“Do I love it? No. But can I live with it? Yes.”

New York City’s ultra-wealthy buyers dodged a bullet last week when lawmakers abandoned a proposed pied-à-terre tax on luxury pads. But some brokers now fear everyday buyers will bear the brunt of a progressive mansion tax that took its place.

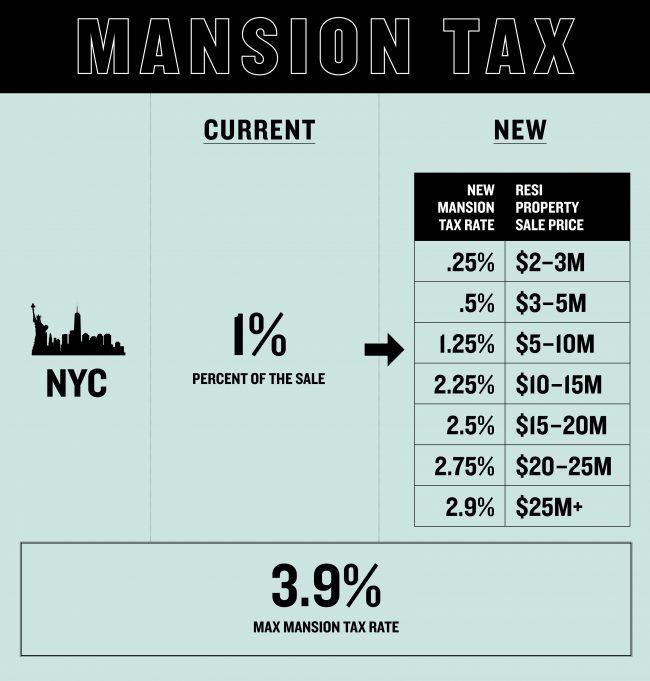

The new mansion tax will start at 1.25 percent on sales above $2 million but under $3 million; the tax tops out at 3.9 percent for sales above $25 million, according to the state’s new budget. (The existing 1 percent mansion tax is baked into those figures.)

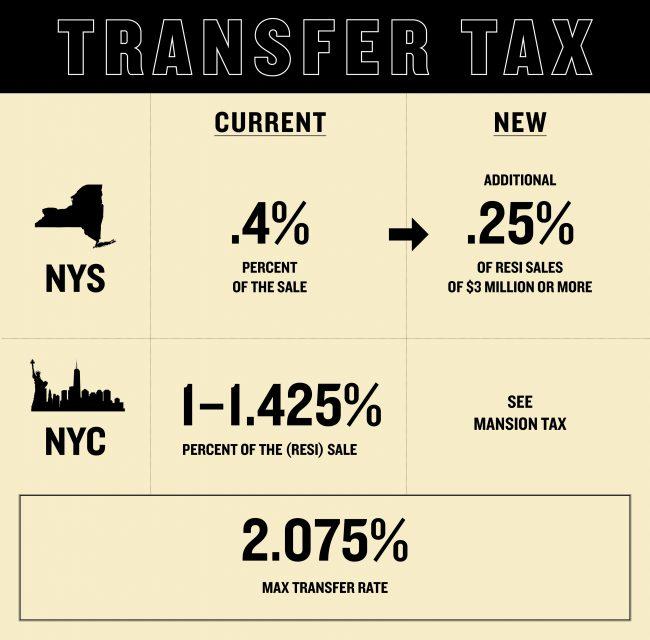

Combined with a progressive transfer tax, the assessments are expected to generate $365 million in revenue.

But Compass’ Leonard Steinberg — a vocal critic of the pied-à-terre tax — said the mansion tax is a “dirty means of raising taxes at the expense of a class of people lumped under one umbrella.” In fact, he argued, buyers spending $3 million have vastly different finances than those who can afford $25 million or more.

“What’s pretty unbelievable is the only message that has been broadcast from Albany is that people who buy $25 million and more will be paying,” he said. “There’s been very little mention that everyone between $2 million and $25 million will be paying more taxes, as well.”

Several other agents expressed concern that sales under $3 million would slow if buyers had to factor in the cost of additional taxes.

“These buyers, in most cases, are financing their purchase and are on pretty tight budgets,” said Warburg Realty’s Sheila Trichter. “It seems that these tax increases are once again hurting the middle class and helping the 1 percent.”

But broad swaths of the industry, which vehemently opposed an annual pied-à-terre tax, said the new mansion tax is the lesser of two evils.

Although proponents said the pied-à-terre tax would have raised $650 million in tax revenue each year, an industry-backed analysis said the figure was close to $372 million. Real estate players also cited the legal and logistical problems with enacting a tax based on the city’s arcane property assessment system.

A one-time, point-of-sale payment is far more straightforward.

“It’s digestible,” said Bess Freedman, CEO of Brown Harris Stevens. “Do I love it? No. But can I live with it? Yes.” She said the new mansion tax will give the state the revenue it needs without deterring buyers from purchasing in New York. “It may have an impact, for sure, but not the way the pied-à-terre tax would have run us over.”

In the weeks leading up to the budget, real estate players including developer William Zeckendorf — a co-owner of BHS’ parent company, Terra Holdings — lobbied furiously against the pied-à-terre tax. On March 25, elected officials shifted their focus to a one-time transfer tax for luxury real estate.

In a statement after the budget decision, REBNY President John Banks acknowledged that “hundreds of millions” of dollars will now flow from the real estate industry to state coffers to support transit improvements. “It is now critically important that such funds be deployed in the most effective manner possible,” he said, urging lawmakers to continue to monitor the impact of new tax policies.

“Look, it’s not good but it’s better than the pied-à-terre tax, which was ill-conceived and based on numbers out of thin air,” said Donna Olshan, founder of Olshan Realty, which tracks luxury sales.

By applying the new tax rates to Manhattan sales in 2018, Olshan estimated the new taxes would generate $274.6 million in new revenue from residential sales in the borough.

Buyers in the $5 million to under $10 million segment will be shouldering the biggest portion of the new mansion taxes — based on 637 deals in that price segment last year, Olshan’s figures show. With an average price of $6.8 million, buyers in that segment would owe $97.97 million, up 125 percent from $43 million.

The new tax structure — which goes into effect July 1 — also imposes a progressive transfer tax of .25 percent for residential pads above $3 million and commercial properties above $2 million, according to the state budget. That money will be deposited into a “capital lockbox” to support up to $5 billion in transit projects.

“Essentially what they’re doing is they’re widening the footprint over the market, but they’re making it less draconian for a smaller segment,” said appraiser Jonathan Miller. He was another vocal critic of the pied-à-terre tax proposal, which he argued would result in lower tax revenue because sales volume and values would have dropped.

As it is, the luxury market has taken a beating over the past year. Manhattan luxury sales volume has dropped for five consecutive quarters, according to data from Miller Samuel. During 2018’s fourth quarter, luxury sales declined 3.2 percent year over year to 244.

But brokers said things have started to pick up over the past month, as sellers adjust their prices to keep the market moving. And now it won’t have the pied-à-terre tax to content with.

“It’s been a tougher market, but we’re in a good place,” BHS’ Freedman said. “Deals are happening.”