New York City hotel developers are about to lose nearly half of the land they can build on as-of-right.

On Wednesday, New York’s City Planning Commission is expected to pass a zoning amendment to require special permits for the construction of hotels in most light manufacturing (M1) zoning districts. After CPC approval, City Council will vote to provide final approval within 50 days. Hotel developers are already treating the outcome of the vote as a foregone conclusion, and acting accordingly.

Officially a part of the de Blasio administration’s action plan to revive manufacturing in New York City, the measure is widely believed to be the result of union lobbying to stem the tide of non-union hotels.

The scope of the zoning amendment is striking: Numbers provided by the Department of City Planning show that land available for as-of-right hotel construction citywide will be reduced by 45 percent. In a detailed point-by-point response submitted to the DCP in July, architect Gene Kaufman argued that this “raises the question […] as to why such a drastic action is proposed, affecting more NYC land than any rezoning in recent memory.”

To better explain the context around this wide-reaching zoning change, The Real Deal analyzed data from the Department of City Planning, the Department of Buildings, and other sources. Here are some of the key facts to know about this controversial rezoning:

How much land are we talking here?

490 million square feet – Current land area available for as-of-right hotel construction in NYC

270 million square feet – As-of-right land area remaining after the zoning amendment

(source: the Final Scope of Work for the M1 Zoning Amendment, pages 50 and 60)

Barred from residential and medium-to-heavy manufacturing zones, hotels have historically been built mainly in commercial districts, and in light manufacturing zones to a lesser extent. The M1 zoning amendment would revoke as-of-right construction for most M1 areas, with the exception of areas near airports as well as “paired” and mixed-use districts, like one section in Long Island City. There will also be an exemption for hotels “operated for a public purpose” – mainly as homeless shelters.

Where are these hotels located?

15% – Percentage of all NYC hotel rooms located in M1 districts

35% – Percentage of hotel rooms located in M1 districts, among projects started since 2010

(source: analysis of Department of Buildings permitting records)

The hotel development boom of recent years has shown a clear tendency towards increased usage of M1 districts. This has been particularly true of the outer boroughs, where 45% of hotel rooms that started construction this decade have been in manufacturing zones.

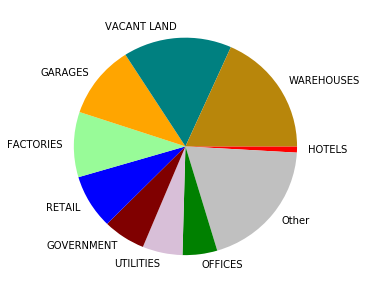

Who occupies the land?

18% – Percentage of M1 land occupied by warehouses

16% – Percentage of M1 land which is vacant

10% – Percentage of M1 land being used for manufacturing

<1% – Percentage of M1 land occupied by hotels

(source: analysis of land use data provided by the Department of City Planning)

Despite the name, not much of the land in light manufacturing districts is really being used for manufacturing these days. About 10 percent of M1 land is occupied by factories and industrial uses, less than garages, warehouses, or even vacant land.

Then again, the amount of M1 land being used by hotels is far smaller still, at less than 1 percent. Critics of the amendment point to these proportions as one key argument against it – can hotels really be to blame for the decline of manufacturing in New York City?

How do these hotels fit with their surroundings?

2.1 – The average floor count of non-hotel buildings in M1 districts

8.8 – The average floor count of hotels in M1 districts

(source: analysis of land use data provided by the Department of City Planning)

At the same time, hotels are the tallest type of building to be found in M1 areas, on average. For supporters of the zoning amendment, this stark height difference is one source of “conflict with neighborhood character” that the special permit is designed to fix.

Could this really be the biggest amendment ever?

136 million square feet – Total lot area of largest zoning map amendment on record

(source: analysis of zoning map amendment data joined with land use data, both from DCP)

The largest changes to the city’s zoning map have tended to be in outlying areas of the city, such as Staten Island, Throg’s Neck in the Bronx or Whitestone and the Rockaways in Queens. And the 220-million-square-foot scope of the M1 Zoning Amendment surpasses them all by far.

But the M1 Zoning Amendment isn’t a change to the zoning map at all – only to the text. It’s harder to compare the sizes of text resolutions, or to say that the M1 Zoning Amendment is truly “the biggest.” It’s true that most text amendments are locally-focused, but there have also been many text amendments with city-wide impact. Mandatory Inclusionary Housing was implemented as a zoning amendment, and arguably impacted large swathes of city land. Zoning amendments regarding floor space calculation and street tree planting clearly also had effects all over the city.

What about IBZs – the original target of the amendment?

360 million square feet – Total land area (minus airports) of the city’s 21 Industrial Business Zones

120 million square feet – M1 land area contained in IBZs

(source: analysis of IBZ lot listings from NYCEDC, joined with land use data from DCP)

Just last year, the city adopted another text amendment requiring special permits in manufacturing areas, to implement another piece of de Blasio’s industrial action plan. Specifically, this amendment required special permits for the construction of self-storage spaces in Industrial Business Zones unless they satisfied certain criteria.

IBZs were first introduced in 2006 and expanded over the years, so that there are now 21 IBZs in the four outer boroughs, totaling over 360 million square feet, excluding airport land. This means the self-storage special permit technically affected more land area than the hotel special permit will – though hotels are certainly a more high-profile building class than mini-storage warehouse.

Originally, the hotel special permit was also envisioned to apply to IBZs only. Unlike storage facilities, hotels are already excluded from nearly two-thirds of IBZ land (M2 and M3 districts) anyway, so the impact would have been limited to the 120 million square feet of IBZ M1 land. These would have been the areas where a concern about hotel encroachment on industrial use was most justified.

At some point, however, the scope of the original hotel special permit plan was expanded to cover nearly all M1 districts, rather than just the IBZs – thus nearly doubling the amount of land covered by the amendment. This decision has drawn criticism from opponents, who argue that it is now too broad and fails to distinguish between the very different characteristics of M1-6 zones in Manhattan and M1-1 zones in the outer boroughs.

Would anyone file for special permits?

12 million square feet – Land area currently requiring special permits for hotel construction

0 – Number of applications filed for hotel special permits

(source: DCP Final Scope of Work, page 50; and the DCP’s land use application search tool)

Proponents of the hotel special permit are eager to emphasize that it is a special permit, and not an outright ban. What could be wrong with taking a more careful, considered approach to the development of the built environment? However, the history of previous hotel special permit rezonings tells a different story.

Hotel special permit provisions have previously been introduced in specific areas such as Tribeca (2010), Hudson Square (2013) and East Harlem (2017), to name a few. And the total number of applications filed for special permits in all of these areas is zero. The extra cost, time and uncertainty that a special permit process entails appears to have been enough to discourage hotel developers from building in special-permit zones entirely.

For its part, the DCP says in its Final Scope of Work that “the lack of applications for those existing hotel special permits may not be relevant to this case.”

What happens to the pipeline?

38,000 – Hotel rooms in pipeline at the time the DCP’s Final Scope of Work was written, in 2017

28,100 – Projected unmet demand for hotel rooms in 2028, according to the Final Scope of Work

(source: DCP Final Scope of Work, page 53)

This set of numbers from the DCP report has amazing implications, if true. The first number – 38,000 rooms in the pipeline – lines up quite well with a previous TRD analysis. But when combined with the second number – which says that only 28,000 more rooms are needed to satisfy hotel demand for the next decade – this means that not only will no more new hotel projects enter the pipeline in the next 10 years, but a solid 10,000 rooms currently in the pipeline are unlikely to be completed.

The DCP says as much in its own words: “It is projected that only a portion of the hotel rooms currently in the pipeline would actually be completed by the 2028 build year. Accordingly, it is expected that the projected lower demand for additional hotel rooms by 2028 would result in developers considering new projects as a high-risk investment.”

Opponents of the amendment have criticized these projections from two angles. Firstly, they argue that the projection is clearly incorrect and far too low, undermining the reliability of the entire report and the justification for the special permit. And secondly, if the DCP does indeed believe that hardly any hotel projects are likely to be started in the next ten years, it has very little reason to go through the trouble of creating a special permit to limit something that isn’t going to happen anyway.

How did the unions do it?

35,000 – Number of Hotel Trades Council members in New York

55,000 – Total number of hotel industry employees in NYC

(sources: HTC website and Census Bureau County Business Patterns, 2016)

With approximately 35,000 members in New York State and northern New Jersey, the New York Hotel and Motel Trades Council isn’t a particularly large union, but it has become known for punching above its weight thanks to a sophisticated ground game and strategic vision. Its influence convinced the Hotel Association of New York City to sit on the sidelines.

Some opponents of the union have downplayed its role in the New York hotel industry. For example, a number cited in Kaufman’s response to the DCP says that the HTC’s market share is currently “under 10%”. But at least according to Census Bureau statistics on hotel employment in NYC, the Council’s own estimate that it represents “approximately 75 percent of the hotel industry within the five boroughs of New York City” appears reasonable.

Why would the union support this?

197 – The number of union hotels in NYC

over 700 – The number of hotels in NYC

(sources: HTC’s “Union Hotel Guide” and DCP land use data)

Despite representing nearly three quarters of hotel workers in the city, HTC has only unionized less than a third of New York’s hotels – with new outer borough and M1 hotels being its Achilles’ heel in particular. Outside of the 190 HTC-recognized “union hotels” in Manhattan, HTC has a presence at just three hotels in Brooklyn and four in Queens, none of which are in M1 areas. The gap between employee share and hotel share implies that the average union hotel employs significantly more staff than a non-union hotel.

According to a TRD analysis cross-referencing DOB data with HTC’s union hotel list, only five out of the 120 hotels completed since 2013 currently have union contracts. The hotel boom has been outpacing union efforts for some time, and from the HTC’s point of view, it would make sense to support measures to limit new hotel construction.

At a political meeting in 2015, HTC president Peter Ward listed Airbnb, non-union hotels, and the decline of the Euro as the three major problems facing the union. “We can’t do anything about the Euro, but we can do plenty about the other two things!” he said at the time.

“It is a goal of the union to have a law passed where hotels in certain areas can only be built with special permits,” he added.