Michael Alig, 51, the former provocateur-in-chief of New York’s party scene, is wrapping up dinner at the restaurant Sauce on the corner of Rivington and Allen streets on the Lower East Side. It’s 10:30 p.m. on a Monday, and we are heading to the party he’s hosted once a week for the last seven months at the nearby Rumpus Room.

“Can you throw a party in an abandoned subway station today, or is that terrorism?” Alig asks the small group he’s gathered to discuss the future of creative nightlife.

Baby-faced and dressed in a tie and polka-dotted shirt, he speaks quickly, almost staccato. His guests seem slightly in awe.

“I think you definitely will get arrested for that now,” says a man simply called Lobster.

As the ringleader of the so-called Club Kids — a group of flamboyant nightclub celebrities — Alig rapidly rose to become the most creative and controversial figure in New York’s legendary, anything-goes, amoral late-’80s and early-’90s scene. But his ascent met with a Promethean fall in 1997 when he pleaded guilty to manslaughter. And now, after being locked away for nearly two decades and off parole, Alig is back, promoting parties, writing, painting and grappling with a New York City that seems to have sobered up in his absence.

It’s almost impossible to summarize the seemingly never-ending supply of Page Six headlines, outrageous apocrypha and established facts about Alig. But perhaps the easiest way to weigh his impact as a young club promoter, and his enduring relevance, is to point to his impact on fashion and pop culture.

Alig and his crazily named retinue of revelers, like RuPaul, Keoki, James St. James, Freeze, Angel, Richie Rich, Amanda Lepore, Genitalia, Ernie the Pee Drinker, Junkie Jonathan and Woody the Dancing Amputee, pushed the boundaries of drag and fashion. They dressed in “apocalyptic chic,” often with campy gas masks and fake blood. They were offbeat and irreverent. They smeared their lipstick and wore negligees on their ears and earrings on their exposed genitals to outlaw parties thrown in anti-glam non-venues like the Burger King in Times Square. Their raison d’être was shock.

Village Voice writer Michael Musto, who chronicled the rise and fall of the scene, called it a “cult of crazy fashion and petulance,” the influence of which can be seen today in the wardrobes of Marilyn Manson and Lady Gaga.

“I got a call one day last year saying Marilyn Manson wanted me to come to Terminal 5 for a performance, which I thought was a little bit weird,” Alig tells LLNYC at another Lower East Side bar. In the middle of the show, Manson stopped performing and said “he wanted to dedicate the rest of the show to somebody who allowed him to become ‘Marilyn Manson.’ And he said my name.”

“I really thought it was some kind of practical joke. He said that he never knew how to wear his makeup and that his clothes were all wrong, but that I always made him feel like a celebrity.”

But in the eyes of many, Alig remains taboo. In March 1996, Alig helped kill his friend, roommate and drug dealer Andre “Angel” Melendez. High on a cocktail of narcotics in their Hell’s Kitchen apartment, Alig and Angel got into a dispute. It quickly turned violent, and fellow Club Kid Robert D. “Freeze” Riggs intervened with a hammer. Angel fell down unconscious.

“Mr. Alig then throttled Mr. Melendez and poured a detergent into his mouth before wrapping it with duct tape. The two men then dumped Mr. Melendez’s body in their bathtub,” according to a contemporary New York Times report. While it has often been reported that it was Drano, not detergent, poured into Angel’s mouth, Alig says that he poured Drano and baking soda over, not into, the body to mask the smell.

In a published account of the incident, Alig writes that after letting the body sit for days, they had 20 bags of heroin delivered. “We did bag after bag. ‘I hope I overdose tonight. Then you are going to have two bodies to get rid of,’” he remembers telling Freeze.

Alig then skipped town on a Special K, cocaine and heroin bender. Angel’s remains were recovered later that year. Alig was arrested in a New Jersey motel. He was suffering from severe heroin withdrawal. He pleaded guilty in State Supreme Court in Manhattan to one count of first-degree manslaughter. Alig served 17 years in prison for his crime.

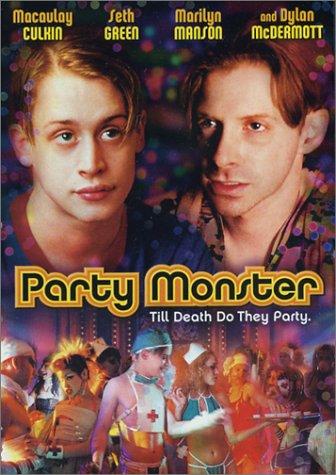

The horrific crime would leave an indelible mark on society. It served as the inspiration for the 2003 film “Party Monster,” starring Macaulay Culkin, Seth Green and Chloë Sevigny. Despite the film’s macabre subject matter, it served as a guidepost for young people starved for unfettered fabulousness. The film introduced Alig’s antics to an international audience and cemented the Club Kid brand. Similarly, St. James’s memoir of his days as a Club Kid, “Disco Bloodbath: A Fabulous but True Tale of Murder in Clubland,” is now a cult classic. Two popular documentaries were made about Alig’s fall, “Party Monster: The Shockumentary” and “Glory Daze: The Life and Times of Michael Alig.”

Not unexpectedly, Alig dislikes the way his story has been told by filmmakers. He tells LLNYC the film “Party Monster” is “one-dimensional” and, more surprisingly, that it short-changes Angel, making him into a minor side character.

“I always wonder how Angel’s family feels when they see it,” Alig says with evident remorse. “Because it is so not about him. I know how my mom would feel if that was me, and she would never get over it.”

“I think I have been treated pretty fairly,

maybe more so. I can’t really complain.”

Likewise, he says the makers of the documentary “Party Monster” deliberately took him out of context, editing a longer clip down to the quip:

“We were at the Royalton Hotel and they said, ‘Say something for the cameras. Tell us why you killed Angel.’” I said, ‘Oh, you want me to say something shocking like, he was [a] copy cat so we killed him.’ They took it so out of context. It was disingenuous. They made me look like a sociopath, when in fact I was being the satire of a sociopath.”

Nevertheless, he admits that the books, TV specials and films surrounding his club days and crime have inspired a whole new generation of fans. As we walked through the Lower East Side, everyone we passed, old and young, stopped to kiss Alig’s ring. An older man who went with Alig to his first party in 1984 happened to walk by — they hadn’t seen each other in 35 years. The ball may be smaller than in was in 1996, but Alig is still the belle.

“When you take into consideration the reality of the situation, I think I have been pretty fortunate,” Alig says of his life following his release from prison in 2014. “I think I have been treated pretty fairly, maybe more so. I can’t really complain.”

Alig insists that there is no other option but to be gracious about his situation. He’s returned to the disco, his first love. His weekly Outrage parties mock the internet and social media outrages du jour (a framed picture depicting Bernie Sanders shaking his fist with the caption “That’s an outrage” leans outside the club). And the Lower East Side venue attracts a truly bizarre and eclectic crowd of nouveau Club Kids, middle-aged men in khaki slacks, bikers, drag queens, Goths and crust punks.

“I want this to be a place where artists come to meet other artists and make a family. I used to have a family,” Alig says. “I had this experience where three of my friends, Edith Pop, Max Skaff of Uncle Meg and Haley Dahl of the Sloppy Jane band, who are singers in the club scene, were all at Outrage. They didn’t know each other. Twenty years ago they would have all been friends and working creatively together. So the fact that they didn’t know each other really freaked me out. Now this party is where they come to meet and exchange ideas. I want more of that.”

Amanda Lepore and Alig at Club USA in New York City, May 1, 1993.

Having spent decades battling drug addiction and the tedium of prison, Alig’s perspective is more introspective. He is working on his memoir “Aligula,” a coffee table book of nightclub invitations and also a sociological work on the Club Kids.

“It places us into context with the punks and yuppies, because Club Kids were really a combination of the two,” he says. “We were also a reaction to that AIDS crisis; a lot of people don’t know that.”

“You have to remember that New York in the mid-’80s was ground zero for the AIDS epidemic. Fear and hysteria were what drove us,” St. James said in a 2014 interview. “There was a prevailing sense that you and your friends might not be around this time next week — so enjoy the now! Don’t think about tomorrow. So we partied too hard, drank too much, laughed too loud. We danced on the lip of the volcano, so to speak.”

Alig paints, a hobby he picked up in prison, and boasts several successful gallery shows in New York and Los Angeles. He says Manson recently bought a piece depicting Mickey Mouse atop a swastika. He’s working on a fashion line that features prints of celebrities’ faces on STD viruses.

“When you think about some of the things I have done in the past and the one big thing, the elephant in the room, it’s weird that I am sitting here at all. I think I have been very fortunate,” Alig says.

Fortunate or not, Alig’s return to New York hasn’t been smooth. He was recently arrested for being in a park after hours in the Bronx, allegedly in possession of meth. His close companion and frequent roommate Keoki was arrested on drug charges this year after a man was found dead, having overdosed on drugs, in an Upper East Side apartment. The New York Post reported that meth, hundreds of ecstasy pills, cocaine, marijuana, 58 green diazepam pills, 56 unidentified pills and $26,985 in cash were found by police in the apartment.

Headlines like “Convict Clubber Michael Alig’s Comeback Is Crashing” and “Club Kid Killer Michael Alig’s Return to NYC Nightlife Not Going So Well” have haunted his homecoming. Social media commenters have ganged up to loudly condemn his nosedive into the very lifestyle that led to Angel’s death. Many of his old friends have either moved on or lamented his return to the scene.

“I’m not exactly sure what [Alig] should do, but I know what he shouldn’t do, and party promoting is at the very top of that list,” Musto recently told Rolling Stone.

Meanwhile, Alig has struggled to put down roots. He currently resides in Paterson, N.J., where he says a young real estate heir who owns “half of Paterson” put him up in a new, four-bedroom loft. Apparently, his benefactor’s favorite movie is “Party Monster,” and he hopes Alig and his friends will create a “new East Village” in Paterson and improve real estate values.

But only recently Alig was floating between what he claimed were suicidal roommates and a crash pad in East New York.

Meeting him was a challenge. Our first three attempts to meet Alig failed.

“Oh. My. Fucking. God,” he texted after Keoki, who was sporting a dyed blue goatee, turned us away from their basement apartment in East New York, where we had scheduled an interview. “I’m so mad at him [Keoki]. He will do anything to avoid responsibility … but God help anyone who interferes with him while in the DJ booth.”

But Alig says he doesn’t mind bouncing around the fringes of New York. He likes frontiers. He says frontiers are where you find inspiration.

“The trend is to say New York isn’t what it was. But nothing is what it was 20 years later,” he says. “That is the whole point. They say it’s over, but for young kids coming out now, New York is still the exciting place to go.”

Alig has said that he feels responsible for his role in associating the underground party scene with extreme vice. Angel’s death helped tip public support against clubs in the vein of the Limelight, Danceteria and the Tunnel. Now part of his repentance to the city is rebuilding an avant-garde party scene.

“My parties have always been artistic statements, and they have always been reflections of the times. Even [the Limelight’s] Disco 2000 turned out to be incredibly prescient because it foreshadowed” today’s gender fluidity, he says.

While he’s still eager to shock, Alig argues that the antidote to late-night ennui and social lethargy isn’t more irony, more kitsch. He advocates for authenticity in the arts — something he thinks all of Western civilization sorely lacks.

“We’ve done miniskirts and maxi-skirts. We’ve done bell-bottoms and peg legs and everything in between. We’ve done glossy and matte makeup. There is just only so many times you can recycle [ideas],” he says. “Humankind is going to move beyond these superficial things toward more enlightened, spiritual things. I think now is the beginning of that.”