Trending

Glenwood’s return: Luxe developer and political kingmaker breaks into affordable housing

With the Silver and Skelos corruption trials finally behind it, Glenwood Management is cutting new deals and writing more election checks

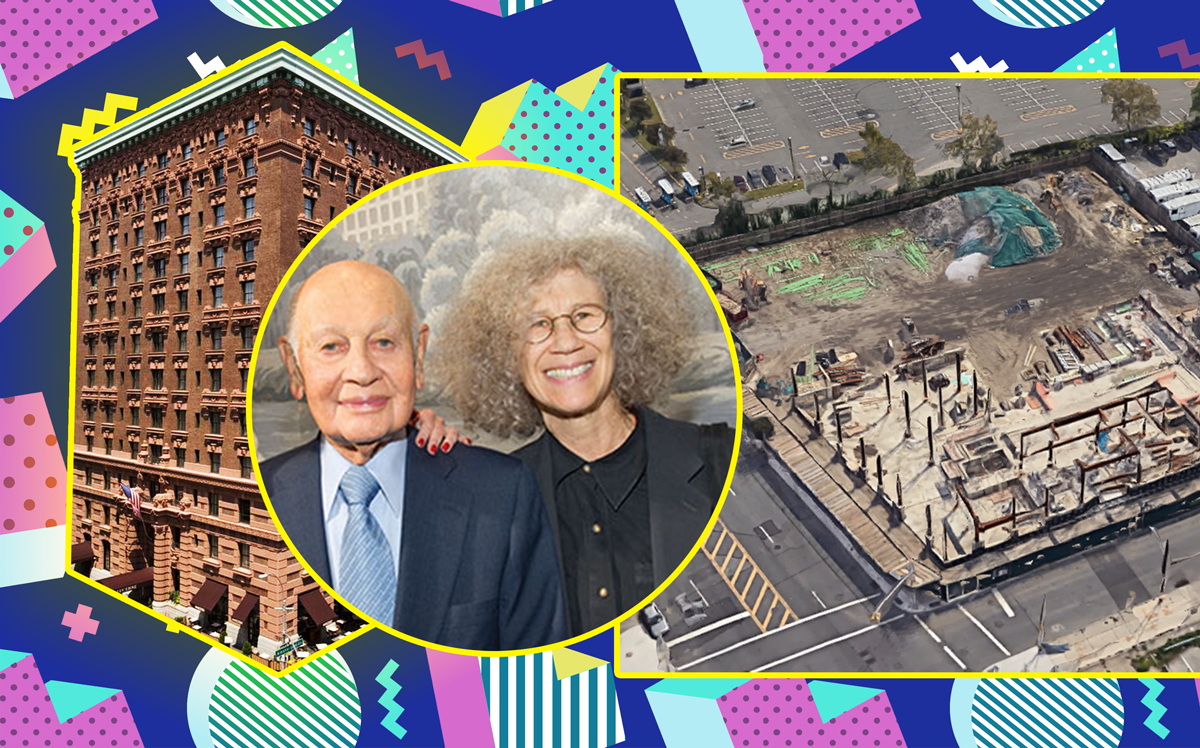

When Leonard Litwin died at the age of 102 last April, he left behind more than two dozen luxury apartment buildings in Manhattan and the longest campaign contribution paper trail in the history of New York State.

Since then, Litwin’s Glenwood Management, now controlled by his 71-year-old daughter Carole Pittelman, has taken an unexpected course: the developer is pushing into affordable housing in Coney Island, working as a construction contractor under the name “Surf Avenue Construction, LLC.”

The change is news to some who have done business with Glenwood over the years, including one investment-sales broker who recently spoke to company executive Gary Jacob.

“I’m surprised to hear of them doing an affordable deal,” said the broker, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “They’ve never done that. It’s the first one as far as I know.”

Meanwhile, Glenwood’s core business, the luxury residential towers that line the tony avenues of the Upper East Side, isn’t set to change, so long as Litwin’s heirs respect his final wishes. According to Litwin’s will, obtained by The Real Deal from Palm Beach County, Florida probate court, the heirs ought to “avoid” selling any of his buildings.

As Glenwood enters the government-reliant affordable-housing business, the developer’s formerly prolific campaign contributions are also back on the rise. Although they dropped dramatically following the 2015 indictments of state legislators Dean Skelos and Sheldon Silver, who were both accused of taking bribes or kickbacks from Glenwood, a large surge in donations since the period between the indictments and Litwin’s death would suggest they’ve gotten over it.

Representatives for Glenwood declined to comment for this story.

The famed Luna Park on Coney Island reopened in 2010 after being shuttered for decades.

Coney Island attraction

“It took a couple of weeks of round the-clock scrambling by construction crews, but… the famously-named Luna Park in Coney Island did in fact open its gates to the public the past Memorial Day weekend.”

So opens a blog post from 2010 on Glenwood’s website in 2010. Curious timing, as there were no Glenwood properties anywhere near South Brooklyn, or in Brooklyn at all. Similar posts on the website would follow in 2011 and 2012.

The reason for Glenwood’s interest in a three-acre amusement park is difficult to discern, but by 2015 references to “Coney Island West” began popping up in Glenwood’s state lobbying reports. Now, the Glenwood affiliate, Surf Avenue Construction, is the general contractor for the five-phase veterans’ housing project known as Surf Vets Place just down the street, according to Christine Velia of the Concern for Independent Living, the nonprofit group developing the building alongside Georgica Green Ventures. David Gallo, Georgica’s president, declined to comment.

The Surf Vets Place complex is centered at 3003 West 21st Street, and the first building is slated to stand nine stories tall with 53 affordable housing units, 82 studio apartments for homeless veterans and 7,000 square feet of retail space. In an interview, Velia estimated that the first building is about 85 percent complete. The next building will rise at 2006 Surf Avenue. That 20-story rental will span about 190,000 square feet with 216 residential units. Permits were filed earlier this year and suggested the real estate investment trust iStar was involved, but the company recently sold its stake to Georgica and New Destiny Housing, property records show.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration rezoned this area of Coney Island in 2009, paving the way for a growing number of new development projects. Other developers taking advantage include John Catsimatidis’ Red Apple Group and Rubin Schron’s Cammeby’s International.

Glenwood, which specializes in high-end doorman buildings with port-cochère driveways and large chandeliers hanging in the lobby, will not be involved in managing the Coney Island affordable buildings, Velia said. But their move into affordable housing is logical, real estate executives said.

Joy Construction’s Eli Weiss, a developer who has built several affordable-housing projects, noted that Glenwood has experience with affordable housing from developing “80-20” rental buildings in Manhattan. The developer’s deep knowledge of how New York government works positions it well to tackle all-affordable projects, he said.

“They understand tax credits,” Weiss said. “They understand tax-exempt bond financing. They understand tax abatements, and they understand working with various government agencies.”

Official minutes from a New York State Housing Finance Agency meeting in August 2016 show up to $37 million in state bonds have been approved for the project and mention the involvement of Surf Avenue Construction.

It’s not clear when or why Glenwood first decided to get in on Coney Island’s development renaissance. But 2010, the year Luna Park content starts appearing on the company website, is also the same year that Pittelman, who was long involved in Glenwood’s construction division, estimates that she took a greater role in directing the company’s overall operations, according to a 2016 court deposition.

“Equal love and affection”

The notoriously press-shy Litwin reached number 364 on Forbes’ list of the wealthiest Americans in 2006, with a total net worth estimated at $1 billion.

Litwin’s will, written in 2013, states that after his death, Pittelman would control all of his shares in Glenwood and would become the trustee of his “Manhattan Realty Trusts.”

Pittelman and her sister, Diane Miller, are supposed to share income from those trusts equally, however.

“Let me state that which should be known to all members of my family,” Litwin wrote. “While I have named Carole the executor of my will and the trustee of the trusts established under my will… I have equal love for Diane and Carole.”

In the will, Litwin included specific instructions about what should not be done with his remaining holdings. For example, in one all-caps paragraph, Litwin hopes trustees “AVOID THE NEED TO SELL” Glenwood buildings, and wishes that except for Pittelman, all other trustees, including Glenwood executive Charlie Dorego as a successor trustee, be prohibited from starting new construction projects, investing in any new real estate or even creating any new limited liability companies. The company has already sold one rental building since the will was written, albeit while Litwin was still alive. In 2016, it sold the Hamilton at 1735 York Avenue to Charles Dayan’s Bonjour Capital for $150 million.

While details about the total value of Litwin’s estate are not given in the will, one provision details how both Pittelman and Miller are to each receive up to $4 million in annual income from their stakes in just one rental building, The Paramount at 240 East 39th Street. (Both daughters’ total trust allowances are capped at this $4 million number annually, according to the will.) Each of Litwin’s four grandchildren, including developers Steven and Howard Swarzman, will make $2 million a year from the trusts, according to the will.

When he took over Glenwood from his father in the 1960s, Litwin flirted with co-op construction before almost exclusively building high-end rental towers for the next four decades, first on the Upper East Side of Manhattan but later expanding to Midtown, Downtown and the Upper West Side. In 2013, Glenwood announced its first condominium project, a 15-unit building at 60 East 86th Street. Litwin’s grandsons made that call, according to the New York Times, because of high land prices. One real estate executive familiar with Glenwood’s current operations told TRD that Glenwood remains on the lookout for rental development sites. But land prices are still too high for its tastes, another reason the company may look toward affordable housing.

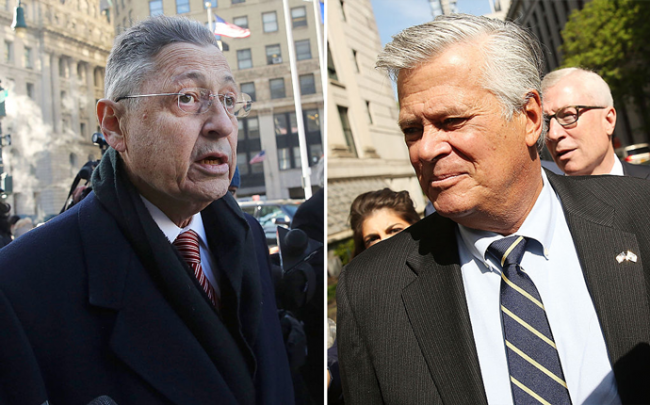

Sheldon Silver and Dean Skelos (Credit: Getty Images)

Tip for good service

On a single day, July 11, 2014, Glenwood gave $400,000 to state campaign committees through LLCs tied to the company’s Manhattan holdings. Common Cause, a nonprofit watchdog organization, found that Glenwood spent $13 million on state elections in the decade between 2005 and 2014, more than any other donor.

But the 2015 indictments of Albany’s most powerful legislators, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos, changed the political calculus of these gifts, at least temporarily.

In the Silver case, the Speaker was accused of accepting kickbacks from a law firm Silver had asked Glenwood to give its property-tax business. And in the Skelos case, prosecutors accused the majority leader of asking Glenwood for favors, including business contracts for his son, Adam Skelos. Dorego cooperated with federal prosecutors, and neither Glenwood nor its executives were indicted in connection with either case. Silver, Skelos and Adam were later convicted, and after retrials this year, were convicted again.

Glenwood’s long history of campaign donations and its regular lobbying on rent laws and the 421a developer tax exemption (which it continues to benefit from) were major themes of the court proceedings.

One New York developer, speaking on condition of anonymity, suggested that the corruption trials could have motivated Glenwood to take on affordable-housing projects.

“There was a period of time with the whole Sheldon Silver thing where their name was being dragged through the mud,” he said.

In the immediate aftermath of the indictments, Glenwood cut back significantly on both political contributions and lobbying activity, a TRD analysis of state elections records shows. Through the 26 months between the February 2015 indictment of Silver and Litwin’s death in April of 2017, Glenwood gave just $115,000 to state political committees.

These days, Glenwood looks a little more like its old self again, at least when it comes to political spending.

Since Litwin’s death 18 months ago, Glenwood’s LLCs and executives have contributed at least $363,850 to state committees, more than three times what they spent in the previous two years. That bump is perhaps due in part to the 2018 gubernatorial election, though Glenwood is no longer giving to Gov. Andrew Cuomo directly and is instead directing most of its dollars to accounts affiliated with the Rent Stabilization Association and the Real Estate Board of New York.

The handful of politicians who have taken Glenwood’s money directly over the last year include state senators David Carlucci, Tim Kennedy and Brian Benjamin, state attorney general candidate Sean Patrick Maloney and state senate candidate Aaron Gladd, all Democrats.

Company lobbying activity has not returned to its 2014 levels, however. And by January of 2016, Glenwood had cut its roster of registered lobbying firms from seven to one, according to state lobbying records. Robert Bishop, a founding partner at the Pitta Bishop Del Giorno & Giblin lobbying firm, did not respond to a request for comment.

John Keahny, director of the government-accountability group Reinvent Albany and a critic of New York’s campaign finance laws, suggested Glenwood got off lightly with the $200,000 lobbying violation it was handed by the Joint Committee on Public Ethics in 2016. As part of the fine, Glenwood admitted to violating the Lobbying Act in actions it took with both Silver and Skelos and admitted doing so “out of concern that losing the support and influence of the then-powerful lawmakers would harm its business interests,” according to a JCOPE press release.

“How many times does a company have to be implicated in bribery schemes to be considered engaged in racketeering and corrupt practices?” Keahny said.

Betsy Gotbaum, executive director of the good government group Citizens Union who was New York City Public Advocate between 2002 and 2009, said Glenwood’s uptick in donations again was concerning. But she placed the blame more on the state’s campaign finance laws than on Glenwood itself.

“If it’s legal,” Gotbaum said, “there’s nothing we can do about it.”