Zaha Hadid, the Iraqi-British architect whose sinuous designs pushed the limits of building shapes, and who became the first female recipient of the Pritzker Prize, died Thursday. She was 65.

Hadid died suddenly of a heart attack at a hospital in Miami, where she was being treated for bronchitis, her company, Zaha Hadid Architects, confirmed.

Over the last few years, Hadid’s name has often come up in the same breath as giants of architecture such as Frank Gehry, Norman Foster and Frank Lloyd Wright. An obituary released by her firm describes Hadid as the “greatest female architect in the world” whose interest lay in the intersection between “architecture, landscape and geology.”

“She was a great architect and a great friend. I will miss her,” Gehry said in a statement provided to The Real Deal.

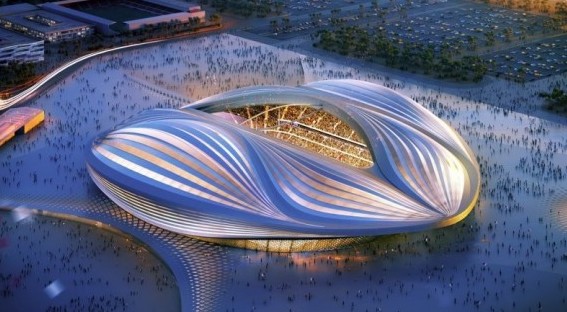

Some of her most notable projects include the MAXXI: Italian National Museum of 21st Century Arts in Rome and the London Aquatics Center built for the 2012 Olympic Games. She is also the designer behind the upcoming Al Wakrah Stadium in Qatar, which will be used for the FIFA World Cup in 2022.

In New York, Hadid designed 520 West 28th Street, a spaceship-like condo rising over the High Line that is being developed by the Related Companies. In Miami, Hadid designed One Thousand Museum, an under-construction luxury condo tower being developed in downtown.

Louis Birdman, a co-developer of One Thousand Museum, said Hadid “knew how to push the bounds of design.”

Ismael Leyva, an architect who worked alongside Hadid on the 520 West 28th Street project, said in a statement to TRD that “her loss will be felt by all those who value the outstanding contributions she made to the built environment.” Jeff Blau, CEO of Related, said in a statement that Hadid’s impact “is sure to be felt for decades to come.”

A rendering of 520 West 28th Street

Born in Baghdad in 1950, Hadid went on to study mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving to London to study at the Architectural Association in London in 1972. After graduation, she joined the Office of Metropolitan Architecture, and it was there that she worked under Rem Koolhaas. The Dutch architect once famously described the flamboyant Hadid as “a planet in her own inimitable orbit.”

“When he said it at the time, I was upset,” Hadid told CNN at in 2014. “But in a way he was right — I should not have a conventional career and he was absolutely spot on.”

When Hadid won the Pritzker in 2004, the jury wrote of her work: ““Each new project is more audacious than the last and the sources of her originality seem endless.” In 2015, she became the first woman to win the RIBA Gold Medal, Britain’s top architecture prize.

Hadid started her own practice, Zaha Hadid Architects, in London in 1979. In her early years, she drew attention for her theoretical designs, such as a recreational center on the Victoria Peak in Hong Kong, which incorporated the cliffside into the building. Her design won the competition for the recreation center in 1983, but the vision was never realized. Further acclaim followed with her first major commission, the Vitra Fire Station in Germany in 1993, and the Guangzhou Opera House in China in 2010.

But the scale and ambition of her visions proved problematic at times. Late last year, her design for the 2020 Olympic stadium in Tokyo was thrown out amid spats over the $2.5 billion price tag. Her Qatari stadium project has drawn criticism for the alleged mistreatment of migrant workers, but Hadid said at the time that “it’s not my duty as an architect to look at” the issue.

A rendering of the Al-Wakrah stadium in Qatar Credit: Zaha Hadid Architects

Her status and demeanor in a male-dominated profession often earned her the label of a “diva” — to which her response was usually a variation of an early famous quote: “Would they still call me a diva if I was a man?”

Architect Peter Cook once described Hadid as “larger than life” and “bold as brass.” He called her immodest and a fierce critic of “poor work and stupidity,” but also a loyal friend. In his 2015 citation commemorating the Gold Medal, he said her early style eventually evolved from “spiky” lines inspired by Russian Constructivism, to the dreamlike, flowing lines that characterize her best-known work.

“For three decades now, she has ventured where few would dare: If Paul Klee took a line for a walk, then Zaha took the surfaces that were driven by that line out for a virtual dance and then deftly folded them over and then took them out for a journey into space,” Cook wrote at the time.

In a 2011 interview with Newsweek, Hadid explained her view of her profession.

“I don’t think that architecture is only about shelter, is only about a very simple enclosure,” she said. “It should be able to excite you, to calm you, to make you think.”

Although Hadid’s work has virtually no standing physical presence in Los Angeles and the surrounding area, her influence is profound.

One of the late architect’s most recent cameos in L.A. was her set design for the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s production of “Così Fan Tutte” in the spring of 2014. Zaha Hadid Architects designed a swooping white dune that served as the stage in Walt Disney Hall. Resembling her avant garde buildings, the undulating runway made, perhaps, a stronger impression than the opera itself.

“It’s a shame that we don’t have deep legacy [of her work here],” David Gerber, who used to work with Hadid in her London practice and is now a professor of architecture at the University of Southern California, told The Real Deal. “She was a force to be reckoned with. There are a lot people here that are mourning and grieving. A close friend of ours has died.”

Ina Cordle and Cathaleen Chen contributed to this report.