What was once a pantheon of Chinese investors is beginning to more resemble a trauma ward.

In April, HNA Group was the belle of the New York ball. Banks were fighting over a chance to finance the Chinese conglomerate’s $2.2 billion acquisition of 245 Park Avenue, according to a source close to the discussions. HNA ended up getting a $1.75 billion mortgage from a consortium led by JPMorgan Chase at a loan-to-value ratio of almost 80 percent. The terms, well above the industry average of 65 to 75 percent, were seen as a vote of confidence in the borrower.

Things look quite different now. Bank of America has told its investment bankers to stop doing business with HNA amid worries over its debt burden and opaque ownership. The company’s monthly debt payments are higher than its revenues, and it’s considering selling assets to pay off loans, Bloomberg reported last month. Bottomless pockets? Not so much.

And consider Anbang Insurance Group, which paid $1.95 billion for the Waldorf Astoria hotel in 2015. In June, the chairman of the company, Wu Xiaohui, stepped away from his responsibilies amid reports that he had been detained by Chinese authorities. Dalian Wanda, one of China’s largest development firms, has reportedly been selling properties to pay off debt and is stepping away from its Los Angeles megaproject, One Beverly Hills. In September Standard & Poor’s lowered the developer’s bond rating to junk, noting that it “lacks strategic clarity and predictability.”

Fosun International, which owns 28 Liberty Street, also got S&P’s junk rating. All four firms are reportedly in the crosshairs of Chinese regulators for taking on too much debt.

For New York’s real estate industry, this should lead to some soul-searching. As Manhattan commercial property values kept climbing in recent years and skeptics started worrying about a bubble, developers and brokers would point to supposedly low leverage ratios as a cushion. If buyers aren’t binging on debt, went the argument, property prices would hold. Now we’re starting to learn that the first part of that argument doesn’t entirely hold up – at least as far as some of the biggest Chinese investors are concerned.

HNA and Anbang may not have funded their New York acquisitions with crazy mortgages, but that doesn’t mean their leverage was low. It was just well-hidden.

Anbang, for example, may have invested plenty of its own cash into the Waldorf Astoria deal and the $6.5 billion acquisition of Strategic Hotels & Resorts in 2016. But much of its equity reportedly comes from the sale of short-term, high-yield insurance policies in China — de-facto a type of risky loan. Now that Chinese regulators are trying to curtail that kind of activity, dealmaking has all but frozen up, and many firms are scrambling to sell assets.

That kind of urgency can be costly. Dalian Wanda “may be forced to sell its offshore assets at unfavourable prices,” Fitch noted in a recent report, if it doesn’t get government approval to move cash out of China to pay off loans. And HNA’s CEO Adam Tan said last month that “if some sectors are now restricted by government, I will consider selling assets I bought in these sectors.”

That’s bad news for New York’s real estate market. But just how bad is a matter of opinion.

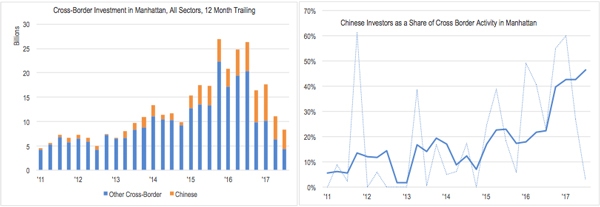

Even at its peak, in the first quarter of 2017, Chinese money accounted for only about 20 percent of Manhattan commercial property sales, said Jim Costello of Real Capital Analytics. If firms like HNA and Anbang leave the market, others may replace them, he said.

“They weren’t the only ones” bidding up prices, he said. “The rest of the market was also being aggressive.”

But it’s also possible that HNA and Anbang had an outsized impact on the market, warping sellers’ expectations by overpaying.

“All the markets price off the top bid and the top bid has been an Asian bid, whether it was the sale of the Waldorf or the bailouts of a Strategic Hotel deal,” Barry Sternlicht said in August. “Everybody thinks they are rich when the guy pays the 2 percent cap for an asset, or a 1 percent cap. If there are six bids at $1 billion and one guy is at $1.5 billion, I would ask you to tell me where the loan-to-value is of the loan, right?”

Sources say HNA’s winning bid for 245 Park, at over $1,200 a foot, was significantly higher than what other bidders were willing to pay. Take away that top bid, and prices fall.

We know that from experience. In the 1980s Japanese investors often overpaid for Manhattan properties. In 1986, for example, Shuwa Corporation bought the ABC headquarters on Sixth Avenue for $175 million, beating out another Japanese bidder. ”There were five other bids, all of them just over or under $100 million,” a broker told the New York Times at the time. When Japanese firms retreated in the early 1990s, the market suffered. Now, history could repeat itself.

Case in point: One Worldwide Plaza. New York REIT put the office tower on the market earlier this year, hoping to fetch $1.7 billion. But offers were disappointing. The reason, according to CEO Wendy Silverstein: all bidders were North American. In the end, the REIT opted to sell a minority interest in the tower.

“If we did this deal in 2014 or 15 foreign buyers probably would have come in and written that large equity check,” Silverstein said during a September earnings call. “We missed the boat with zero foreign buyers in the market.”