Trevor Noah wasn’t supposed to happen. He wasn’t supposed to be the face of “The Daily Show,” Comedy Central’s longest-running and most influential program. He wasn’t supposed to tour the world as a stand-up comedian, because he wasn’t supposed to have left the dirt roads and open sewers of Soweto, one of the many formerly segregated ghettos surrounding Johannesburg. In so many ways, he wasn’t supposed to have survived the absurdities of apartheid. In fact, as a man of mixed race, he wasn’t supposed to exist in the first place.

But Noah was lucky (he might say “blessed”). A little over a year ago, the 32-year-old fresh-faced South African seemed to drop from the sky and land behind the desk of “The Daily Show.”

On the strength of just three appearances, he became the network’s surprise pick to

replace Jon Stewart, who over 16 years had grown the show into a cultural phenomenon. The timing couldn’t have been more perfect for a political comedian looking to sharpen his talons — Donald Trump would soon descend the golden escalators of Trump Tower to announce his presidential campaign.

Bolstered by his viral takes on what was surely the most surreal presidential election in U.S. history, Noah is now impossible to miss. He’s on your television screen. His clips are on your Facebook feed. His face is on billboards, buses and subway placards. And now his book is in your bookstore — assuming those still exist somewhere.

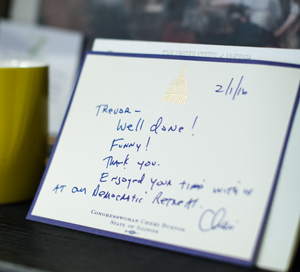

A thank-you note from a guest on his show

Noah’s new book, “Born a Crime,” is out this November. It’s sort of a nonfiction coming-of-age story, chronicling Noah’s adventures with his no-nonsense mother, his distant father, his murderous stepfather and his break-dancing buddy with the improbable name of Hitler. Against the background of bitter poverty and apartheid horrors — where blacks weren’t simply made second-class citizens; they were made noncitizens — Noah describes the universal experiences of youth: first loves, the struggle to fit in, friendships…and the odd trip to jail.

Luxury Listings NYC met up with Noah backstage at “The Daily Show” during a haircut to discuss his new book, his first year behind the host’s desk and the triple crown of holiday-season taboos: race, religion and politics.

…..

Noah’s new life in the U.S. is just beginning. He moved to Los Angeles in 2011, and into a swank Hell’s Kitchen rental near work just one year ago. He’s still getting to know the city. Some nights he drives to Williamsburg for Caribbean food at Pearl’s. On others, he grabs a drink at Ardesia Wine Bar, on the West Side, after the show. He’s getting into the stride of life as a celebrity, the gymnastics of being mercilessly scrutinized and applauded simultaneously. So, in some ways, it is a strange time to release what might be considered a memoir.

“To come from my world and to be

sitting across from a former president and to be

asking questions, that’s insane for me.”

It’s just that “that stage of my life is finished,” Noah explains. “I only realized when I was done, but it really is a story of a mother and a son. I thought it was my story, but it was our story.”

Dissecting the day’s news on his nightly show, Noah is often as serious as he is comical. It’s a strength of the show pioneered by Jon Stewart. But off camera, Noah is perhaps more sober still. His answers are often short and pensive, delivered unsmilingly even when they end with a quip.

“I don’t find many of my stories interesting,” Noah adds after a long pause. “People go, ‘You lived an exciting life!’ And I say, ‘We all lived exciting lives in South Africa.’ ”

He has permission to be jaded. He grew up eating dog bones for dinner and occasionally Mopane worms (thick African caterpillars the size of a finger, “literally the cheapest thing only the poorest of poor people eat,” he writes, “they’re fucking disgusting”). Walking to school, he grimaced at the melted corpses of men burned alive by rival ethnic factions. Barred from taking whites-only public transportation, he risked his life taking gang-run minibuses to church. That was everyday life for many poor South Africans. But needless to say, Noah’s stories are objectively “interesting” to anyone who has spent life in the comfort of more fortunate circumstances.

TAKING A BREAK: Noah gets in a quick workout on his Stamina X Fortress Power Tower, wearing a Paige T-shirt in black, $75, and cotton linen pants in dark sapphire by Original Penguin, $98.

Noah was a criminal, along with his mother and father, the moment he was born. In South Africa, miscegenation was strictly illegal. His mother was Xhosa. His father was Swiss. The penalty for their family was years of prison.

He spent his early childhood in hiding. He couldn’t be seen with his father in public. Once, he yelled “Daddy!” at the zoo. His father had to run.

As he got older, he both benefited and suffered from the predicament of his skin. Technically, Noah was “Coloured,” which refers to someone of mixed race under the apartheid system. But he lived in a black neighborhood. His mother was black. And he identified as black. That meant other Coloureds would not accept him, and many blacks treated him with absurd respect. His grandfather would call him “Mastah.”

“In the car, he insisted on driving me like a chauffeur. ‘Mastah must always sit in the backseat.’ I never challenged him on it. What was I going to say? ‘I believe your perception of race is flawed, grandfather.’ No, I was five. I sat in the back,” Noah writes.

Noah on the cover of New African magazine

As a teenager, he became an illegal mix-tape kingpin, raking in enough cash to get his first taste of the good life, aka McDonald’s. He ran in a dance crew led by the aforementioned Hitler (not an uncommon name in third-world countries where your English name is of little significance and usually chosen from the Bible or the news). He deejayed illegal street parties in more dangerous ghettos. He flipped stolen goods and even started a payday-loan operation on the street.

Mix-tapes and parties led to radio shows. Radio shows led to small acting roles on South African soaps. Acting led to stand-up comedy, and comedy led to New York City. He’s lived fast and intensely.

“People who were very poor, or lived in third-world countries, their stories will generally be more exciting than the average person’s,” Noah says. “I don’t think that diminishes anyone’s experience, because we all experience the same things in different ways: self-doubt, first loves, being ostracized or alone. That plays itself out no matter where you live in the world. There are just some

extra things when you’re poor.”

“Hashtag first-world problems,” he says after another long pause. “They’re still problems. It’s a problem to you that you can’t find gluten-free bread. That is a big problem in your world. It might stress you out as much as me not being able to find food stressed me out, because of our perception of the problem.”

Noah’s new book, “Born a Crime,”

describes how, as a man of mixed race,

he wasn’t supposed to exist in the first place.

The new chapter of Noah’s life is even more intense. He’s touring, performing stand-up on his off nights. He’s working with “He for She,” a women’s advancement campaign initiated by the United Nations and backed by actress Emma Watson. He supports the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund and grassroots soccer programs in Africa. He travels. He loves Nashville. But it’s NYC, he says, that he finds really amazing.

“It’s high energy, crazy, crazy pace,” he says. “NYC teaches you to be more efficient in your living. New York teaches you to find the most efficient way to work out, the most efficient way to walk somewhere, the most efficient way to eat, the most efficient way to drink. It is almost like you can live two lifetimes in New York. It really compresses everything. It condenses life. You experience so much in so little time.“

…..

Much of Noah’s childhood was spent verbally sparring with his extremely free-spirited, VW-bug-driving mother. The topic was often religion. Patricia Noah is a Jesus freak. Occasionally, demons would need to be banished. Sometimes the devil would need to be fought. Always, church would be attended — to be precise, three of them, many times a week.

Trevor Noah

Noah’s relationship with religion is more nuanced than his mother’s. He admired the strength Christianity gave his mother in the face of unbelievable odds. But he was frustrated by the seemingly arbitrary rules built into traditional practice. After being denied the Eucharist, he once crept into the chapel, drank all the grape juice and ate the host.

Still, Noah rejects atheism. He ruffled the feathers of many “Daily Show” fans when he tweeted, “Without God, Atheists wouldn’t exist,” “#Weallneedgod” and attacked the late author and prominent anti-theist Christopher Hitchens.

However, Noah tells me that he is not a Christian. “I think spiritual is the word I would use,” he says. I ask what that means.

“It means I believe in something greater than myself,” he says. “I meditate, and when I look at it, meditation is basically like prayer. It is funny when people tell me they are not religious and I go, ‘Do you believe in luck?’ And they go, ‘Yeah.’ I say, ‘Well, just think of luck and imagine if a religious person replaces luck with God: How did that happen? I was lucky. Versus, I was blessed.’ That’s really all it is.”

Lucky or blessed, Noah says he witnessed at least one miracle.

A billboard of Noah watches over the studio;

In 2009, his stepfather, Ngisaveni Shingange, drove to his mother’s home and shot her in the back and the face in front of her family. He continued to fire, but the gun jammed. The police couldn’t understand it, Noah says. The gun shouldn’t have misfired. It appeared to be in perfect condition. Shingange fled.

In the hospital, his mother’s doctor told Noah there was nothing he could do, because “there was nothing he needed to do.”

Not only did the gun misfire, but the bullet in her head missed her spinal cord and her medulla oblongata. It missed her brain and her eye, too. Instead it ricocheted off her cheekbone and came out her nose.

“I don’t like to use this word, because I’m a man of science and I don’t believe in it. But what happened to your mother today was a miracle,” the doctor told him. “I never say that, because I hate it when people say it, but I don’t have another way to explain it.”

She was back at work in a week.

…..

Every weekday, before “The Daily Show” starts, Noah greets the audience with a short Q&A.

“What’s your spirit animal,” one guest yells.

Noah fires back: “Oh wow! My spirit animal is a panda. It’s black and white, and it can’t have sex while people are watching.”

He is a master of delivery. He comes alive on stage. Every day, the line for tickets wraps around the studio on 11th Avenue and 52nd Street. But after a year behind the desk, the show has struggled to build back its reputation without Stewart at the helm.

Still, while some have bemoaned the loss of Stewart, Noah says that in many ways little about the show has changed.

“Jon and I are a lot more similar than people think. We discovered that ourselves,” he says. “We just happen to be born in different places and lived different lives. But we connect in our comedy, worldview and ideas. If anything, Jon saw himself in me. That’s what he told me.”

One change that can’t be denied is that for the first time in 10 years, “The Daily Show” was not nominated for an Emmy.

“Who gets nominated in their first year?” Noah says. “That’s a weird thing to me. People go, ‘Oh, you didn’t get nominated!’ And I go, ‘Yeah, because how would that make sense?’ Your saying I should get nominated implies that Jon [Stewart] getting nominated wasn’t actual work. It is a very difficult process. That is something I don’t take for granted.”

He says that Trump’s “storm front of buffoonery,” while undoubtedly a wellspring of comedy, may have hurt the show.

“It doesn’t help that the news has been so one-dimensional and that it is just Trump,” Noah says. “I remember when we started, there was so much more happening. And now it feels like if you had a plasma-screen TV, the word Trump would be burned into your screen by now.”

He says he considers the show, and comedy in general, somewhat journalistic. It requires research. It exposes the truth. But ultimately he says that his show relies on journalism and the media often gives him little to work with.

“The media enjoys this ability to create fanfare, and the other day was a good example,” he says. “They covered Trump’s podium for an hour before he said anything. They could have been covering other things. They could have been talking about other stuff. But they didn’t.”

Nevertheless, Noah has also devoted much of his show to mocking Trump’s presidential campaign. But he says in some ways Trump’s stampede into politics is no laughing matter.

“I take him seriously. We live in a world of nuances. It’s not just black and white: ‘Is he dangerous? Is he not?’ ” Noah says. “Just because Donald Trump is a clown doesn’t mean that he’s not dangerous. It is just like in horror movies. There is a clown, it’s funny; you can’t deny it. The nose looks funny. The face looks funny. It does funny things. But it can still kill you. Trump has the ability to be a clown and to be dangerous as well.”

In the post-Trump era, Noah says, his ambition will be to make the show as engaging and funny as possible. He promises to go places that “The Daily Show” never could in the past, to push the envelope on identity politics.

“I am more into social politics. I can have conversations about race that Jon couldn’t have. I can speak to different experiences. I speak from a worldly perspective,” he says. “[I want to] engage people’s minds, making them go, ‘I didn’t think of it like that,’ while also being funny.”

…..

Noah calls friends in South Africa every day, because he knows jobs in show business exist on a razor’s edge. Most shows, like most careers, are here today and wiped from the airwaves tomorrow. So it pays to hold on to your roots.

“What will never go away is your experiences and the amazing moments and people,” he says. “If you think you’ve made it, then what is the point of carrying on?”

Modesty is one way of not losing yourself along with your job. Lots of successful people boast that they came from nothing. But there is America nothing and then there is Africa nothing. And extraordinary triumphs often lead to extraordinary egos. Noah says the brutality of live comedy and encounters with extraordinary figures are the antidotes to self-importance.

“Interviewing Bill Clinton, a former president! Do you know how crazy that is for me, coming from my world?” he says. “I have to take a second and go, ‘I guess this is normal if you are a late-night host.’ But to come from my world and to be sitting across from a former president and to be asking them questions, that’s insane for me.”

Call it fascinating or tragic, Noah’s ascension to one of the most influential seats on television is a pinpoint on the map of progress. Preying on America’s enduring Anglo-inferiority complex, media executives have long imported British Commonwealth personalities to add a touch of elitist panache to sitcoms and cinema alike. But Noah represents something new in that formula.

His strength isn’t his accent; it’s his nearly complete otherness. Essentially a parvenu, but he can speak about poverty because he knows it. He’s an émigré, a racial minority, but who better to give a disinterested take? Who better to see the larger view? Maybe that is where good comedy exists anyway.

Noah has arrived at the hour in American politics when we most need a global mirror. We need truth-seeking comedy, cosmopolitan comedy, comedy that can contextualize a police shooting within a world of tragedy. We need comedy through the looking glass.

“The world we’re in is ridiculous,” Noah says, “so I am going to be ridiculous right there with you.”