In the sales pitch for 110 Wall Street, brokers for Rudin Management gave voice to landlords’ worst-case scenario involving WeWork: default.

An offering memo circulated in recent months by brokerage Eastdil Secured cited the possibility that the co-working giant — Rudin’s sole tenant at the 27-story Financial District office building — would live up to critics’ expectations and fail to pay its rent if the economy turns.

“Given the single-tenant nature of 110 Wall Street, the outcomes of the asset are binary,” said the memo, a copy of which was reviewed by The Real Deal.

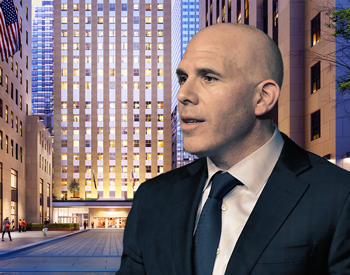

Bill Rudin said the decision not to sell had nothing to do WeWork, but rather an internal conclusion that the company did not need to sell the property. “It’s a great asset,” he said.

Rudin, who met WeWork co-founder Adam Neumann at a cocktail party in 2012, recalled being blown away with an earlier iteration of the company’s shared offices. A month later, in the wake of Sandy, he recalled crawling through a debris-strewn 110 Wall with Neumann.

For Rudin, there was a question of tearing down the building or saving it — and fast. “We were taking a chance on WeWork back then, we were spending significant capital and needed to protect ourselves,” Rudin said. But he insisted that’s standard business practice. “Everyone tries to protect their downside, even with Triple A companies you have corporate guarantees.”

The overarching goal, Rudin added, was to revitalize Downtown after the double-whammy of 9/11 followed a decade later by a devastating storm. “What they’ve done is make everybody up their game in terms of what [landlords] need to do to attract and retain tenant in terms of infrastructure, amenities and quality of the building,” he said. “It’s a different world today. You have to be that much more competitive and that much more attentive to what your clients need.”

But to some, the sales pitch for 110 Wall offers a commentary on landlord confidence in the $47 billion SoftBank-backed firm (which restructured earlier this year, becoming the co-working line of a parent company known as “The We Company”) as it gears up for an IPO, and hints at building owners’ reservations about what will happen to its leases if a recession hits.

“It’s a caveat emptor: ‘Hey, don’t blame us if you buy this thing and you run into trouble,’” said Timothy King, managing partner at CPEX Real Estate, commenting on the sales pitch for 110 Wall. “The landlord is almost at the mercy of WeWork if they’re the single tenant. To some extent, they’re the ones holding the cards.”

According to King, many landlords still consider co-working leases to be an untested business model. “The question I hear most often is, ‘What happens if we through a protracted downturn?’” he said. “A bootstrapping startup that moved from the kitchen table to a shared space is still in an embryonic state and can either flame out overnight or take off like a rocket.”

One commercial brokerage chief, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said that in a downturn having multiple tenants is safer for landlords than having one large tenant that can crash and burn. “The fact is that in some respects, if I own the building and WeWork went out, I might be in a better position,” the brokerage head told The Real Deal.

Landlord blowback

Tony Malkin (Credit: Max Dworkin)

Several New York landlords have resisted leasing large chunks of their buildings to co-working tenants.

One of the most prominent owners to publicly denounce WeWork is Empire State Realty Trust, whose CEO Tony Malkin has said, “We do not, have not and will not lease to WeWork.” Billionaire real estate investor Sam Zell, founder of Equity Group Investments, also has been a longtime skeptic of WeWork’s business model. (“I wouldn’t let those guys near my business with a 10-foot pole,” he said in 2017.)

When they were like, ‘We’re going to people with between one and 10 employees, we were like fine, we don’t do anything that small,’ said one source. Fast forward five years, and here we are chasing 75,000-square-foot users who are with them and that’s annoying.

Meanwhile, last fall the Durst Organization rejected WeWork’s offer to lease up to 12 floors at World Trade Center, saying there were better offers on the table. (Landlords offered a slew of reasons to be wary of co-working tenants: increased wear and tear on the building, a need for extra cleaning for densely-packed offices and high foot traffic in and out of the building.)

Although Durst declined to comment for this article, other landlords have said their own thinking on WeWork evolved after the company began chasing big corporations as tenants. “When they were like, ‘We’re going to people with between one and 10 employees, we were like fine, we don’t do anything that small,’” said one source. “Fast forward five years, and here we are chasing 75,000-square-foot users who are with them and that’s annoying.”

Douglas Durst at One World Trade Center (Credit: Getty Images)

At the same time, some property owners said they prefer WeWork’s enterprise tenants to traditional co-working. RXR Realty, for example, generally doesn’t sign co-working leases in its Class A buildings because the subtenants are so transient. But CEO Scott Rechler said he views WeWork’s enterprise deals differently. “If you think of them as a sales channel of fully curated, one-stop procurement for an end-user,” he said, “I think they can play a good role of filling your buildings and keeping them filled in a collaborative way.”

In May, RXR said WeWork would manage 90,000 square feet at 75 Rockefeller Plaza in a revenue-sharing agreement, the co-working giant’s first such deal in New York. We Company will take four floors in the 32-story tower, where Convene and Airbnb also lease space.

Backing WeWork early and often

Rudin Management — known for holding properties long-term — put 110 Wall up for sale this spring, along with One Whitehall Street, a 21-story office tower asking $200 million. Sources said both were tied to estate planning, following Jack Rudin’s death in 2016.

Rudin declined to discuss the unusual sales pitch, as did representatives for the We Company. But Bill Rudin was an early investor in WeWork, along with Boston Properties’ Mort Zuckerman. Rudin and Boston Properties have also teamed up with WeWork to develop Dock 72 in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The co-working firm is set to occupy 200,000 of the project’s 675,000 square feet.

Dock 72

If Rudin was disappointed in the offers it received, it did not say so. But some brokers said describing WeWork’s possible “default” was a head-scratcher. “You don’t know if it’s perceived risk or actual risk,” said one broker. “If you have two identical buildings and one is 50 percent or 100 percent filled with WeWork and one is multi-tenanted with good credit, they don’t achieve the same cap rate,” the broker said.

Sources close to parent company the We Company and 110 Wall said the FiDi building — which is also home to WeLive — was a “win” for both landlord and tenant. And they said demand for WeWork, which has 485-plus locations and 466,000 members, should instill confidence in any prospective buyer. In that regard, the offering memo simply seeks to reassure would-be investors that the single-tenant building is a valuable asset even if WeWork defaults.

In that scenario, the memo said, the new owner would possess a “highly improved building” with more than $100 million in capital invested since 2014, two years after Superstorm Sandy seriously damaged the property. The “mitigated downside” would also include a letter of credit with two times the rent coverage; mark-to-market opportunity of about 14 percent below market value; and a stellar location in a neighborhood with 5.5 percent average population growth and a low vacancy rate.

According to the memo, if WeWork performs on its lease the new owner will benefit from $210 million in contracted rental income. WeWork has 22 years left on the lease, according to the marketing materials, which also say the co-working firm is subject to 2 percent annual rent increases.

With more than 50 locations in New York City, the We Company claims to be the city’s largest leaseholder. In April, the company quietly filed for an IPO, and it is currently looking to raise several billion dollars by selling debt ahead of the planned public offering, a move that would boost investor confidence. Although WeWork’s revenue doubled last year to $1.8 billion, so did its losses, which topped $1.9 billion.

RXR Realty’s Scott Rechler and 75 Rockerfeller Plaza (Credit: RXR Realty and Getty Images)

Despite critics’ dire predictions of how WeWork will perform in a downturn, co-working has remained a bright spot in the overall office leasing market. Manhattan leasing activity rose 13 percent during the first half of the year to 20.26 million, according to a Colliers International report released this month. Of that, the FIRE (financial services, insurance and real estate) sector accounted for the largest share of leases — 38 percent — with one-third taken by co-working companies. TAMI (technology, advertising, media and information) leases followed with 28 percent.

“Obviously a lot of landlords are very comfortable with [co-working] because WeWork and others are leasing a lot of space,” said Craig Caggiano, an executive director at Colliers. “The sector has been strong over the last few years, and that’s reflective of a healthy market and very healthy job growth.”

For lenders, how much is too much?

But even owners who’ve embraced co-working acknowledge they are treading a fine line when it comes to large co-working leases. “The general sentiment is, what percent of your building could you lease to WeWork — or any flexible office provider — without having a concern in terms of the financeability or impact on sale,” Rechler said.

He said 20 percent to 30 percent is the accepted threshold, depending on the rest of the tenants in the building.

While some banks have shied away from financing buildings with WeWork as a sole tenant, others have made smaller loans to hedge their investments in single-tenant buildings.

Starwood Property Trust’s Jeff DiModica (Credit: Cornell)

During a first-quarter earnings call in May, Starwood Property Trust’s Jeff DiModica discussed the company’s loan to WeWork to fund the purchase of the Lord & Taylor building for $850 million. (Eastdil Secured negotiated the $900 million acquisition loan from JPMorgan Chase, Starwood and an unknown lender.)

“We were very comfortable at 50.5 percent LTV (loan to value),” DiModica said. “If it were in the 70s… a single tenant, like WeWork, might be something that would scare us a bit given our apprehension to take those type of risks.”

Rechler conceded that a recession could have either of two outcomes: subtenants may double down on co-working to avoid capital investments or retreat from co-working spaces in an attempt to cut costs.

Those concerned with the latter scenario said WeWork forms a subsidiary on each lease deal to insulate the parent company if individual locations languish. One broker told TRD he’s seen WeWork leases in which the company only guarantees three years. And a Bloomberg report earlier this year said the company guarantees just six to 12 months on a 15-year agreement, per regulatory filings.

“If you’re going to commit your space for a term of 10 years, you want to make sure that your tenant is credit-worthy and they’re gonna be there tomorrow, the next year and the year after that,” Michael Emory, CEO of Allied Properties REIT, was quoted as saying at the time.

To protect themselves, some landlords have reportedly accepted lower rent from WeWork in lieu of making tenant improvements.

But so far, it’s unclear if a single tenancy by WeWork will impact sales prices.

A study last year by Cushman & Wakefield found that investors apply a discount when pricing office properties where co-working firms, including WeWork, occupy a large portion of the building. “With this new co-working environment, we haven’t yet been through a full office cycle,” David Bitner, Cushman’s head of capital research for the Americas, told TRD last year. He said the market is still jittery over flexible-space provider Regus’ bankruptcy in 2001.

One prominent investment sales broker, who asked to remain anonymous, said it’s because of that uncertainty that Rudin and Eastdil likely decided to mention WeWork’s possible default in the sales pitch for 110 Wall. The broker said it’s not unprecedented to sell a single-tenant building — and in that case, too, a savvy broker or owner would be wise to spell out a downside scenario. This case stands out, however, “because WeWork is so visible,” the broker said. “They act like a credit tenant and they’re not.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated at 1:30 p.m. on Monday to reflect comments by Bill Rudin on why the building was pulled from the market.