Last Tuesday, in between tweets about James Comey, his poll numbers and California, President Trump was at one of his favorite pastimes again: complaining about the U.S. trade deficit.

“Russia and China are playing the Currency Devaluation game as the U.S. keeps raising interest rates,” he tweeted. “Not acceptable!”

For years, Trump has argued that China subsidizes its exports to the U.S. through currency manipulation, creating a trade imbalance (Never mind that the U.S. Treasury disagrees with him). His belief that this trade imbalance is bad for the U.S. and needs to be reversed is one of his few consistent policy positions. In early March, the White House asked China to come up with a plan to reduce its trade surplus with the U.S. by $100 billion. In the following weeks, his administration announced tariffs against a range of Chinese goods. Officially they were in retaliation for intellectual property theft, but as Trump announced the tariffs he tied them to the trade deficit, which he called “out of control.”

Click here to read more of The Long View

The irony is that the U.S. trade deficit has been a huge boon to the real estate industry that made Trump rich.

Whether it’s Japan in the 1980s, Germany in the 2000s or China in recent years, countries that invest heavily in the New York real estate market also tend to have a massive trade surplus with the U.S. And that’s no coincidence. To understand why, here’s a brief detour into the economics of international trade.

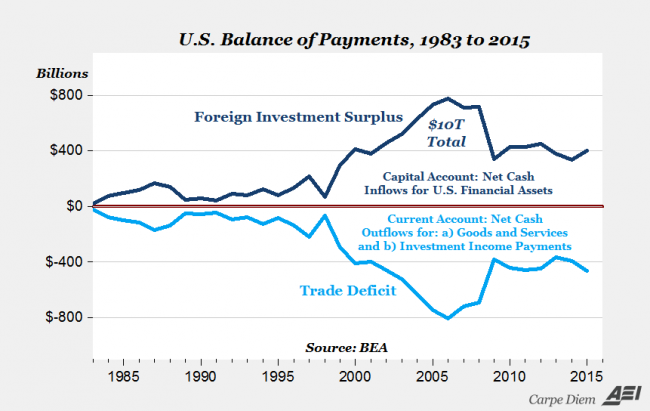

A country has a current account (which includes trade in goods and services) surplus when it exports more than it imports. It can only sustain this if an amount of money equivalent to the surplus flows out in the form of overseas investment. Economists call this a capital account deficit. A persistent current account surplus is always balanced out by a capital account deficit. It’s one of the eternal laws of economics, like gravity in physics.

The chart below, made by think tank American Enterprise Institute, shows how this dynamic played itself out for the U.S. in recent decades.

Countries that export more to the U.S. than they import also tend to pour a lot of money into U.S. assets like stocks, bonds and real estate. Take Japan in the 1980s. As the country grew into an industrial powerhouse and exported more cars and electronic goods into the U.S., it began racking up a huge current account surplus. President Reagan accused the country of cheating, echoing Trump’s arguments of today, and imposed tariffs on some Japanese imports in 1987. But at the same time, Japanese firms poured billions into the Manhattan property market, buying Rockefeller Center, the Empire State Building and several other properties. In recent years, Chinese companies bought up trophy properties like the Waldorf Astoria hotel while its manufacturing firms racked up a trade surplus with the U.S.

This doesn’t mean only countries with a current account surplus will buy U.S. real estate. Canada has been a major investor in the U.S. property market and it’s not clear that the country has a trade surplus with the U.S. It also doesn’t mean that countries with a current surplus will necessarily invest in U.S. real estate. But it does mean foreigners have more dollars to buy U.S. real estate, which makes foreign investment more likely.

“We have every reason to believe that the U.S. trade deficit helps to maintain or raise the prices of real estate in the United States, as well as the prices of financial assets and other assets denominated in Dollars,” said Don Boudreaux, an economist at George Mason University and senior fellow at the Mercatus Center. “And so if Trump somehow really managed to eliminate or dramatically reduce the U.S. trade deficit, one consequence of that could well be a decline of the value of real estate — not only in the New York City area, but throughout the United States.”

Economist and White House aide Peter Navarro has argued that Trump’s economic policies will somehow both reduce the trade deficit and attract foreign investment. But according to Boudreaux, that’s impossible. “This is like fingernails scratching on a chalkboard to me,” he said. “Increasing foreign investment increases the trade deficit. So it’s a logical contradiction.”

It’s unclear how serious Trump is about shrinking the trade deficit, and whether he would even be able to accomplish his goal. China’s trade surplus (excluding services) with the U.S. rose by $28 billion to $375 billion last year, according to a U.S. Treasury report released this month. Reducing it by $100 billion would be a massive undertaking, and it’s made harder by the recent federal tax reform. Debt-financed tax cuts may well push up interest rates in the U.S., which attracts more foreign investment, which raises the value of the dollar, which makes exports less competitive and imports cheaper, which increases the trade deficit.

Still, the Trump administration’s decision to impose tariffs indicates that it is serious about turning decades of U.S. trade policy on its head, and that it might be willing to risk a trade war to get what it wants. When Trump announced the tariffs in March, he said the move would be the “first of many.” That should give New York’s real estate industry plenty to worry about. A scenario in which the U.S. and China end up in a trade war that wrecks the U.S. economy, shrinks foreign investment and sends property values on a tailspin is still unlikely, but no longer outlandish. “Here’s a really effective way to reduce the trade deficit,” Boudreaux said: “Make America a horrible place to invest in.”