With a rapidly aging pool of commercial towers, New York has fallen behind dozens of other international cities, which are adding state-of-the-art office space to their building stock at far faster rates than the Big Apple.

Just 2.6 million square feet of office space was under construction here as of the end of June, ranking Manhattan an abysmal 34th in a list of international cities producing new, modern commercial space, according to a review by Colliers International. That number only includes 1 World Trade Center, but if 4 World Trade Center, which is also under construction now, is factored in, the number jumps to 4.9 million square feet.

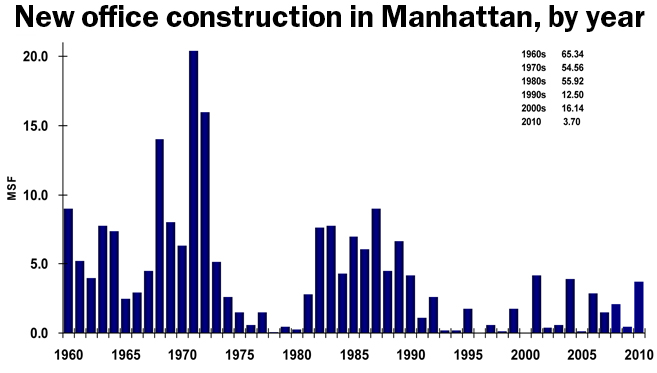

Still, according to Cassidy Turley, in 2009, just two office buildings were delivered in New York: One Bryant Park and 510 Madison. So far in 2010, 11 Times Square, the Goldman Sachs tower, 41 Cooper Square, and 400-404 First Avenue have all been finished, and 450 West 14th Street is expected to be completed by the end of the year. That means by year’s end, 3.73 million square feet of space will have been delivered in Manhattan.

Yet even with that combined with the more than 10 million square feet planned to come online over the next five to 10 years at the World Trade Center site, New York City is still lagging behind many of its international counterparts.

Overall, the construction of new office towers, like all construction, has been depressed in New York. That reality has some observers worried about whether New York will be able to compete globally to attract international corporate tenants.

The reasons for the lack of commercial construction are varied. For starters, the economic downturn has put a freeze on credit and the brakes on construction. In addition, while lower than they were during the boom, land and construction costs remain relatively high compared to a number of other cities — and political red tape and bureaucracy in the city are notoriously messy.

There are projects on the drawing board, but many of them don’t have shovels in the ground yet. For example, the Related Companies, which has delayed its development plans for the Hudson Yards on Manhattan’s Far West Side because of the downturn, is now beginning to consider some development projects there.

At The Real Deal’s annual forum last month, company president Jeff Blau said the firm won’t start new construction in New York for at least 18 months, but he said there has been a “tremendous amount of corporate interest,” and Related is working with several potential commercial tenants who would look to take more than 1 million square feet of space.

At present, though, both New York and London — which have been locked in a head-to-head struggle for the title of the world’s “financial capital” — must reckon with surging cities like Shanghai, Singapore, Moscow and S„o Paulo, among others. Those cities are leaving London and New York in the dust when it comes to adding new, state-of-the-art office supply. Technology may be making the world smaller, but these other emerging cities — hungry for their share of the global economic pie — are only getting bigger.

“I wouldn’t call it alarming yet, but it is of great concern to me. I think we live on a larger playing field than we used to,” said Vishaan Chakrabarti, the head of the Real Estate Development Program at Columbia University’s School of Architecture. “What I see is a leapfrogging taking place [by other cities] in terms of new buildings.”

Take Shanghai, which ranked at the top of Colliers’ list with 37 million square feet of office space being constructed right now — and what research manager Colin Bogar of Colliers calls a “never-ending stream of new construction over the coming years.”

In Shanghai’s Pudong District alone, the city will soon have the world’s second-tallest tower — the Shanghai Tower at 2,073 feet — which is part of a trifecta of new office buildings being built. (The two others are the 88-story Jin Mao Tower and the 101-story Shanghai World Financial Center.) All three structures are incorporating the newest in sustainability technology, like rainwater recycling systems for heating and cooling and built-in wind turbines to create on-site power. Colliers believes the market will “adequately absorb the new supply” with an office vacancy rate of around 10 to 15 percent, Bogar said.

For its part, Moscow (which ranked second in terms of building, with about 30 million square feet under construction) will have the City Palace Tower, a mixed-use development with 860,000 square feet of offices due for completion in summer 2011. Meanwhile, Dubai (ranked third, with 28 million square feet under construction) is currently developing the massive Business Bay complex, which by the end of this year will have 3.6 million square feet of additional space, 7 million by the end of 2011, and 11 million by the end of 2012, though that space will likely be hard to fill. Last month, Bloomberg News reported that the overall office vacancy rate in the emirate is 40 percent.

To be fair, unlike many of these other urban centers, Manhattan has already gone through several building booms over the past 80 years.

But New York’s existing pool of office space, while extremely large and enviable by most standards, poses its own set of problems. Almost 90 percent of the 450 million square feet of existing Manhattan office space was built before 1970, according to the Real Estate Board of New York. That means 40 years of environmental, technological and engineering advances were not factored into the construction of a huge portion of New York’s office buildings (with the exception of office retrofitting).

This comes at a time of heightened concerns about sustainability among multinational corporations. More and more Fortune 500 companies are imposing stricter criteria for the sustainability of their corporate headquarters, looking to boost their environmental bona fides and cut operating costs by occupying state-of-the-art, LEED-certified towers.

Last year, the Bloomberg Administration passed legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from existing government, commercial and residential buildings in New York. When the legislation passed, the mayor’s office predicted 85 percent of the existing buildings will be in use in 2030 — a clear indication that it expects much of the current stock of office towers will be retrofitted.

Margaret Castillo — president-elect of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects, and a leading proponent of retrofitting — said New York’s stock of Class A buildings are all designed well enough to be upgraded through a reexamination of their insulation, airflow, lighting, carbon dioxide monitoring and building controls. The problem, she said, is with Manhattan’s Class B buildings.

Others, like Columbia’s Chakrabarti, think building new towers might be more efficient.

“I do think that we have to consider a world further out where we ask what kind of zoning and tax policy do we need in place which would then make it more sensible to tear down a skyscraper and put up a new one,” he said. “We can’t stick our heads in the sand like ostriches.”

Source: Cushman & Wakefield