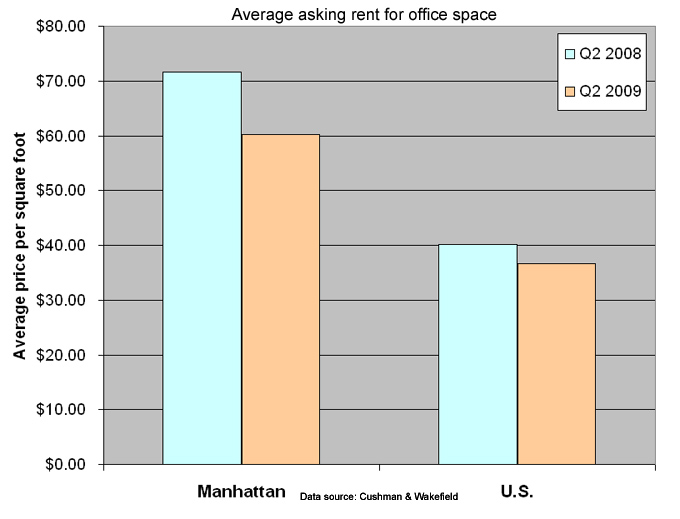

In the second quarter, average Manhattan asking rents were $60.23 per square foot, down from $71.59 a year ago, or an almost 16 percent plummet, according to Cushman & Wakefield, the commercial brokerage, which analyzed the three sub-markets that make up Manhattan’s central business district: Midtown, Midtown South and Downtown.

In contrast, the average price in the second quarter in all U.S. markets together, from Atlanta to Tucson, was $36.70 per square foot, down from $40.19, or a nearly 9 percent drop, the data shows.

“New York trails the rest of the country,” said John Gilbert, the COO of Rudin Management, one of the city’s larger office landlords, agreeing that New York is currently experiencing more of a brunt from the downturn than other national office markets. But he attributes it to a historical lag: “Different areas go through different cycles at different times.”

Indeed, while Manhattan’s fortunes may appear to be nearly twice as bad as the rest of the country, Manhattan’s steep tumble is better understood by looking at how high and fast rents climbed, landlords and brokers say.

Indeed, between the boom years of 2005 and 2008, Manhattan office rents shot up by 80 percent, to $72.95 per square foot from $40.48, while nationally they went up by just 54 percent over the same three-year period, to $40.37 from $26.23, the Cushman data indicates.

Wall Street, a core city industry, whose private equity firms and hedge funds mushroomed in size in lockstep with the surging stock market, was a key driver of this spike, brokers say. But another factor fed it: lack of supply.

First, the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 wiped out commercial space. Then, developers converted many of the Class B and C office buildings downtown into condos.

Simultaneously, almost no new office towers were being built, according to Ken McCarthy, a Cushman research director. In fact, just two were completed: 11 Times Square, from SJP Properties, and 510 Madison, from Macklowe Properties. This stands in stark contrast to the late-1980s boom, which culminated in a glut of space.

“It caused developers to be more cautious,” McCarthy said. “It’s why you have not seen a huge amount of new construction since then, and why much of what you’ve seen was pre-leased.”

Now, Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns are gone, and other companies are downsizing, prompting the office vacancy rate to spike — it was at 10.5 percent in the second quarter, versus 7.1 percent a year ago, Cushman found — which puts considerable downward pressure on prices.

And the city’s unemployment rate doesn’t bode well for the office market. On Friday, the state Department of Labor announced it was at 9.6 percent in July, surpassing the national average of 9.4 percent in July; that’s up from 5.4 percent in July 2008.

But brokers suggest the job losses aren’t as severe as those figures might indicate; better to consider the payroll-employment number — measuring those who work in the city, as opposed to those who simply live there. It shows just a 2.9 percent fall in employment since last July, said Jim Brown, a state labor analyst.

That there are still jobs here might explain the city’s suddenly busy sublease market, as now-shrunken banks rush to unload unused office space, brokers say.

“Companies that paused last winter are now coming back in the market. They have leases expiring, and they have to do something,” whether white-shoe law firms or technology startups, said McCarthy, adding that the space is already built out, which can reduce new tenants’ capital outlays.

The gap between leased and subleased space is quickly widening, from $5 at the market’s height to $23 this summer, McCarthy pointed out, which potentially puts many landlords at risk, particularly if it means their primary tenants can’t cover their obligations, even with subletters in place.

Steve Durels, director of leasing for SL Green Realty, which is the city’s largest commercial landlord, told Reuters last month that his buildings’ occupancy rate, which was at 96.2 percent in the second quarter, or 22.1 million leased square feet, will fall to 94 percent in 2010, or 21.6 million leased square feet. Durels declined to comment through a spokesperson.