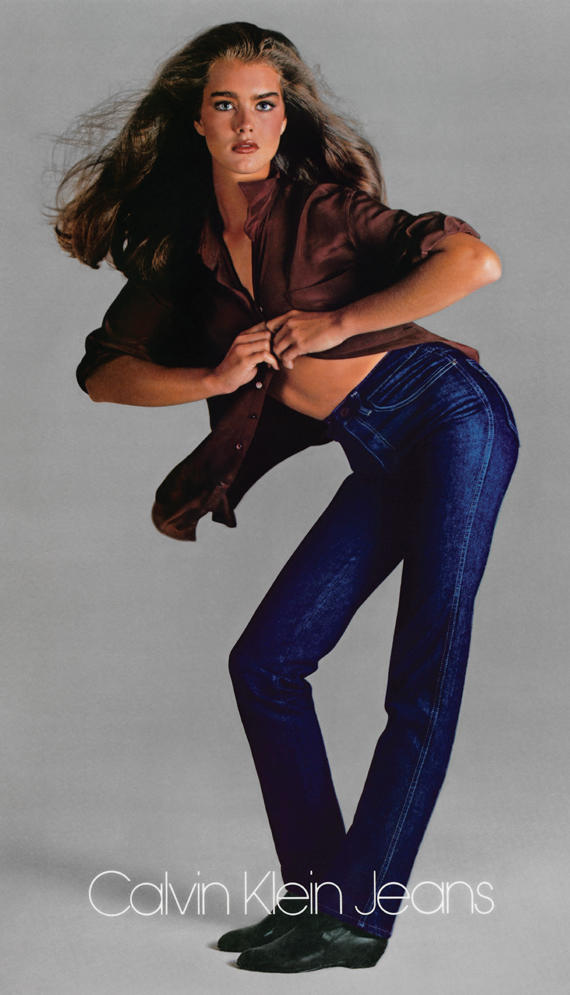

An artifact from another era, her skin-tight Calvin Klein jeans are now on display at the Fashion Institute of Technology. A pair was previously shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her oft-controversial childhood portraits have been exhibited in the Whitney, the Guggenheim and the Tate — where the photographs were removed after a warning from the London police. But Brooke Shields, 50, is far from being a museum piece.

Defying the mantle of victimhood thrust upon too many child stars, Shields has had a robust and surprisingly diverse five-decade-long career. She balanced steamy art house roles and squeaky-clean mainstream good-girl parts. In recent years, she branched out into comedy.

In her latest role, Shields plays a Manhattan-lawyer-turned-florist with a penchant for solving crimes in the “Flower Shop Mysteries,” premiering this month on the Hallmark Channel. “It is sort of like ‘Murder She Wrote,’ ” she says, during a recent interview with this reporter.

Perhaps it’s only fitting that Shields is playing a Manhattanite again. While she’s part of the broader celebrity firmament, New Yorkers have long embraced her as one of their own. Speaking with friends, family and colleagues in preparation for this interview, I was surprised by the range of memories she inspired, and how each claimed a specific connection to her.

A magazine publisher remembered his teenage crush on Shields after watching “Blue Lagoon.” My father, the same age as Shields, quoted her Calvin Klein commercial word for word when I called him after booking the interview. A friend in real estate asked me about her much-publicized feud with Tom Cruise over her use of antidepressants while struggling with postpartum depression, as discussed in her best-selling book “Down Came the Rain.” My tennis-playing roommate recalled her marriage to Andre Agassi in the late 1990s.

But none of this is the legacy Shields herself hopes for.

“There is always this very fine line between being flattered, and also realizing the arbitrary nature of it,” Shields says, referring to the fame she derived from her early career as a model. Her first modeling job was at 11 months old for Ivory soap, and by age three, she was a runway model. At nine, she had a controversial role as a child prostitute in the film, “Pretty Baby,” which won the Technical Grand Prize at the 1978 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Palme d’Or.

“I just happened to be at the right place at the right time, and I looked a certain way. There is nothing I did to look that way,” she says. “My parents had me, and all of a sudden there was this certain trajectory. What I hope is that I have registered with people by giving them honesty and entertainment.”

Shields says that her most satisfying moments are when she is able to reveal her own experiences and say “you aren’t alone” to those facing difficult-to-discuss issues like postpartum depression. Creatively, she is proudest of playing against type.

“My proudest times are in being able to make people laugh,” Shields says. Her sitcom “Suddenly Susan” ran from 1996 to 2000 and earned her a Golden Globe nomination. “I hope that I am remembered as not just an actress, but as a comedic actress as well.”

But comedy wasn’t an easy transition, Shields says, not because she didn’t have the knack, but because of her public perception as a pretty face.

“I had just never been given the chance [to do comedy],” she says. “I had been on 27 Bob Hope shows. I lived for comedy. Watching comedies, being in the plays at school and laughing with my mom: Those were the purest times. But that wasn’t my role. I was a model and I looked a certain way.”

To say that her early films, like “Pretty Baby,” “Endless Love” and “Blue Lagoon,” are not movies known for their comedy is an understatement.

“That was the path people wanted me to go on. In that era, you couldn’t be pretty and funny. They weren’t celebrating that in Hollywood. When “Friends” came along they really let me be crazy and funny. That was a revelation for other people. It was such a relief to me,” Shields says, referring to her 1996 appearance on the long-running sitcom. It was a breakthrough that earned her roles in hit comedies like NBC’s “Lipstick Jungle,” “That 70’s Show,” “Hannah Montana,” “Two And A Half Men” and “The Middle.” Last fall, Shields lent her voice to Adult Swim’s new dark and surreal animated series “Mr. Pickles.”

Still, Shields insists both in this interview and in her recent memoir, “There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me,” that she is in no way a victim of those early roles or her mother, Teri, who acted as her agent. On the contrary, she says that without her mother’s guidance and support that she could have suffered the anticlimactic fate of many other child stars.

Not only did her mother insist that she stay in school, but she refused call times during school hours. “That was unheard of,” Shields says. “It was an unprecedented way of handling talent. It gave [my mother] a horrible reputation, and she pissed

everybody off.”

Shields argues that spending her life in Manhattan, rather than Los Angeles, also helped her dodge pitfalls.

“I never left Manhattan, which I actually think is a really, really big piece. Because as crazy as people think this city is, the people who went out to California and were taking high school equivalency tests and just going into the entertainment industry and living that life, they had no safety net,” Shields says. “Whereas in New York, I do believe that there is [a safety net]. It’s not just that if you can make it here you can make it anywhere, but there is an intrinsic code of ethics here I believe.”

Shields grew up on the Upper East Side. Her father was an Italian-American aristocrat. Her paternal grandmother was princess Donna Marina Torlonia dei Principi di Civitella-Cesi. But after her parents divorced, she spent the majority of her time with her mother, who would expose her to Downtown New York’s bohemian side.

“My dad lived on the Upper East Side, and I was with my mom and working and eating Chinese and Indian food. I spanned both sides ever since I was a little kid,” she says. “You know in the 1980s, you didn’t go walking around the Meatpacking District — but I did with my mother. In the 1990s we’d do the Love Balls and Paris is Burning [ball]. I walked in the Love Ball for Paper Magazine [in drag] and we won.”

“Acting is like a blood infusion for me.”

As a child, Shields’ mother took her and a group of friends to see “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” in the East Village. “There were people in cages and stuff. It was hysterical. I was exposed at a really early age to the color and the vivacity of it all,” Shields says, adding that she and her husband, producer and screenwriter Chris Henchy, endeavor to do the same for their two daughters.

“There should be nothing that they are threatened by or afraid of just because it is different,” Shields says. “I think people learn to be afraid of things that they don’t understand, and so whether it is someone transitioning, or someone who is in the art world and is sort of outrageous, if you really indulge it and get into it, I think you gain appreciation. You don’t have to subscribe to it. You don’t even have to like the art. But you have to be able to be able to say, ‘Okay, that is this person’s point of view.’ I think New York is very good at giving all points of view.”

But despite her apparently glamorous life as a globe-trotting, internationally famous model and movie star, living through some of the most exciting and creative times in New York’s history, Shields says that she often felt trapped. She says she never really felt free until she went away to study.

“I think people look at the entertainment industry and the assumption is that it’s a wish fulfillment and that you are living a dream and its freedom, when it really can be the antithesis of that, because nothing is really on your terms,” Shields says. “You’re wearing someone else’s clothes, you’re being told to stand here and do this. You’re being told that you have to get up at 6 a.m. to do that. You’re a kid on an adult, 14-hour-a-day workload. You have to play the game, and then you have to get on camera and act positively. You have to sell. And you’re selling yourself and you’re selling the product and you’re selling other people’s money. You’re doing it all because you have a boss of some kind, whether it’s the public or the owner of a studio. Unless you are the person with all the money calling all the shots, there is no freedom in it.”

“I was very much on the straight and narrow. I was a good girl. I was America’s sweetheart,” she adds. “My approval was based on being a good girl, on being obedient, and you get rewarded for that. It’s better than being in the detention hall of life. But it still wasn’t on my terms. Nothing was on my terms until I got to university.”

Shields’ parents divorced with the condition that her father would pay for her education. So while many of her acting peers dropped out of high school, Shields enrolled at Princeton where she studied French literature. She would later give a commencement address at her alma mater, an experience she says was both nerve–racking and fulfilling.

“I had to go to university. I refused to be denied something that I felt normal people got to do,” she says, acknowledging that not all “normal” people go to Princeton. Before college, she says, “I used to see movies with students and I would think, ‘My god! What freedom it must be to just walk into buildings and have really smart people teach you and make you smart.’”

Shields’ dining room, left, and powder room

An education gave Shields the security of knowing that if it all disappeared, she had something to fall back on. The fact that careers in entertainment are often ephemeral was never lost on her. Everyday, she says, she was aware that the bubble could burst. Of course, it never did.

Today, Shields lives a more leisurely life in the West Village with her family. She resides in a 1910 townhouse house that was gut renovated a few years ago by MADE, a Brooklyn design/build firm with expertise in historic buildings. The project spared much of the home’s original details and showcases many of her mother’s flea market finds.

For fun, she grabs treats at Maison Kayser with her daughters and green tea matcha lattes from Teavana. Dinner is often at L’Artusi or the Waverly Inn.

“I have a lot of fun with my daughters. We just engage with the city,” Shields says. “For as big as it is — for as much theater and performance art as we see, for as many museums that we go to — it feels like a small town for us, because of the way we live in it.”

But while she’s enjoying Manhattan with more freedom than ever before, she has never quit working, nor does she have any plans to.

“You are going to have to drag me away. You are going to have the hearse waiting. I’ll say my last words and you can put me in the box,” Shields says. “Acting is like a blood infusion for me. It was my first love. Before my husband or my kids, my biggest relationship was with performing.”