The Box, Manhattan’s most notorious club and variety show, just turned 10 years old. Owner Simon Hammerstein, grandson of musical-theater legend Oscar Hammerstein II, took us inside the sinful night world he created and tells us why his message of libertinism matters more than ever.

“Christopher, we’ve been expecting you,” the bouncer outside the notorious Lower East Side club says, unlatching the velvet rope. Inside, a woman in a showgirl outfit draws back a curtain. “Welcome to the Box,” she says.

It’s a little after midnight, and it’s my first time to the Box. I’m nervous. The Box, like Studio 54 or the Limelight, is a place where legends are born. Friends and colleagues have whispered stories of fully nude waitresses, silver trays of cocaine and live sex shows. Like a lot of legends, they’re probably born of truth.

I’ve wanted to visit the Box for years, ever since a dear friend began working on a film for the Slipper Room (another neo-burlesque variety-show theater, just three blocks from the Box on the Lower East Side). She enchanted me with tales of larger-than-life performers— drag-queen beauties, pissed-off transsexuals, freak-show oddities — who split their time between the two venues. But I had always balked at the price of a table at the Box — $1,200 minimum plus a 20 percent service fee. Revelers are welcome to line up outside for the 1 a.m.-to-4 a.m. show, but I don’t believe in waiting in the cold for a bouncer to size me up. My nightclub motto is “Come with an invitation or don’t come at all.” I finally had my invitation.

Simon Hammerstein (Photo: STUDIO SCRIVO)

Behind the curtain, a woman dressed in black panties, a loosely buttoned white dress shirt and a small, feathered top hat leads me to table six, a booth at stage right. She brings a bottle of Perrier-Jouët to my table and pours each of us a glass. She holds my hands, looking into my eyes and touching my chest. Thumping club music forces us to speak directly into each other’s ears. “What brings you here tonight?” she asks. “I’m writing about Simon,” I tell her. She feigns surprise and asks me if what I’m writing is good or bad.

Hammerstein, 39, materializes a short time later in drag. He’s wearing a white dress with a long slit up to the waist and glitter on his chest. He sports shaggy dark hair and thick black whiskers. His gestures are big and loose, and he speaks softly with a transatlantic inflection.

“Sorry, I’m drunk!” he tells me. He squeezes into the booth with two more girls and starts pouring tequila shots.

As the show begins, Hammerstein loudly heckles the performers. “Get off the stage!” he yells. “Fuck off! Fuck off and die!” “Your mother sucks cock!” They seem to take it well, either firing back at the audience with strings of profanity or ignoring the abuse, familiar with Simon’s rotten-tomato routine.

“I curse out the show to create more tension in the room. I’ve been doing it for years,” Hammerstein tells me. “It has really upset my performers, because they thought it was a customer being offensive to them, and when they find out it is me, they are doubly angry. Of course, I’m doing it with the idea of creating as much drama in the house as possible. But it can upset people.”

The performances themselves range from astonishing circus acts to X-rated neo-vaudevillian romps. A little person and a third-generation circus performer playact father-daughter incest, kissing with tongue before attempting to balance the “father” on his head on a basketball atop a tower of Champagne bottles. A transsexual aggressively removes from an orifice a large tampon that shoots a puff of glitter. A contortionist shoots a bow and arrow at a balloon with her feet. An aerialist does a burlesque routine while twirling above the room.

Hammerstein pours more shots as the music returns between acts. He tells me that it’s a show you need to be drunk to appreciate, and I’m willing to oblige. I accept another drink as a tall transsexual dressed like Anna Wintour approaches our table. She takes one of our glasses and spits into it. The crowd jeers, but Hammerstein warns me not to provoke her. Now onstage, she disrobes quickly. Squatting over a prop toilet, she takes a long shit into her panties. She rubs the mess over her body and struts around. I’m suddenly glad not to have a front row seat.

“People walk out all the time,” Hammerstein tells me. “People storm out. Probably once a night we’ll have a table that’s spending good money leave. And at most clubs they would do everything they can to coddle someone spending $3,000 or $4,000. But for us, the brand, the politics of life as told through the show and our respect for our staff comes first.”

* * *

During my interviews with Hammerstein — at his home, at his favorite café, on the phone and at his club — he rarely shied away from any question I threw at him. So many people seize up and attempt to reinvent themselves in front of a reporter. To his credit, Simon often responded with uncensored honesty.

But because of that, it would be so easy to write another faux-righteous rebuke of Hammerstein and his club. New York magazine called him an “impresario of smut” and ran the headline “Has Simon Hammerstein crossed the line?” Implication: yes. Meanwhile, a more inured New York Times article suggested in 2007 that the club had lost its bite — less than a year after it opened. Anyone labeled “edgy” is always an easy target.

“What happens in nightclubs is that every other year you are cool,” Hammerstein says. “You are really cool the first year, and then everyone is so pissed off…But in six months or a year, everyone comes back, and we are retro and cool again. I have lost track of if I’m cool or not.”

Au courant or passé, Hammerstein is less interesting as another Manhattan playboy than as an artist, or at least someone very dedicated to enabling free artistic expression. His so-called smut shows come with the moral blackmail of self-reflection. It’s a club where tomorrow’s hangover comes with a lot of “big” cultural-studies questions.

Hammerstein says he believes in creating a theater of contradictions: performances that are therapeutic and challenging, shows that are crass and sublime.

“What are the goggles you want to see [theater] through at 1:30 in the morning?” Hammerstein asks. “Cruelty? Theater of the absurd? Theater of the sublime? We have performance art, physical comedy, musical theater. But all of those things have to be layered with stuff that is going on right now.”

Hammerstein argues that the Box and the art that is created there are nothing more than a dreamlike reflection of the world outside its unpresuming black double doors at 189 Chrystie Street. Just as Dada mocked the seemingly irrational horrors of World War I, just as punk rock channeled working-class rage against Margaret Thatcher, Hammerstein hopes the Dionysian spirit of the Box will be ground zero for an artistic war against Donald Trump.

The anniversary party attracted celebrities and brought back favorite acts.

“The 10-year anniversary was a real moment of reflection for us,” Hammerstein says. “What do we represent now?…It’s a very scary time for people, and we aren’t just going to tap-dance our way through it. We are going to address it.”

The anniversary party, which attracted hard-core Box fans like Zoë Kravitz, Susan Sarandon, Josh Lucas, Lindsay Lohan, Maxwell Osborne, Domingo Zapata and Damian Loeb, as well as a file of journalists, brought back classic acts to the theater. A potpourri of condoms, wrapping papers and rolls of toilet paper covered the club’s surfaces. Former Box MC Raven O returned for the occasion, shouting like a kookaburra. “Get loose for this one!” he yelled. “Smoke some weed…do some cocaine!” Although I left around 3 a.m. — before some of the more extreme acts — it was a safer and more celebratory night than my previous experience at the club. Hammerstein says that he is still figuring out exactly how he should be addressing the new authoritarian zeitgeist.

“How do you address serious topics through irony?” Hammerstein asks.

Hammerstein with Zoe Kravitz

“I think today it’s not even comedy. Ultimately, people do what they have to, to have a great time at your show. You don’t want to hit them over the head with some immigration thing. But you do want to address that…We’re figuring out how to layer in all the things that are going on with all the performers, gay, black or white. It’s a very passionate time.”

* * *

I first met Hammerstein on a cold evening at Jack’s Stir Brew Coffee, near his bachelor pad on Water Street in the Seaport. We talk about booze (he says he drinks Lagavulin 42, a vintage that doesn’t appear to have ever been commercially bottled), theater and love. The Verve’s “Bittersweet Symphony” fills the gaps in conversation. It’s not long before we decide to head back to Hammerstein’s apartment for a more relaxed conversation. “Wonderful. I can smoke indoors,” says Hammerstein, who chain-smokes filterless, roll-your-own cigarettes, with a smile like a naughty schoolboy.

A glass elevator opens directly into Hammerstein’s apartment. There’s a mattress on the floor and a small office piled to the ceiling with this and that. A large library of plays, criticism and pulp fiction leads to his living space, a loft-like room with couches on one end and a kitchen on the other. Art by Zapata, Loeb, Harland Miller and others covers the walls. Hammerstein says he is planning a renovation to make the apartment “less childish.” We lie back on either end of an oversized white couch and smoke.

“I think that in the Obama administration, the kind of evil-powers-that-be were behind closed doors, so we didn’t have to confront it,” Hammerstein says. “Even though Black Lives Matter was formed during the Obama administration, it still felt like we were going forward as a civilization. Now, it feels like we have taken a big step back and the Supreme Court has put their Klan hoods back on in public. [But] my black friends and co-workers say, ‘Dude, nothing’s changed. Shit was sucky then, too. It’s just not pretend anymore. They’re not trying to hide it.’”

Nadezhda Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot performed at the Box’s anniversary party.

Hammerstein seems to have always felt at home with people who were different from him. He mentored a young African-American man in the Big Brother program. Some of his first experiences in theater were directing shows about young men with AIDS in the African-American community at the Soho Repertory Theatre. He was uncommonly young, only 18 at the time. “I don’t know why the let me direct those plays. But they fit me,” Hammerstein says, noting that he always had a penchant for drama.

“As a kid, I would go to school dressed up as Yoda or Batman. I couldn’t leave the house without dressing up as a superhero. It was kind of weird for my family,” Hammerstein says. “I have always liked costumes and dressing up, being irreverent.”

He was born in London and raised in New York, near Mercer and Prince in Soho. His parents were director James Hammerstein and actress and producer Dena Hammerstein (known as Geraldine Sherman in her movie roles). His grandfather Oscar II and partner Richard Rodgers essentially invented contemporary musical theater with shows like “Oklahoma!” “The Sound of Music,” “South Pacific” and “The King and I.” His great-great-grandfather Oscar I built the Hammerstein Ballroom in 1906 as the Manhattan Opera House.

Artwork in Hammertein’s home includes a piece from Lights of Soho

His childhood was privileged and lawless. At 8, he set up a table outside his parents’ apartment labeled “The Crazy Art Stand,” where he sold his elementary-school classmates’ art for as much as $800. He once brought in $1,800 in a day.

“My parents didn’t have rules,” he says. “To get a sense of where the boundaries were, I had to push so far.”

At 11, he was sent to the Bedales boarding school in Hampshire, England — a school Tatler magazine called “a bohemian idyll with bite.” He dropped out at 16 and never received his high-school diploma. As an alternative to school, he threw raves in Bushwick and on the Lower East Side.

“This is the early ’90s, and hip-hop was huge. Mobb Deep and Biggie Smalls, that was my life,” Hammerstein says. “But you couldn’t be into the hip-hop scene without feeling like you were fronting. People would be like, ‘Who is this white kid from Soho going to Zulu Nation parties?’ So the rave scene allowed the white culture in the boroughs and ’burbs to have a version of street life, to have an underground world.”

But in the late ’90s, the rave scene changed as a result of crack cocaine, ODs and fights. He continued to work in theater, directing shows late at night when venues were cheap or free. And it was that strange marriage of rave culture and midnight theater that inspired him to open the Box.

“When I started the Box, I was a theater director, and I wanted theater to be fun for my generation. We wanted to rail against judgment,” Hammerstein says. “I was really trying to figure out the audience for my work and my voice. We did theater in a club setting, and it just took off.”

He had 40 original investors in the Box, adding partners as costs ballooned from an opening budget of $600,000 to $4 million.

“I was so green,” Hammerstein says. “If I was anywhere and the guy or the girl looked well dressed, I would be like, ‘Hey, you want to invest in a project?’ And a lot of them did.”

The Box has let Hammerstein live a certain vision of Downtown glamour, guarding a rotating door of artists, celebrities and models. He’s met his idols, like “South Park” creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone, director Terry Gilliam and Mick Jagger. John Legend, Kanye West, Adele, Chris Martin, Alan Cumming, Snoop Dogg and Katy Perry are just a fraction of 1,000-plus boldface names who have performed at the Box over the last decade. He’s entertained over a million customers and popped 80,000 bottles of Champaign.

“The best is when people get up onstage and perform apropos of nothing,” Hammerstein says. “Kid Rock was there one night, and we gave him a guitar…He got up onstage and started talking and singing. I was like, ‘This guy is a star.’ He was great, a real artist. You don’t really appreciate what artists these guys are until you get them into a small venue.”

But when you are pushing the boundaries, on stage and off, not everyone will be a fan.

* * *

“I don’t give a shit what you write about me,” Hammerstein tells me around 4 a.m. at the Box after a night of heavy drinking. “You can call me a rapist. New York magazine already did. You can call my mother a whore. New York magazine already did. There’s nothing you can write about me that will hurt me. In fact, it’ll just be good for business.”

But after several subsequent calls and texts, it’s clear that he does care very much.

“I have so much pride in the brand and the product,” he tells me on another occasion. “We don’t do marketing. We have never done any advertising. So it is imperative that people go and recommend the show to their friends every single night, that everyone who leaves becomes an ambassador. You can’t just take the show or the service for granted.”

And for the record, New York magazine didn’t call Hammerstein a rapist. The story he is referring to is a 2008 article by Alex French, who did not respond to LLNYC’s request for comment. In his profile of Hammerstein, French investigated accusations of sexual assault made by the Porcelain Twinz.

The twins, named Amber and Heather, were known for their fetish burlesque routine “Twincest” and for a time even lived with Hammerstein. “We had a smoking-fetish show,” Amber told New York magazine. “It involved toys, but it was always just simulated contact. Simon was like, ‘Can you do it for real?’” They made other accusations, including that Simon pressured them into a ménage à trois.

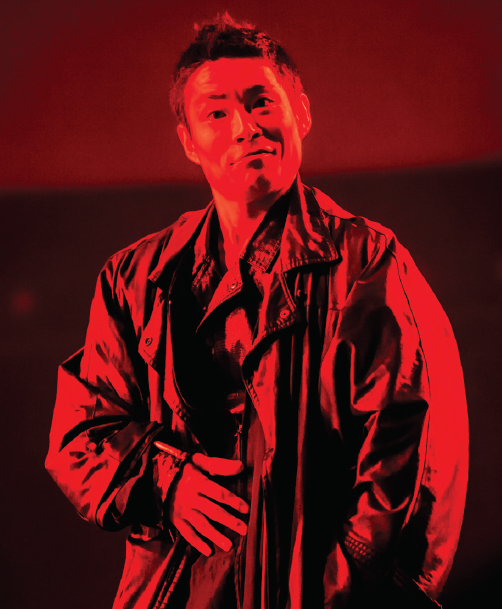

Kenichi Ebina

Hammerstein has always denied any wrongdoing, and he says he was deeply hurt by the accusations. But it is easy to see, in the drunken and sexually charged environment at the Box, how personal boundaries could be crossed. And Hammerstein often jokes about the litany of litigation he has faced over the last decade.

“You’ve got to remember that dealing with people who want to be part of a family, of a night circus, that it’s a lot of personality and a lot of vulnerability.” Hammerstein says. “When you are pushing the boundaries onstage, you are playing with a certain kind of energy that can go in a lot of different directions. We all get upset about stuff and we want to address topical stuff, but we all have different backgrounds. It’s like when Mel Brooks put the singing Nazis in ‘Springtime for Hitler.’ As a Jew, I find that very funny, but maybe if my mom was from a camp I wouldn’t find that funny. We are all trying to find a shared message coming from very different backgrounds.”

Many performers and patrons have stood up for Hammerstein, either directly, like Box fixture Rose Wood (the performer who dressed like Anna Wintour for her raunchy act on my first visit to the Box), or indirectly, with their continued financial and creative support.

“I’ve worked in some clubs where I’ve been given three prostate exams before even taking off my coat. Simon is just a vanilla boy,” Wood told New York magazine in 2008. Wood made headlines herself in 2010 after she vomited on actress Susan Sarandon during her performance. Sarandon seems to have taken it well, as she returned for the Box’s 10th-anniversary blowout.

Hammerstein was reluctant to introduce me to performers. But Box veteran Kenichi Ebina agreed to meet me at an apartment above the venue at midnight to tell me about his experience at the Box.

Ebina, who won season eight of “America’s Got Talent” for his act that combines dance, martial arts and mime, told me that the Box helped him take the act to the next level.

In one of his acts for the Box, Ebina, who is a small Japanese man, passes for a female belly dancer. A twin (actually female) belly dancer joins him and they do a sultry dance that turns into a striptease. Eventually they are fully nude, revealing that Ebina is a man. “Then we start fucking!” Ebina laughs. “But not real fucking.”

Ebina lives in Japan now and travels around the world performing at private parties for the likes of Madonna or the royal family of Monaco. But he says that when he is in New York, he likes to come back to the Box.

“I feel at home here,” Ebina says. “This is the venue where I have performed the most and the longest. What they do is very crazy and hard-core, but I feel like family when I’m back here.”

My conversations with Hammerstein left the impression not of a sleazy nightclub impresario but of a deeply self-conscious man, allergic to censorship, unafraid of judgment and committed to creating thought-provoking art.

“America is so fucking puritanical,” Hammerstein says. “We can go to the movies at 12 years old and see a 100 people get shot, but we can’t see breasts. What the fuck does that say about our culture? Let’s celebrate murder and not celebrate the natural woman. It’s shocking to me. [At the Box] we are confronting the puritanical conceits that we may not even realize have conditioned us.”

* * *

Hammerstein separated from his wife, Francesca Zampi, five years ago. More recently, he landed in the tabloids after dating “Harry Potter” star Bonnie Wright. That relationship also dissolved. Now, Hammerstein says, he’s in the midst of a transition. He’s meditating, trying to cut back on the partying (although I witnessed no evidence of that) and says he’s done with chasing love.

“I’m trying to simplify my life a little bit and not be so outrageous all the time,” he says. “I think you spend your first 40 years trying to kill yourself, and now that I’m on the cusp of 40, I’m like, ‘Maybe try and live a little longer?’”

He’s also busy trying to expand his brand. Hammerstein’s London club, also called the Box, is still one of that city’s wildest nightspots. But attempts to open versions of the Box in Dubai and Las Vegas failed. Hammerstein says the Dubai venture was a disaster, receiving an $80,000 fine when his dancers performed the seemingly innocuous cancan. His Las Vegas club, the Act, was shuttered after Hammerstein’s landlord, the Las Vegas Sands, claimed that his performers were in violation of the Nevada’s obscenity laws — obscenity laws in Vegas?

And back in New York, Hammerstein’s upscale dinner show, “Queen of the Night” at the Paramount Hotel, recently ended its run. But Hammerstein has a new venture up his sleeve that he’s hoping will take his world back to the big stage.

The new project is on 57th Street, and it’s a similar show to “Queen of the Night,” Hammerstein says, noting that he just signed a 25-year lease on the venue. “We are trying to mix multiple mediums. We are going to be using theatrical food and drink, and sleight of hand and illusion. I have always loved magic as an art form, so I wanted to infuse it with that.”

But don’t expect David Copperfield. “I am going to rebel against that aspect of magic,” he says. “For the last 100 years of magic, they’ve been letting people know that it is trickery and that is not real. And yes, even though I might not really make someone disappear, I would like you to believe. I’d like you to think about what magic is and what are we looking for in our own sense of spirituality.”

* * *

From the surreal eroticism of Félicien Rops to the violence of Viennese Actionism, the avant-garde art of the last century sought to undermine and shock. But the bourgeoisie of this century is not so easy to nauseate. The distinction between high and low culture has melted away, and the rich and aspiring cement their status directly through the consumption of pornographic, outrageous or lowbrow kitsch objets d’art. Long live Gagosian! And so much for “épater la bourgeoisie!”

The Box is certainly set within this new paradigm of haute-bourgeois shock consumption. Celebrities in black tie order $2,200 magnums of Dom Pérignon to watch a transsexual sit on a whiskey bottle. But with a nose for holy cows and a twisted sense of humor, Hammerstein has almost inconceivably found a way to provoke nonetheless.